(listen)

John Lennon and Paul McCartney were always steadfast in their denial that this was a drug song, a tag that earned it a ban from the BBC and a lot of unwelcome stigma as well. I think it's true that "I'd love to turn you on" and "found my way upstairs and had a smoke / somebody spoke and I went into a dream" are fairly slim reeds on which to hang the charge. On the other hand, the eerie racket that follows those lines is not, particularly. That is some strange stuff, and I still remember the moment I first heard this because of those passages. I was getting up early, before daylight. I was getting dressed. I was putting on a blue and white plaid shirt, buttoning it. It was winter and I was wearing long underwear under my pants. I knew it was the Beatles by the voices and general tenor of it but I didn't know anything else about it. And it scared me badly. I thought something was wrong with my radio and kept fiddling with the tuning and then the song would come back. And then that weird shit would come back. And then the song again. It reminded me of a frightening dream I'd had before, in which I could not make my radio stop playing, even unplugging it from the wall and finally smashing it, only to discover a small person inside it singing. I was basically too young (and/or naive) to understand about drugs, but "A Day in the Life" was profoundly disturbing and unsettling for me. Eventually, perhaps artifact of Stockholm syndrome or something like it, I came to embrace it as basically my one favorite Beatles song. It's got all the tunefulness I loved and came to expect from them, but it really packs a wallop as well, and on multiple levels.

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

18. Bruce Springsteen, "The River" (1980)

(listen)

Bruce Springsteen works best for me in a doleful mood—it's the thing about him that took me awhile to figure out, that finally got me past his fans and my worst contrarian impulses and those early exercises in beatnik poetry and all the hoopla attached to him like skin ink. I arrived as a doubter and left as a believer, late as usual, which I doubt will impress either his skeptics or his most ardent partisans, but there it is. The sad take of "The River" on the state of marriage has always gone to work on me the moment I hear its mournful sounds fading up. It comes from a singer, at least—and a songwriter too, I'm pretty sure—who believes in the institution, and if it's ultimately more about class and the grinding conditions and above all the loss that class imposes than it is about love, it's about love too. It has to be. The loss amounts to more, even to something else entirely from love: youth, hope, wonder, the sense that life holds great things in store for anyone with the opportunity to go skinny-dipping on a warm summer night with one's partner. But it starts and ends with faith in love. I'm still not entirely sure about Springsteen's many first-person songs addressing some anonymous authority figure known only as "mister" (which is to say I'm still not entirely sure about Nebraska), but it works here. As do the concrete details, even when they veer dangerously close to cliché. And as does, more than anything, the critical center of this song, the impossible question we're left to ponder: "Now those memories come back to haunt me / They haunt me like a curse / Is a dream a lie if it don't come true / Or is it something worse?" Answer that one and you get a prize.

Bruce Springsteen works best for me in a doleful mood—it's the thing about him that took me awhile to figure out, that finally got me past his fans and my worst contrarian impulses and those early exercises in beatnik poetry and all the hoopla attached to him like skin ink. I arrived as a doubter and left as a believer, late as usual, which I doubt will impress either his skeptics or his most ardent partisans, but there it is. The sad take of "The River" on the state of marriage has always gone to work on me the moment I hear its mournful sounds fading up. It comes from a singer, at least—and a songwriter too, I'm pretty sure—who believes in the institution, and if it's ultimately more about class and the grinding conditions and above all the loss that class imposes than it is about love, it's about love too. It has to be. The loss amounts to more, even to something else entirely from love: youth, hope, wonder, the sense that life holds great things in store for anyone with the opportunity to go skinny-dipping on a warm summer night with one's partner. But it starts and ends with faith in love. I'm still not entirely sure about Springsteen's many first-person songs addressing some anonymous authority figure known only as "mister" (which is to say I'm still not entirely sure about Nebraska), but it works here. As do the concrete details, even when they veer dangerously close to cliché. And as does, more than anything, the critical center of this song, the impossible question we're left to ponder: "Now those memories come back to haunt me / They haunt me like a curse / Is a dream a lie if it don't come true / Or is it something worse?" Answer that one and you get a prize.

Monday, November 28, 2011

19. Bob Dylan, "Ballad of a Thin Man" (1965)

(listen)

The fact is I could have taken any song from Highway 61 Revisited and put it approximately here, or spread them all up and down this list—it's my favorite album and has been for as long as I can remember and somehow it stays fresh and bracing every time I come back to it, even broken down to constituent parts. But this is the song that I recall amazing me first and most, doing things I didn't know could be done in a song or anything like it. It proceeds like a dream, a nightmare of powerlessness from the point of view of the tormentor, existing languidly within the smoky music of that remarkable session. It's at once funny and caustic. I laughed at parts of it like it was a stand-up routine: "And you say 'What does this mean?' and he screams back 'You're a cow / 'Give me some milk or else go home.'" And I gulped at others, recognizing myself in Mr. Jones nearly as much as I recognized myself (or the desire for it to be myself) in the ultra-cool uber-hip insider singing the song. One has only to see Dylan's treatment of Donovan in the D.A. Pennebaker documentary Don't Look Back to realize that a good deal of the time, at this point in his career, he was trading in the kind of alienating clique-mongering that's more appropriate to junior-high kids (and there are any number of reasonable explanations for that, given the totality of his experience at the time). Yet "Ballad of a Thin Man" is as seductive a portrait of the impulse as can be found anywhere, and a fine example of the pure blasts of dazzling language that populate that album too. It still amazes me—even knowing that I have become someone, like Mr. Jones, who has been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald's books.

The fact is I could have taken any song from Highway 61 Revisited and put it approximately here, or spread them all up and down this list—it's my favorite album and has been for as long as I can remember and somehow it stays fresh and bracing every time I come back to it, even broken down to constituent parts. But this is the song that I recall amazing me first and most, doing things I didn't know could be done in a song or anything like it. It proceeds like a dream, a nightmare of powerlessness from the point of view of the tormentor, existing languidly within the smoky music of that remarkable session. It's at once funny and caustic. I laughed at parts of it like it was a stand-up routine: "And you say 'What does this mean?' and he screams back 'You're a cow / 'Give me some milk or else go home.'" And I gulped at others, recognizing myself in Mr. Jones nearly as much as I recognized myself (or the desire for it to be myself) in the ultra-cool uber-hip insider singing the song. One has only to see Dylan's treatment of Donovan in the D.A. Pennebaker documentary Don't Look Back to realize that a good deal of the time, at this point in his career, he was trading in the kind of alienating clique-mongering that's more appropriate to junior-high kids (and there are any number of reasonable explanations for that, given the totality of his experience at the time). Yet "Ballad of a Thin Man" is as seductive a portrait of the impulse as can be found anywhere, and a fine example of the pure blasts of dazzling language that populate that album too. It still amazes me—even knowing that I have become someone, like Mr. Jones, who has been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald's books.

