Saturday, March 31, 2012

Wild Gift (1981)

Any lingering doubts about X—most to that point seemed to inhere most virulently for the ridiculous reason that the band came from Los Angeles—were pretty much atomized once and for all with this second album, which is A) undeniable, B) ferocious, C) instant classic punk-rock, D) a pungent tangle of emotion and defiance, or E) all of the above. (If you don't know the right answer, remember that "B" tends to be the smart guess in multiple-choice tests.) X just never was any ordinary iconic punk-rock band. There was the matter of the Door (that's Ray Manzarek producing again, as he did all of the first four essential albums), the matter of the super fucked-up couple at the center of it, the matter of the guitarist who worshiped Gene Vincent above all others, and, yes, the matter of the geographical location. "What's there to be so mad about?" is the typical stance taken by outsiders towards Los Angeles—much more so then. Anyway, X made it pretty clear what they were so mad about, this rotten old world we're stuck with, with the rest of the losers, perverts, drunks, cheats, frauds, God-shriekers, misers, and toadies. And when that won't do, Exene Cervenka and John Doe always had each other (in these songs forever, though they finally divorced in 1985). I think Cervenka is a better songwriter, and Doe a better singer, than people always remember. Guitar player and rock star Billy Zoom, with D.J. Bonebrake, already one of the great drummers, keep the focus on the roar that must sooner or later erupt out of the skittish, tentative way they approach a song. The rhythm of assault and retreat is steady here, with various modulations in terms of harmony, melody, country flourishes, lyrical thematics. Always it roots itself in elaborations of the staple of rockin' and in that regard it can feel as nutritious as a well-balanced breakfast. It deserves to be played very loud. I should think that goes without saying. With such a sturdy framework and tuned instincts in place, now and then, as on "The Once Over Twice," "In This House That I Call Home," "White Girl," or "When Our Love Passed Out on the Couch," they manage to reach even deeper, go even higher, extend even further. One of my regrets is that I never managed to see them in this period. They sound capable of effortlessly great sets, the kind that always end way too soon.

Friday, March 30, 2012

Rear Window (1954)

USA, 112 minutes

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writers: John Michael Hayes, Cornell Woolrich

Photography: Robert Burks

Music: Franz Waxman

Editor: George Tomasini

Cast: James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Wendell Corey, Thelma Ritter, Raymond Burr, Judith Evelyn, Ross Bagdasarian, Georgine Darcy, Sara Berner, Frank Cady, Jesslyn Fax, Rand Harper, Havis Davenport, Irene Winston

To say that Rear Window is Alfred Hitchcock's greatest gimmick movie, with Rope and Lifeboat and the other examples of his playful formal experimentalism embedded throughout his catalog, is to risk reducing and ghettoizing one of his greatest achievements to its self-imposed constraints—in this case, confining all the action to a small apartment and what can be seen from it. It's not just that Rear Window is a dandy (if inevitably somewhat dated) edge-of-the-seat thriller, but also it's so neatly positioned to explore one of Hitchcock's enduring themes, voyeurism and the simultaneous power and impotence of "the gaze," which we take with us to the movies every time we go.

It shouldn't be surprising how good it is—any number of Hitchcock's greatest strengths are in play. It looks good, sounds good, plays like clockwork. It was made in the '50s, when he was arguably at the peak of his various Hollywood powers. It stars James Stewart, perhaps his greatest alter ego (though I'd be inclined to put Cary Grant just a tetch ahead of him on that score), and Grace Kelly, an archetypal Hitchcock blonde (as with any of them, she is required only to hit her marks and get her lines out and anything else is lagniappe; and stiffness appears to be a plus). You almost don't need to know any more than that. The result is a picture that many flatly single out as his best.

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Writers: John Michael Hayes, Cornell Woolrich

Photography: Robert Burks

Music: Franz Waxman

Editor: George Tomasini

Cast: James Stewart, Grace Kelly, Wendell Corey, Thelma Ritter, Raymond Burr, Judith Evelyn, Ross Bagdasarian, Georgine Darcy, Sara Berner, Frank Cady, Jesslyn Fax, Rand Harper, Havis Davenport, Irene Winston

To say that Rear Window is Alfred Hitchcock's greatest gimmick movie, with Rope and Lifeboat and the other examples of his playful formal experimentalism embedded throughout his catalog, is to risk reducing and ghettoizing one of his greatest achievements to its self-imposed constraints—in this case, confining all the action to a small apartment and what can be seen from it. It's not just that Rear Window is a dandy (if inevitably somewhat dated) edge-of-the-seat thriller, but also it's so neatly positioned to explore one of Hitchcock's enduring themes, voyeurism and the simultaneous power and impotence of "the gaze," which we take with us to the movies every time we go.

It shouldn't be surprising how good it is—any number of Hitchcock's greatest strengths are in play. It looks good, sounds good, plays like clockwork. It was made in the '50s, when he was arguably at the peak of his various Hollywood powers. It stars James Stewart, perhaps his greatest alter ego (though I'd be inclined to put Cary Grant just a tetch ahead of him on that score), and Grace Kelly, an archetypal Hitchcock blonde (as with any of them, she is required only to hit her marks and get her lines out and anything else is lagniappe; and stiffness appears to be a plus). You almost don't need to know any more than that. The result is a picture that many flatly single out as his best.

Wednesday, March 28, 2012

Pulp, "Common People" (1995)

(listen)

Class warfare! Jarvis Cocker and mates, from across the Atlantic Ocean, craft a theme song for the eternal verities of the rich, but I'm not sure a good many people know about it even yet. I found out because a couple of my hipster pals were onto Pulp and Jarvis Cocker and Different Class. Otherwise I don't think it ever escaped far from the dance clubs of the UK until William Shatner came along and broke down the lyrics so starkly via the simple expedient of enunciating them clearly. So if I never exactly cottoned to the fine bent of the lyrics for many years, it wasn't like I noticed anything missing. This is a terrific song. I listened to the album on a daily basis for several weeks and have pulled it out since and it always sounds good, and so does this song, which is rousing and alive, throbbing and knowing, the kind of thing you might want to stand on a chair for and play loud. At six minutes it's got all the imposing presence of a dance song, and it's insinuating and physical in its attack, but it's also traditional verse-chorus-verse pop. Try it this way: Should we be surprised that Pitchfork a couple of years ago put it at #2 on their list of Top 200 Tracks of the '90s? Oh, right, and this: Cocker's reading of the lyrics is just fine, now that I know to hold off on all my flailing and kinetic pleasure and pay closer attention. His cartoon-dog Smedley way of sidling in with his croaking baritone may be almost soporific in the middle of all this gorgeous din, but once you know to follow along, why damn, hell, he's telling the story just as good as Captain Kirk too. It's caustic, biting, and very funny.

Class warfare! Jarvis Cocker and mates