Sunday, November 27, 2011

Best American Crime Writing 2005

This edition of the redoubtable series credits James Ellroy with an "Introduction and an Original Essay," which I take to mean Ellroy didn't participate closely or at all in the actual selection of pieces here. I have enjoyed Ellroy's nonfiction work, particularly his memoir My Dark Places, but I'm not much of a fan of his fiction. But you can't blame series editors Otto Penzler and Thomas H. Cook for bringing in the marquee talent when possible, and certainly Ellroy qualifies as that much. His introduction is brief and by the numbers, and the original essay, which pays tribute to Joseph Wambaugh, is pro forma, Ellroy style. I hope the name helped it sell a lot of books and keep the series going. If it would help, I would be happy to see Ellroy do the same again for the 2011 edition, which appears more than ever to have gone MIA. This 2005 edition is in all ways a worthy entry; I haven't yet, I say again, seen the series dip even close to mediocre. This one includes a great long piece from "The New Yorker" by Lawrence Wright (author in 2006 of the exhaustive The Looming Tower as well as a much earlier favorite of mine, Remembering Satan) about the commuter-train bombings in Madrid that took place on March 11, 2004. The bombings killed some 191 and injured hundreds more and were eventually linked indirectly to (that is, inspired by) al-Qaeda. Wright's piece is a fascinating tick-tock that works to unravel the complexity of cultural connections and the very old and often bad blood between Christian and Islamic cultures, persisting more virulently than ever in the Internet age. And speaking of the Internet age, another piece, by Clive Thompson from "The New York Times Magazine," visits the shadowy, intriguing, and often infuriating world of the miscreants who create computer viruses, trojan horses, worms, and whatnot and spread them on the Internet. They're clever about it, often trading on our own worst impulses, and even when someone manages to track them down there is many times little legal recourse. Some seven or eight years old now, it's a bit dated but as interesting as ever. I think my favorite in this volume is another long piece from "The New Yorker" (I tell you, if this series is anything to go by that magazine remains our best source of true-crime literature), by David Grann, which details the mysterious death of Richard Lancelyn Green, "the world's foremost expert on Sherlock Holmes." At the time of his death, Green was embroiled in some kind of intrigue involving highly valuable papers of Arthur Conan Doyle that were to be donated to the British Library but instead somehow ended up going for sale via Christie's auction house. Green was investigating, believing the papers had been stolen, and he was subsequently found dead in his home, with a black shoelace around his neck and a wooden spoon in his hand. It's a mystery and a genuine whodunit, ruled a suicide but with more similarities to the Sherlock Holmes story "The Problem of Thor Bridge" (in which a suicide is deliberately contrived to look like a murder in order to implicate an enemy of the suicide) than to an actual suicide. Case still unsolved if a murder.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, November 26, 2011

It's a Wonderful Life (2001)

With a host of recognizable names on board making guest appearances, headed up by Tom Waits and PJ Harvey (and including John Parrish, Vic Chesnutt, Jane Scarpantoni, Nine Persson of the Cardigans, and others), this just might qualify as the highest-profile and maybe the single best album we ever got from Mark Linkous of Richmond, Virginia, aka Sparklehorse. It's my favorite, but it's also the one I know best, which might make it a kind of circular self-fulfilling prophecy. It's anyway usually my first impulse when inclined in the direction—warm and serious and plays like the night, starry and enveloping and good to return to every 24 hours or so. The songs are uniformly brave, lovely, allusive, often fragmentary, pointed toward single idealized moments of burnished beauty, and they are built out of strange materials that would occur to few others, strings and raw noise and lovely keyboards and acoustic guitar chords and random open spaces and Linkous's gentle wheedling vocal. After a career until then spent mostly working his songs out by himself alone in the studio the presence of a band and guests does provide a certain charge. "Dog Door," the relatively short song that Waits works on, certainly jumps out to the casual listener. Spend time with the album, however, and it becomes as much of a piece as all the rest here, and that's the real beauty. Harvey and the others are mostly integrated seamlessly, almost invisibly so. For a long time, before I got a look at the album credits, I thought the guitar and vocal harmonies on "Piano Fire," for example, sounded a lot like something I already knew. But I never guessed it was Harvey, provoking a kind of delicious forehead-smacking moment. I don't know why I'm going on about all this—I guess it's the easy thing to write about. The real thing is that this is some of Linkous's best songwriting, the kind of stuff that will stick with you a long time and come back in an instant every time you return, and if it sounds strange and even a little alienating the first time or two it only gets better. I know I keep a perhaps overly careful and tenuous distance from ongoing currencies in music, but his death last year reached even me, and I recognized it as the kind of loss that only grows in effect, a loss for all of us.

Friday, November 25, 2011

Apocalypse Now (1979)

USA, 202 minutes (Redux, 2001)

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Writers: Joseph Conrad, John Milius, Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Herr

Photography: Vittorio Storaro

Music: Carmine Coppola, Francis Ford Coppola

Editors: Lisa Fruchtman, Gerald B. Greenberg, Walter Murch

Cast: Martin Sheen, Robert Duvall, Frederic Forrest, Marlon Brando, Sam Bottoms, Dennis Hopper, Laurence Fishburne, Albert Hall, Harrison Ford, G.D. Spradlin, Francis Ford Coppola, Scott Glenn, Jack Thibeau, Herb Rice, Christian Marquand, Aurore Clement

Apocalypse Now has long been preceded by the legendary stories of its troubled production, one of those film enterprises that appears oddly cursed (The Exorcist is another), whose backstories may be nearly as entertaining as the final product itself: in this case, weathering a typhoon that wrecked the sets, condemnation from the Animal Humane Society for filming the ritual slaughter of a water buffalo, Marlon Brando at this stage in his career, and various haphazard budget overruns and casting adventures (e.g., Harvey Keitel dumped at the last minute for Martin Sheen, who subsequently suffered a heart attack during the shoot). All this and more is ably detailed in the documentary Hearts of Darkness, which makes a worthy companion piece for a night of Apocalypse Now.

The final result is hardly flawless. Attempting to transpose Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness on America's Vietnam adventure, it's very nearly torpedoed by Brando's performance in the final hour, and it's often marked by an impulse to amp up the drama beyond what its fundamentals can support. Yet for all that it contains unforgettable sequences and, in its totality, becomes unforgettable itself, using Heart of Darkness as its ticket into an even deeper American story, Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn, which is also set on a river (only going in the other direction), also episodic, also with an unsatisfactory ending—and also somehow vastly bigger than the sum of its parts.

Director: Francis Ford Coppola

Writers: Joseph Conrad, John Milius, Francis Ford Coppola, Michael Herr

Photography: Vittorio Storaro

Music: Carmine Coppola, Francis Ford Coppola

Editors: Lisa Fruchtman, Gerald B. Greenberg, Walter Murch

Cast: Martin Sheen, Robert Duvall, Frederic Forrest, Marlon Brando, Sam Bottoms, Dennis Hopper, Laurence Fishburne, Albert Hall, Harrison Ford, G.D. Spradlin, Francis Ford Coppola, Scott Glenn, Jack Thibeau, Herb Rice, Christian Marquand, Aurore Clement

Apocalypse Now has long been preceded by the legendary stories of its troubled production, one of those film enterprises that appears oddly cursed (The Exorcist is another), whose backstories may be nearly as entertaining as the final product itself: in this case, weathering a typhoon that wrecked the sets, condemnation from the Animal Humane Society for filming the ritual slaughter of a water buffalo, Marlon Brando at this stage in his career, and various haphazard budget overruns and casting adventures (e.g., Harvey Keitel dumped at the last minute for Martin Sheen, who subsequently suffered a heart attack during the shoot). All this and more is ably detailed in the documentary Hearts of Darkness, which makes a worthy companion piece for a night of Apocalypse Now.

The final result is hardly flawless. Attempting to transpose Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness on America's Vietnam adventure, it's very nearly torpedoed by Brando's performance in the final hour, and it's often marked by an impulse to amp up the drama beyond what its fundamentals can support. Yet for all that it contains unforgettable sequences and, in its totality, becomes unforgettable itself, using Heart of Darkness as its ticket into an even deeper American story, Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn, which is also set on a river (only going in the other direction), also episodic, also with an unsatisfactory ending—and also somehow vastly bigger than the sum of its parts.

Thursday, November 24, 2011

20. Leon Russell, "Me and Baby Jane" (1972)

(listen)

Sometimes it feels like Leon Russell has been lost to history since even before the '70s ended, dwelling forever there with his makeup and top hat and hair as one of the clownish features of the times, with maybe Leo Sayer, Minnie Riperton, and Carl Douglas. But I have never been able to get a handful of his songs out of my head, most of them circa 1972 and the album Carney—"Magic Mirror," "Tight Rope," a few others, but more than any this woeful hymn to a love affair ruined forever by heroin and death. At the time I was hearing it on the radio (how it got there I don't know) it never failed to leap out and get me by the throat, though I had no concrete connection with any of its themes or scenarios. I just had some idea how it felt, and the feelings were overwhelming, love arrived and gone forever. The croak of Russell's voice, now and then missing its intended notes, the softly marching tempo at the chorus, and the signature rich tones of his piano playing throughout serve him well. It uses the drug lifestyle just right—though no doubt the reason it never made the hit parade—never glorifying but never judging or condemning or blaming either, and hardly shrinking from it. Just a brief memory of "the needle in her vein" to etch the image in. I'm not sure exactly how Leon Russell does what he does—sometimes I'm not even sure what it is he's doing exactly—but "Me and Baby Jane" may be the best single example of him doing it: swooningly sad, ripe to the point of bursting, dramatized within an inch of its life, yet somehow softly understated, always tender, and above all completely beautiful.

Sometimes it feels like Leon Russell has been lost to history since even before the '70s ended, dwelling forever there with his makeup and top hat and hair as one of the clownish features of the times, with maybe Leo Sayer, Minnie Riperton, and Carl Douglas. But I have never been able to get a handful of his songs out of my head, most of them circa 1972 and the album Carney—"Magic Mirror," "Tight Rope," a few others, but more than any this woeful hymn to a love affair ruined forever by heroin and death. At the time I was hearing it on the radio (how it got there I don't know) it never failed to leap out and get me by the throat, though I had no concrete connection with any of its themes or scenarios. I just had some idea how it felt, and the feelings were overwhelming, love arrived and gone forever. The croak of Russell's voice, now and then missing its intended notes, the softly marching tempo at the chorus, and the signature rich tones of his piano playing throughout serve him well. It uses the drug lifestyle just right—though no doubt the reason it never made the hit parade—never glorifying but never judging or condemning or blaming either, and hardly shrinking from it. Just a brief memory of "the needle in her vein" to etch the image in. I'm not sure exactly how Leon Russell does what he does—sometimes I'm not even sure what it is he's doing exactly—but "Me and Baby Jane" may be the best single example of him doing it: swooningly sad, ripe to the point of bursting, dramatized within an inch of its life, yet somehow softly understated, always tender, and above all completely beautiful.

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

21. Eminem, "Kim" (2000)

(listen/NSFW)

A strange and remarkable hybrid of pop song (you can sing with the chorus!) and relentless radio-theater horror movie, this is the best example I know of Eminem's ability to make his own interior life vivid and disturbingly recognizable enough that it literally sends people shrieking from the room when it plays—well, maybe figuratively. "Kim" is so stunning in its details that, simply hearing it, one feels one has actually witnessed or even been party to a crime. It's what makes it challenging to enter into and engage with and judge—it took me weeks just to get all the way through it. Now I find it riveting, powerful, and quite moving, horrific in its details but a picture of a person so real, in so much pain, that it's impossible to deny. Things like this, let's call them "transgressive," have all kinds of ways to go wrong. Too often they feel merely like someone stretching limits for the sake of stretching limits, pushing beyond believability into easy outrage or, worse, jokey mocking excess, and ultimately they come off like a cheat. "Kim," by contrast, pulls in the other direction, as if Eminem knew well how far out he was going to have to go with this, took a deep breath, and, for the six minutes it lasts, threw himself into the project of blasting it out of himself once and for all with everything he had. It's poised, sharp, wicked, funny, thrilling, mortifying, and terribly sad all at once. It's just remarkable. Sheila O'Malley did way more justice to it at her blog earlier this year than I am even coming close to, so I will take the easy way out and quit trying now and just point to her piece.

A strange and remarkable hybrid of pop song (you can sing with the chorus!) and relentless radio-theater horror movie, this is the best example I know of Eminem's ability to make his own interior life vivid and disturbingly recognizable enough that it literally sends people shrieking from the room when it plays—well, maybe figuratively. "Kim" is so stunning in its details that, simply hearing it, one feels one has actually witnessed or even been party to a crime. It's what makes it challenging to enter into and engage with and judge—it took me weeks just to get all the way through it. Now I find it riveting, powerful, and quite moving, horrific in its details but a picture of a person so real, in so much pain, that it's impossible to deny. Things like this, let's call them "transgressive," have all kinds of ways to go wrong. Too often they feel merely like someone stretching limits for the sake of stretching limits, pushing beyond believability into easy outrage or, worse, jokey mocking excess, and ultimately they come off like a cheat. "Kim," by contrast, pulls in the other direction, as if Eminem knew well how far out he was going to have to go with this, took a deep breath, and, for the six minutes it lasts, threw himself into the project of blasting it out of himself once and for all with everything he had. It's poised, sharp, wicked, funny, thrilling, mortifying, and terribly sad all at once. It's just remarkable. Sheila O'Malley did way more justice to it at her blog earlier this year than I am even coming close to, so I will take the easy way out and quit trying now and just point to her piece.

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

22. Lou Reed, "Perfect Day" (1972)

(listen)

Here's one truly that moves in mysterious ways—I've been aware of it ever since I was aware of Transformer, my first real introduction to Lou Reed, but it wasn't until I saw the way it was used in the movie Trainspotting that I came to embrace it (it later became a memorably star-studded BBC promo, and frequently covered elsewhere as well, but I think the original is still the best). On its face it is hilarious, a croaking monotone Lou Reed barely getting over the swooning orchestra he reclines on so luxuriously, with a swelling Liberace by way of Ferrante & Teicher hammering on a grand piano at the bridge that sends it swirling to the heavens. The theme? Remembering the good times through a haze of bitterness. "I thought I was / Someone else, someone good." The good times may be saccharine, the bitterness arch, but it remains a place we likely all know. Reed plays it straight on every measure and that's the key to the irony—if, indeed, there is a shred of irony in this at all. As likely as not the irony is imposed by the listener, by you and me, made rattling uncomfortable and awkward by the straightforward plainspokenness and a concomitant unwillingness to, er, feel the feelings. The things that constitute this perfect day—drinking Sangria in the park, feeding animals in the zoo, then later a movie too—are so unexpected, so homely, so pretty, and so right, that you just have to laugh in recognition. Or bawl your eyes out, depending on the mood. And then listen again to make sure you got it all right. I can't blame anyone for trying to figure out how this even works at all, let alone works so well.

Here's one truly that moves in mysterious ways—I've been aware of it ever since I was aware of Transformer, my first real introduction to Lou Reed, but it wasn't until I saw the way it was used in the movie Trainspotting that I came to embrace it (it later became a memorably star-studded BBC promo, and frequently covered elsewhere as well, but I think the original is still the best). On its face it is hilarious, a croaking monotone Lou Reed barely getting over the swooning orchestra he reclines on so luxuriously, with a swelling Liberace by way of Ferrante & Teicher hammering on a grand piano at the bridge that sends it swirling to the heavens. The theme? Remembering the good times through a haze of bitterness. "I thought I was / Someone else, someone good." The good times may be saccharine, the bitterness arch, but it remains a place we likely all know. Reed plays it straight on every measure and that's the key to the irony—if, indeed, there is a shred of irony in this at all. As likely as not the irony is imposed by the listener, by you and me, made rattling uncomfortable and awkward by the straightforward plainspokenness and a concomitant unwillingness to, er, feel the feelings. The things that constitute this perfect day—drinking Sangria in the park, feeding animals in the zoo, then later a movie too—are so unexpected, so homely, so pretty, and so right, that you just have to laugh in recognition. Or bawl your eyes out, depending on the mood. And then listen again to make sure you got it all right. I can't blame anyone for trying to figure out how this even works at all, let alone works so well.

Monday, November 21, 2011

23. Rolling Stones, "Street Fighting Man" (1968)

(listen)

A friend and I were agreeing the other day that over the long haul of the decades it seems more and more that the best Stones albums, the ones we most tend to return to again and live with, are the early half dozen or so—Now! and 12 X 5 and Out of Our Heads—and less so that more typically lionized run of the late '60s and early '70s that started with Beggars Banquet and finished with Exile on Main St. They really were a remarkable rock 'n' roll blues band before they were signifiers for a generation or anything else, and track by track those early albums still sound almost impossibly fresh. Yet, even so, one way or another, I never find myself drifting too far from Beggars Banquet, which is somehow deceptively less than the sum of its parts. But taken one item at a time it houses what seems to me to be their enduringly best, not the least of which, indeed the greatest of which, is this ratatat, irony-inflected paean to political street demonstrations of the times generally, and more specifically to Tariq Ali, a radicalized British Pakistani who has remained relevant long beyond the immediate life of this great, great song. Everything about it is rock hard, and rocks hard: Charlie Watts hits the drums impossibly hard, even for him, and the strange off-rhythms of Keith Richards's opening acoustic guitar are nothing less than electrifying. So that accounts for the first 10 seconds, and it only gets better from there. Jagger's melody lines crease with ferocity, keyboards and whining electric guitar and strings and other things steal in. It's potent with visceral energy, climaxing lyrically with the question, "What can a poor boy do but sing in a rock and roll band?" It's the one thing by them I would save if ever forced to such an extremity.

A friend and I were agreeing the other day that over the long haul of the decades it seems more and more that the best Stones albums, the ones we most tend to return to again and live with, are the early half dozen or so—Now! and 12 X 5 and Out of Our Heads—and less so that more typically lionized run of the late '60s and early '70s that started with Beggars Banquet and finished with Exile on Main St. They really were a remarkable rock 'n' roll blues band before they were signifiers for a generation or anything else, and track by track those early albums still sound almost impossibly fresh. Yet, even so, one way or another, I never find myself drifting too far from Beggars Banquet, which is somehow deceptively less than the sum of its parts. But taken one item at a time it houses what seems to me to be their enduringly best, not the least of which, indeed the greatest of which, is this ratatat, irony-inflected paean to political street demonstrations of the times generally, and more specifically to Tariq Ali, a radicalized British Pakistani who has remained relevant long beyond the immediate life of this great, great song. Everything about it is rock hard, and rocks hard: Charlie Watts hits the drums impossibly hard, even for him, and the strange off-rhythms of Keith Richards's opening acoustic guitar are nothing less than electrifying. So that accounts for the first 10 seconds, and it only gets better from there. Jagger's melody lines crease with ferocity, keyboards and whining electric guitar and strings and other things steal in. It's potent with visceral energy, climaxing lyrically with the question, "What can a poor boy do but sing in a rock and roll band?" It's the one thing by them I would save if ever forced to such an extremity.

Sunday, November 20, 2011

The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath & Ted Hughes (1994)

I read this not so much because I was interested in Sylvia Plath, though I've come to have a good deal of respect and admiration for her work, but more because I was interested in the work of Janet Malcolm generally and specifically for her take on "the biographical enterprise," which is the theme of this book at least as much as it is Plath. And incidentally because at the time this was published I had some ideas of my own about taking on a biography, of a figure who seemed to me to occupy a point equidistant between Plath and Hank Williams—Williams, who may (or may not) have committed suicide proper, but at the very least drank himself purposefully to death, with a harpy at his side shrieking away. Thus many of Malcolm's most trenchant points about suicide and/or the various impossibilities of biography I now find underscored in my copy of the book rather forcefully ("As sleep is necessary to our physiology, so depression seems necessary to our psychic economy," "In a work of nonfiction we almost never know the truth of what happened," etc.). Going through it again recently, I enjoyed Malcolm's wry pleasure at inserting herself into the fraught perils of Sylvia Plath's and Ted Hughes's lives. Hughes died in 1998, nearly five years after the publication of this book. I never followed up enough to know Malcolm's thoughts or actions after such a momentous occasion, or indeed anyone else's involved in the Plath biography industry, with the removal of such a monumental obstacle to the project. For the most part here Malcolm trudges down all the previously trod pathways, not unearthing much new as far as I can tell, but bringing her razor-sharp sensibility to bear, one that is particularly well-suited, I think, to Plath's own at the height of her powers in the last year of her life. Lots of unpleasant people populate this narrative, many of whom clash unpleasantly with one another. I do know the Ann Stevenson biography that animates so much here, Bitter Fame—animates Malcolm herself, who evidently knew of Stevenson when they were both going to college in Michigan. When Malcolm says Stevenson's book is the best biography of the bunch then existing I'm perfectly willing to take her at her word. I remember thinking pretty well of it myself, though I could have had no idea of all the stresses and tensions Stevenson endured to get it done. Malcolm at least seems to have had a milder time of putting hers together, the chief strength of which is in her ability to deal on particularly conscious levels with the sideline "meta" issues that shape and distort the narratives of biographies.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, November 19, 2011

The Temptations Sing Smokey (1965)

Probably few would argue with the idea that Motown, as a label, was best at chucking out nonstop streams of hit singles. But now and then, across the colossal breadth of the catalog, whole albums will turn up that are worth tracking down and snapping up—and not just those sponsored by Marvin Gaye or Stevie Wonder. This is a prime example right here. It's practically a concept album in its way, combining the marquee act Temptations on the one hand with one of the label's best songwriters (with and without assorted other Miracles), Smokey Robinson. What's particularly appealing here is how nicely it cuts across the various looks of the act, with David Ruffin, Eddie Kendricks, and Paul Williams each getting their individual shots to shine as lead singers, as well as various combinations of them and others (such as Melvin Franklin and Otis Williams) and the group in ensemble. I guess Ruffin tends to be my favorite Temptation, but there are cases to be made for them all, and perhaps most of all for the versatility of the act itself. There are big hits here—"My Girl," "The Way You Do the Things You Do," and "It's Growing"—along with straight-up covers that other artists got the hits with, including the Miracles themselves: "You Beat Me to the Punch," "You've Really Got a Hold on Me," "What's So Good About Good Bye." But the central concept holds for every one of the dozen songs here: Smokey Robinson had a hand in writing them, the Temptations performed them. And that's it. The result does not go on any longer than 35 minutes, except it's easy enough to lengthen out by playing over and over and over, back to back to back. It does no harm to this set—in fact, the music just gets better with such familiarity, as any number of fine points continue to disclose themselves: the always clever word play of Smokey's lyrics, a handful of particularly nice arrangements from the Funk Brothers (the guitar support on "You'll Lose a Precious Love" just jumped out at me a minute ago), and/or simply the knack the Temptations so often demonstrated for any of a number of different ways to stand a song up and get it to hold its position forever in one's memory. This is some highly durable product.

Friday, November 18, 2011

Breathless (1960)

À bout de soufflé, France, 90 minutes

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Writers: Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard

Photography: Raoul Coutard

Music: Martial Solal

Editors: Cecile Decugis, Lila Herman

Cast: Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jean Seberg, Daniel Boulanger, Jean-Pierre Melville

I better cop to a problem with Jean-Luc Godard right up front, if only as a matter of fair warning: hidebound conventions (and spoilers) directly ahead. Godard is and remains, for me, an acknowledged blind spot, likely weighed down as much as anything by the imposing reputation that has preceded him practically since the day I first heard of him. His most widely hailed pictures—and Breathless, his feature debut, is the first among them in many ways, along with Pierrot le fou, which affects me similarly, and Contempt, which seems slightly a bit of a different animal, but all that in due time—tend to strike me as monumentally silly or academically pretentious or both, the result of children playacting with motion picture technology.

I will grant these are no ordinary children—they have levels of aesthetic sophistication, and no small degree of high critical argle-bargle, to back themselves up. Godard seems to me to be continually about finding ways to demonstrate he is a million times smarter than anyone else in the (darkened) room, which his followers are as much at pains to defend seemingly on any terms within reach, on grounds of avant-garde experimentalism, defiant anti-convention, unique vision, I-know-you-are-but-what-is-he, the continuing perception of a widespread and penetrating influence, and as many others as can be and are adduced in seminar environments. And all that may be true enough. But they do tend to derive almost purely from the cerebrum. My problem is more acutely with the overall experience his pictures tend to deliver for me, which is narrow and small.

Director: Jean-Luc Godard

Writers: Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard

Photography: Raoul Coutard

Music: Martial Solal

Editors: Cecile Decugis, Lila Herman

Cast: Jean-Paul Belmondo, Jean Seberg, Daniel Boulanger, Jean-Pierre Melville

I better cop to a problem with Jean-Luc Godard right up front, if only as a matter of fair warning: hidebound conventions (and spoilers) directly ahead. Godard is and remains, for me, an acknowledged blind spot, likely weighed down as much as anything by the imposing reputation that has preceded him practically since the day I first heard of him. His most widely hailed pictures—and Breathless, his feature debut, is the first among them in many ways, along with Pierrot le fou, which affects me similarly, and Contempt, which seems slightly a bit of a different animal, but all that in due time—tend to strike me as monumentally silly or academically pretentious or both, the result of children playacting with motion picture technology.

I will grant these are no ordinary children—they have levels of aesthetic sophistication, and no small degree of high critical argle-bargle, to back themselves up. Godard seems to me to be continually about finding ways to demonstrate he is a million times smarter than anyone else in the (darkened) room, which his followers are as much at pains to defend seemingly on any terms within reach, on grounds of avant-garde experimentalism, defiant anti-convention, unique vision, I-know-you-are-but-what-is-he, the continuing perception of a widespread and penetrating influence, and as many others as can be and are adduced in seminar environments. And all that may be true enough. But they do tend to derive almost purely from the cerebrum. My problem is more acutely with the overall experience his pictures tend to deliver for me, which is narrow and small.

Thursday, November 17, 2011

24. Johnny Cash, "Folsom Prison Blues" (1955)

(listen)

This is a country standard now, covered far and wide by artists including Charley Pride, Slim Harpo, and the Reverend Horton Heat, which is some indication right there of the range of its appeal. It's also become one of a handful of Johnny Cash's signature songs, easily my favorite among them, but gosh, he made a whole lot of really great songs. It's closer to American folk idioms, self-consciously drawing on familiar and well-worked traditions of both train and prison songs. But it's so dark, largely the work of the one famously memorable line—"I shot a man in Reno / Just to watch him die"—that it remains as fresh as ever, decades on. The Sun version is the one I like best, though Cash is one of those artists whose work is worth chasing down in all its forms, live performances, outtakes, alternate versions, even covers and tributes by others, the whole shebang. There's a popular version from the late '60s, recorded live at Folsom Prison itself (and sweetened some in the mix to make it sound more raw and desperate), that's nearly as popular as his first run at it in the mid-'50s. But the original Sun version is such a model of the form, stripped down to essentials, occupying a kind of eerie hush that entirely gets out of the way of the song proper, just Marshall Grant playing bass, Luther Perkins playing a spidery, barbed-wire electric guitar, and Johnny Cash sounding as lonesome and lost as he ever did, which is saying something. The melody is plain and lovely and sticks—if anything, Cash may have been underrated as a songwriter. If the whole thing doesn't last even three minutes, it always sounds good, and the more closely you listen the more it gets under your skin.

This is a country standard now, covered far and wide by artists including Charley Pride, Slim Harpo, and the Reverend Horton Heat, which is some indication right there of the range of its appeal. It's also become one of a handful of Johnny Cash's signature songs, easily my favorite among them, but gosh, he made a whole lot of really great songs. It's closer to American folk idioms, self-consciously drawing on familiar and well-worked traditions of both train and prison songs. But it's so dark, largely the work of the one famously memorable line—"I shot a man in Reno / Just to watch him die"—that it remains as fresh as ever, decades on. The Sun version is the one I like best, though Cash is one of those artists whose work is worth chasing down in all its forms, live performances, outtakes, alternate versions, even covers and tributes by others, the whole shebang. There's a popular version from the late '60s, recorded live at Folsom Prison itself (and sweetened some in the mix to make it sound more raw and desperate), that's nearly as popular as his first run at it in the mid-'50s. But the original Sun version is such a model of the form, stripped down to essentials, occupying a kind of eerie hush that entirely gets out of the way of the song proper, just Marshall Grant playing bass, Luther Perkins playing a spidery, barbed-wire electric guitar, and Johnny Cash sounding as lonesome and lost as he ever did, which is saying something. The melody is plain and lovely and sticks—if anything, Cash may have been underrated as a songwriter. If the whole thing doesn't last even three minutes, it always sounds good, and the more closely you listen the more it gets under your skin.

Wednesday, November 16, 2011

25. Prince, "Sexuality" (1981)

(listen)

Yet another living room classic for me—I knew of Dirty Mind, but the album that hosts this scorching hot romp, Controversy, happened to be my first real introduction to the many pleasures of Prince, a good deal of them present here. It's fast and nimble as can be, launched on a scream and never stopping or slowing once until the end. And couldn't be more plain about where it's coming from, what drove him, his message boiled down to essentials: "Sexuality is all I'll ever need / Sexuality, I'm gonna let my body be free." I put this on, volume up, and danced, by myself or with whoever was handy. It's plain irresistible. And that was my life at least once a day, day or night, for several weeks. It has remained one I can return to virtually any time. I've talked before about the spoken/chanted interlude that emerges out of nowhere in the middle of it; it's precious, crazy, wacked, insane, very funny, and bears a kind of grace achieved by few: "We live in a world overrun by tourists. Tourists—89 flowers on their back. Inventors of the Accu-jack. They look at life through a pocket camera. What? No flash again? They're all a bunch of double drags who teach their kids that love is bad. Half of the staff of their brain is on vacation." And so forth. The pleasure of it is how neatly it's integrated, how he uncorks it and lets it unreel, even as he stops, pops, and shoots within the complexity of the rhythms of it. It's amazing and you have to hear it. And, while you're doing so, please, my advice: Let your body be free.

Yet another living room classic for me—I knew of Dirty Mind, but the album that hosts this scorching hot romp, Controversy, happened to be my first real introduction to the many pleasures of Prince, a good deal of them present here. It's fast and nimble as can be, launched on a scream and never stopping or slowing once until the end. And couldn't be more plain about where it's coming from, what drove him, his message boiled down to essentials: "Sexuality is all I'll ever need / Sexuality, I'm gonna let my body be free." I put this on, volume up, and danced, by myself or with whoever was handy. It's plain irresistible. And that was my life at least once a day, day or night, for several weeks. It has remained one I can return to virtually any time. I've talked before about the spoken/chanted interlude that emerges out of nowhere in the middle of it; it's precious, crazy, wacked, insane, very funny, and bears a kind of grace achieved by few: "We live in a world overrun by tourists. Tourists—89 flowers on their back. Inventors of the Accu-jack. They look at life through a pocket camera. What? No flash again? They're all a bunch of double drags who teach their kids that love is bad. Half of the staff of their brain is on vacation." And so forth. The pleasure of it is how neatly it's integrated, how he uncorks it and lets it unreel, even as he stops, pops, and shoots within the complexity of the rhythms of it. It's amazing and you have to hear it. And, while you're doing so, please, my advice: Let your body be free.

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

26. Velvet Underground, "I'm Waiting for the Man" (1967)

(listen)

The banana album (formally, The Velvet Underground & Nico) was my first real exposure to the band, as before that I hadn't taken the opportunity to examine them closely and by then, honestly, it was already the early '80s, when I finally brought home a copy from the record store. One of those necessity purchases procrastinated, I guess—and I wish I had all those years back now so I could hear it that much more often. After the low-key and utterly pleasant overture of "Sunday Morning" this comes along to set the basic terms: a monotony of driving rhythm with pounding instruments stacked on top, packaged with a patented Story of Gritty Urban Reality™ (in this case scoring heroin out of Harlem). It's full of small wisdoms ("First thing you learn is that you always gotta wait") and sly humor ("Oh pardon me sir, it's furthest from my mind"), and it affords itself a good deal of untoward glee as it wallows in the various indignities and ultimate pleasures of the adventure it describes. But mostly it's fast and rocks righteous hard, functioning like a rave-up with a sour aftertaste, a gathering storm that can blow down houses, a pummeling beatdown you don't soon forget. For me, it always, always rewards turning up the volume, and for the first six months or so that I owned the album I rarely finished listening to this song not standing on my feet. It's one for waving your hands in the air like you just don't care and carrying on like a regular fool, and damn the neighbors pounding on the walls and ceiling.

The banana album (formally, The Velvet Underground & Nico) was my first real exposure to the band, as before that I hadn't taken the opportunity to examine them closely and by then, honestly, it was already the early '80s, when I finally brought home a copy from the record store. One of those necessity purchases procrastinated, I guess—and I wish I had all those years back now so I could hear it that much more often. After the low-key and utterly pleasant overture of "Sunday Morning" this comes along to set the basic terms: a monotony of driving rhythm with pounding instruments stacked on top, packaged with a patented Story of Gritty Urban Reality™ (in this case scoring heroin out of Harlem). It's full of small wisdoms ("First thing you learn is that you always gotta wait") and sly humor ("Oh pardon me sir, it's furthest from my mind"), and it affords itself a good deal of untoward glee as it wallows in the various indignities and ultimate pleasures of the adventure it describes. But mostly it's fast and rocks righteous hard, functioning like a rave-up with a sour aftertaste, a gathering storm that can blow down houses, a pummeling beatdown you don't soon forget. For me, it always, always rewards turning up the volume, and for the first six months or so that I owned the album I rarely finished listening to this song not standing on my feet. It's one for waving your hands in the air like you just don't care and carrying on like a regular fool, and damn the neighbors pounding on the walls and ceiling.

Monday, November 14, 2011

27. Who, "My Generation" (1965)

(listen)

This one surprises me still every time I encounter it again. It never made the radio where I was, though I recall hearing it show up on oldies stations now and again, always fresh and exciting and sudden. I'd known about it from reading Nik Cohn's Rock From the Beginning when I was 15, which made it absolutely one thing I was intent on tracking down immediately. Cohn wrote: " ... the Mod was trying to justify himself, wanted to lash back at everyone who'd ever put him down, but he'd taken too many pills and couldn't concentrate right. He only stammered. He was mad, frustrated, but he wasn't articulate; he couldn't say why. The harder he tried, the worse he stammered, the more he got confused. In the end, he got nowhere: 'People try to put us down / Just because we get around, / Things they do look awful cold, / Hope I die before I get old.'" Cohn got that all about right, and certainly it did the job of setting me into action, which is the effect that the best rock criticism should have. Even in 1969 it wasn't easy to recognize the staying power of one of the great lines of rock 'n' roll, "Hope I die before I get old," which we can see now will likely survive all of us (even as we think we are clever by turning it around and hoping now that we get old first, as many of us have). Cohn also neglected to talk about how brash and galvanizing it sounds. It's not exactly noisy, there's plenty of open spaces in and around the racket, and the guitar even sounds acoustic, at least in the early going. But the way they're playing, as if abusing and beating up their instruments, hitting everything so hard—it really gets your attention.

This one surprises me still every time I encounter it again. It never made the radio where I was, though I recall hearing it show up on oldies stations now and again, always fresh and exciting and sudden. I'd known about it from reading Nik Cohn's Rock From the Beginning when I was 15, which made it absolutely one thing I was intent on tracking down immediately. Cohn wrote: " ... the Mod was trying to justify himself, wanted to lash back at everyone who'd ever put him down, but he'd taken too many pills and couldn't concentrate right. He only stammered. He was mad, frustrated, but he wasn't articulate; he couldn't say why. The harder he tried, the worse he stammered, the more he got confused. In the end, he got nowhere: 'People try to put us down / Just because we get around, / Things they do look awful cold, / Hope I die before I get old.'" Cohn got that all about right, and certainly it did the job of setting me into action, which is the effect that the best rock criticism should have. Even in 1969 it wasn't easy to recognize the staying power of one of the great lines of rock 'n' roll, "Hope I die before I get old," which we can see now will likely survive all of us (even as we think we are clever by turning it around and hoping now that we get old first, as many of us have). Cohn also neglected to talk about how brash and galvanizing it sounds. It's not exactly noisy, there's plenty of open spaces in and around the racket, and the guitar even sounds acoustic, at least in the early going. But the way they're playing, as if abusing and beating up their instruments, hitting everything so hard—it really gets your attention.

Sunday, November 13, 2011

The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones (1984)

Stanley Booth is an American music journalist from the South. He happened to fall into the orbit of the Rolling Stones shortly after the death of Brian Jones, and was on hand for a good deal of the band's first extensive tour in several years in 1969, including the ill-starred show at Altamont in December that year. Even the Stones formally recognize and acknowledge the legitimacy of Booth's reporting in a brief, vaguely mocking letter to him, dated October 21, 1969, which is reproduced in my 1985 paperback edition (I'm not familiar with the 2000 edition, which reportedly contains minor revisions and an afterword that discusses the writing of the first edition): "This letter assures you of the Rolling Stones' full and exclusive cooperation in putting together a book about the Stones for publication," and it's signed by Mick Jagger, Keith Richard, Charlie Watts, Bill Wyman, and Mick Taylor. It's fair enough to call this book a labor of love, but the emphasis there must fall on the "labor," as it took Booth some 15 years to complete and the language feels well worked over, honed and buffed to a point where it's occasionally a labor to read as well. But I don't know of anything better anywhere on the Stones, or particularly on Altamont, and it makes an excellent companion piece and counterpoint to the Maysles brothers well-known documentary Gimme Shelter; each is a nice tonic to the excesses and deficiencies of the other, and both offer converging yet significantly differing points of view that harmonize well. Both have also earned colossal burdens of reputation, hailed as landmark works about the times—figures of no less stature than Harold Brodkey and Robert Stone, for example, call Booth's book the best single volume on the '60s. OK, fair enough. I'm inclined myself to put that on a few other volumes first (Dispatches, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, Manchild in the Promised Land, or Catch-22 come to mind immediately). But I see how it works. And if I'm going to indulge hyperbole of my own here, it's for the 50-some pages that Booth devotes to the Altamont show proper, which open with a section of transcript from the discussion between Jerry Lee Lewis and Sam Phillips on the epistemology and ontology of evil, and hell, in the context of the song they are attempting to record, "Great Balls of Fire." It's an earnest and serious discussion, at least on the part of Lewis, steeped in old-time Christianity. Just so, I have never encountered anything anywhere that penetrates so deeply into the simple facts of what was happening that day at Altamont as Booth's book (and that includes Gimme Shelter, which I have always counted as impressive and important)—nor, more importantly, any more powerful, simple, and nuanced suggestions of "what it all meant." There are no easy answers here, and not much comfort. I should get that 2000 edition, if only to find out for sure what held up the writing of this for 15 years. But I have a feeling I might already know.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, November 12, 2011

Wind & Wuthering (1976)

This is approximately exactly what you might expect from mid-'70s post-Gabriel Genesis—long, densely structured, rarely inspired, occasionally pretty. I took home a copy of it from the used record store when it was still a fairly recent release, and found that, in patches, it sometimes fit a few moods quite nicely, something about late at night in Minnesota winters, locked in by snow but warm at whatever I was calling home at the moment. The "Wuthering" of the title, in case you were wondering, is indeed a reference to the Emily Bronte novel, with two tracks near the end of the second side evidently built around (or anyway directly named after) the novel's last sentence: "I lingered round them, under that benign sky: watched the moths fluttering among the heath and harebells, listened to the soft wind breathing through the grass, and wondered how any one could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth." In fact, "Unquiet Slumbers for the Sleepers..." (at 2:23 far and away the shortest track) and "...in That Quiet Earth" contain some of my favorite passages here. There are also some nice moments in "Blood on the Rooftops." But with the typically ornate way in which these often rather long tracks are put together—four of the nine coming in over six minutes, one of them practically 10 minutes, and all but two of the rest four minutes or more—there's a lack of focus and general aimlessness to them; only too infrequently do they become interesting. I know lack of focus and general aimlessness is more or less what they did, leavened with smatterings of British literary lore—I understand that, even understood it then. I recall enjoying a handful of their albums, sometimes even intensely (and not just The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, which I still like a fair bit). But it rarely comes back to me now, seemingly lost for good, and alas, much of this album was no exception recently. Mostly it sounds silly and self-indulgent and empty, which, OK, may have been suitable for me to some degree at one time. I find myself impatient with it now, even embarrassed for what they seem to think they are doing. It's nice and goes down smooth and everything, and bully for them that they know the Bronte novel. But nothing here is even within hailing distance of it.

Friday, November 11, 2011

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

UK, 95 minutes

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Writers: Stanley Kubrick, Terry Southern, Peter George

Photography: Gilbert Taylor

Music: Laurie Johnson

Editor: Anthony Harvey

Cast: Peter Sellers, George C. Scott, Peter Bull, Sterling Hayden, Keenan Wynn, Slim Pickens, James Earl Jones, Tracy Reed

There are a number of facts about the historical context of Dr. Strangelove I hadn't understood well before looking into the picture a bit more deeply. The original premiere, for example, was scheduled for November 22, 1963, which obviously meant it had to be postponed for several weeks. On that same tip there was even a scene that contained the line, "Gentlemen! Our gallant young president has just been struck down in his prime!"—part of a pie-throwing scene that sounds altogether too silly and was cut for that reason. It was cut before the assassination of John Kennedy happened, but you see what I'm getting at here.

In many ways, Dr. Strangelove stepped in as an augur of public moods to come and it exists there still, a model to be aspired to. As black comedies go, it's fairly obvious: inept bureaucracies unable to identify and ward off their threats from within find themselves on the brink of planetary annihilation. In response, those who ostensibly have the power to take action act like schoolchildren. Sounds familiar, doesn't it? If Stanley Kubrick hadn't been the one to get to it first, someone else would have, and not long after. It's been a theme returned to again and again since. So it's good, I think, that it was Kubrick who got there first.

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Writers: Stanley Kubrick, Terry Southern, Peter George

Photography: Gilbert Taylor

Music: Laurie Johnson

Editor: Anthony Harvey

Cast: Peter Sellers, George C. Scott, Peter Bull, Sterling Hayden, Keenan Wynn, Slim Pickens, James Earl Jones, Tracy Reed

There are a number of facts about the historical context of Dr. Strangelove I hadn't understood well before looking into the picture a bit more deeply. The original premiere, for example, was scheduled for November 22, 1963, which obviously meant it had to be postponed for several weeks. On that same tip there was even a scene that contained the line, "Gentlemen! Our gallant young president has just been struck down in his prime!"—part of a pie-throwing scene that sounds altogether too silly and was cut for that reason. It was cut before the assassination of John Kennedy happened, but you see what I'm getting at here.

In many ways, Dr. Strangelove stepped in as an augur of public moods to come and it exists there still, a model to be aspired to. As black comedies go, it's fairly obvious: inept bureaucracies unable to identify and ward off their threats from within find themselves on the brink of planetary annihilation. In response, those who ostensibly have the power to take action act like schoolchildren. Sounds familiar, doesn't it? If Stanley Kubrick hadn't been the one to get to it first, someone else would have, and not long after. It's been a theme returned to again and again since. So it's good, I think, that it was Kubrick who got there first.

Thursday, November 10, 2011

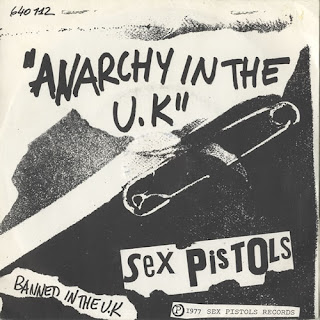

28. Sex Pistols, "Anarchy in the U.K." (1977)

(listen)

This is so obvious and, in a way, self-serving that I'm almost embarrassed to put it here. But long before it was the hallmark of a cultural earthquake/tidal wave that changed everything, etc., blahhh, it was this funny-weird song that a friend turned up on a 45 single. A 45 single! That by itself seemed strange enough at the time. Then it was this. Sure, there's a lot of scary sensation to it, big swaggering words like "anarchy" and "Antichrist" and all that unholy cackling from Johnny Rotten (later John Lydon), and plus he's not such a great singer you know, or anyway misses a lot of notes. But it's as much a pure pop song for now people as anything concocted by Nick Lowe and his Stiff brethren and that's exactly how I took it. I just loved it. Somebody put it on a tape for me, and I dubbed it from there onto all kinds of tapes for other people. I still think it's a pretty swell song, with a big raw wailing guitar sound and martial marching tempos, and all the howling and caterwauling from Lydon. There's something just thrilling about it. "There's so many ways to get what you want!" "It's the only way to be!" And, of course, the one that resonates across the ages, "I wanna destroy!" Each and every with an exclamation point embedded in the grain of the vocals and the emphatic kick of the band. I was perfectly prepared to accept this as the future of rock 'n' roll. I'm still not sure it wasn't, although by the time I was reading about them regularly in fan magazines they were pretty much over. They weren't exactly dead, they still aren't (and that includes poor old Sid). But they were over—an interesting state of affairs that this song utterly embodies, tensions and all.

This is so obvious and, in a way, self-serving that I'm almost embarrassed to put it here. But long before it was the hallmark of a cultural earthquake/tidal wave that changed everything, etc., blahhh, it was this funny-weird song that a friend turned up on a 45 single. A 45 single! That by itself seemed strange enough at the time. Then it was this. Sure, there's a lot of scary sensation to it, big swaggering words like "anarchy" and "Antichrist" and all that unholy cackling from Johnny Rotten (later John Lydon), and plus he's not such a great singer you know, or anyway misses a lot of notes. But it's as much a pure pop song for now people as anything concocted by Nick Lowe and his Stiff brethren and that's exactly how I took it. I just loved it. Somebody put it on a tape for me, and I dubbed it from there onto all kinds of tapes for other people. I still think it's a pretty swell song, with a big raw wailing guitar sound and martial marching tempos, and all the howling and caterwauling from Lydon. There's something just thrilling about it. "There's so many ways to get what you want!" "It's the only way to be!" And, of course, the one that resonates across the ages, "I wanna destroy!" Each and every with an exclamation point embedded in the grain of the vocals and the emphatic kick of the band. I was perfectly prepared to accept this as the future of rock 'n' roll. I'm still not sure it wasn't, although by the time I was reading about them regularly in fan magazines they were pretty much over. They weren't exactly dead, they still aren't (and that includes poor old Sid). But they were over—an interesting state of affairs that this song utterly embodies, tensions and all.

Wednesday, November 09, 2011

29. Nirvana, "Sliver" (1990)

(listen)

On some level I can understand the reluctance to embrace Nirvana, who stood so obviously on the shoulders of those who had gone before. Never mind that Kurt Cobain himself was all too painfully aware of that. That said, I don't know how anyone denies this pure blast of kid pain and joy, which seems to me to go to the heart of who Cobain was, what he wanted and what he was capable of. It's only a little longer than two minutes but it's pretty much got everything we've come to associate with Nirvana: raw vocals, the exaggerated soft/noisy dynamics, squealing feedback, surprising flashes of melodics, and a certain amount of self-consciousness in the lyrics, which are more straightforward than usual. In fact, it's the lyrics that make it, a story of a kid's night with his grandparents babysitting him while his parents are out on a date. The details are just right: "I kicked and screamed, said please, oh no" and "Had to eat my dinner there / Mashed potatoes and stuff like that / Couldn't chew my meat too good" and "I fell asleep, and watched TV / Woke up in my mother's arms" and, maybe best of all, "Grandma take me home X19." He completely inhabits the world of a seven-year-old, the constant bewildering onrush of overwhelming crises and banal routines disrupted, bicycles and and roast beef, the rapid insensible switch back and forth between terror and fun and peace, all the familiarities that define the boundaries we push against, that hold us in place. In Cobain's case, of course—in many, many cases—the boundaries ultimately gave way, a defining tragedy, or trauma anyway, and in that sense "Sliver" also represents a critical piece in understanding Cobain and Nirvana, and ourselves.

On some level I can understand the reluctance to embrace Nirvana, who stood so obviously on the shoulders of those who had gone before. Never mind that Kurt Cobain himself was all too painfully aware of that. That said, I don't know how anyone denies this pure blast of kid pain and joy, which seems to me to go to the heart of who Cobain was, what he wanted and what he was capable of. It's only a little longer than two minutes but it's pretty much got everything we've come to associate with Nirvana: raw vocals, the exaggerated soft/noisy dynamics, squealing feedback, surprising flashes of melodics, and a certain amount of self-consciousness in the lyrics, which are more straightforward than usual. In fact, it's the lyrics that make it, a story of a kid's night with his grandparents babysitting him while his parents are out on a date. The details are just right: "I kicked and screamed, said please, oh no" and "Had to eat my dinner there / Mashed potatoes and stuff like that / Couldn't chew my meat too good" and "I fell asleep, and watched TV / Woke up in my mother's arms" and, maybe best of all, "Grandma take me home X19." He completely inhabits the world of a seven-year-old, the constant bewildering onrush of overwhelming crises and banal routines disrupted, bicycles and and roast beef, the rapid insensible switch back and forth between terror and fun and peace, all the familiarities that define the boundaries we push against, that hold us in place. In Cobain's case, of course—in many, many cases—the boundaries ultimately gave way, a defining tragedy, or trauma anyway, and in that sense "Sliver" also represents a critical piece in understanding Cobain and Nirvana, and ourselves.

Tuesday, November 08, 2011

30. Love, "My Little Red Book" (1966)

(listen)

There's something so deliciously infectious about this nicely appointed little rave-up. It hooks on right away with a fast-tempo'd nervous high-hat pitter-pat and fine rubbery bass figure and builds up its impossible head of steam so efficiently you're probably not even half aware how good it is until it's over. You have to hear it again, almost immediately, or anyway I always do. It just had to be a surefire hit on the '60s discotheque dance floors. I don't know how it could miss. And it all seems so hit/miss unlikely now too: I get a big kick, first, out of the fact that it's a Burt Bacharach/Hal David song, featured with pipe organ (and too slow!) as recorded by Manfred Mann for the kooky mid-'60s comedy, What's New Pussycat? (written by Woody Allen, starring Peter Sellers, and with Tom Jones turning the title theme into a big hit). How in the world did it ever fall into the orbit of Arthur Lee? I don't even care. I'm just glad it did. Lee and Love were authors of the great album Forever Changes, recommended to anyone who doesn't already know it, but this was from the band's first, self-titled album, appropriately enough kicking it off with this burst of pure sugar rush energy. Speed, speed, speed, haste, haste, haste, the thing just moves. It's got so much propulsive momentum indeed that I almost get nervous when it plays, but the Bacharach melody and composition is as sweet and beguiling as anything he did. If it's an unexpected alliance of pop forces, it's also one that works as well as practically any other out there. Play it play it again, play it again!

There's something so deliciously infectious about this nicely appointed little rave-up. It hooks on right away with a fast-tempo'd nervous high-hat pitter-pat and fine rubbery bass figure and builds up its impossible head of steam so efficiently you're probably not even half aware how good it is until it's over. You have to hear it again, almost immediately, or anyway I always do. It just had to be a surefire hit on the '60s discotheque dance floors. I don't know how it could miss. And it all seems so hit/miss unlikely now too: I get a big kick, first, out of the fact that it's a Burt Bacharach/Hal David song, featured with pipe organ (and too slow!) as recorded by Manfred Mann for the kooky mid-'60s comedy, What's New Pussycat? (written by Woody Allen, starring Peter Sellers, and with Tom Jones turning the title theme into a big hit). How in the world did it ever fall into the orbit of Arthur Lee? I don't even care. I'm just glad it did. Lee and Love were authors of the great album Forever Changes, recommended to anyone who doesn't already know it, but this was from the band's first, self-titled album, appropriately enough kicking it off with this burst of pure sugar rush energy. Speed, speed, speed, haste, haste, haste, the thing just moves. It's got so much propulsive momentum indeed that I almost get nervous when it plays, but the Bacharach melody and composition is as sweet and beguiling as anything he did. If it's an unexpected alliance of pop forces, it's also one that works as well as practically any other out there. Play it play it again, play it again!

Monday, November 07, 2011

31. Joy Division, "Love Will Tear Us Apart" (1980)

As epitaphs go, you're hard put to find many more apt ones to chisel onto the gravestone of Joy Division's much lamented and still missed Ian Curtis, who wrote this song with mates Peter Hook, Stephen Morris, and Bernard Sumner, who would go on—improbably, or so I thought for a long time—to become New Order (and please don't miss the Nazi thematics bridging the two). Curtis poured a lot of himself into this, somehow you just know it even if you don't know who he is or much about him. He even picked up a guitar to play a few chords. I have never found it as ruinously bleak as the first two albums, perhaps because I happened to acquire the single shortly after it was released and spent many weeks and months puzzling over it. As sonics, it strikes an almost impossible balance between robotic and organic, even as it brims with a sadness almost impossible to put one's finger on. It's also catchy as hell, with a melody that sticks good and hard. Often, when I find myself frustrated by something yet compelled anyway to continue worrying it—a particularly knotty anacrostic, say—I have found myself singing cheerily, "There's a taste in my mouth / As desperation takes hold," humming and even whistling. Maybe that's something about me. Joy Division occupies an interesting niche at this juncture, lo these many decades on, at once overrated and underrated. I don't like Closer the way I know so many others do, but I have often been intimate with Unknown Pleasures. And this, from title to tune to verse to chorus, has long been a stone favorite, perfect, and surprisingly so, for so many occasions.

Sunday, November 06, 2011

Back When We Were Grownups (2001)

For anyone who's read much of Anne Tyler there are a number of non-surprises here: the main character, Rebecca Holmes Davitch, is loving, sensitive, nurturing, humorous, expansive, a middle-aged woman who is taken for granted by her family, who maintains a continual air of upbeat enthusiasm and forced gaiety, and who doesn't quite understand how she ended up where she is. Surrounding her are any number of halfway lost ne'er-do-wells, vaguely unpleasant emotional leeches, and self-centered nincompoops who feed casually on her energy (among them her 87-year-old mother). It's arguable that she's happier than she knows, means more to the people in her life than she knows, is richer than George Bailey, etc., etc. But that's at best an even-money bet, I think. The surprise for me in this one was the hard rejection of the typical Tyler fussy person, who is perhaps best personified across her oeuvre by the Leary family in The Accidental Tourist. In this case it's Will Allenby, the boyfriend of Rebecca's youth that she threw over on the way to her present life, which shortly left her a widow responsible for four daughters, only one of them her own—not to mention emotionally responsible for a ragbag collection of characters from her deceased husband's extended family. Rebecca reaches out to Allenby, finding herself in a place where she rues the loss of a relationship that in memory was safe and warm and comfortable. But Allenby, as a tenured academic and aging divorced man, with a daughter with whom he cannot connect, has remarkably few charms. He is like the worst of the Learys with nothing to offset it, disconnected from all around him and deeply delusional about himself and his capabilities, which include at least one frightening episode of losing control and more generally a pathological inability to love and accept love. I had some personal identification with him in spite of all that, and thus his categorical rejection by Rebecca came almost as a shock. I didn't see how it could work out, but Tyler is usually more generous about the way she approaches these things and Rebecca was almost brutal with him. And then Tyler reveals how deeply depressed she actually is, what a blow the loss of her husband decades earlier had been, and how easily the callous disregard of her adopted family can leave her feeling adrift and lost. In many ways this seemed to me a notably depressing novel, rather unusual on the whole for Tyler. It does end on a note of cautious optimism, and I'm pretty sure, reading the tea leaves of interviews with her, that she sees the resolution as much closer to feel-good than I do. It left me feeling, in its immediate glow, a bit gloomy on the whole.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, November 05, 2011

Peter Gabriel (1980)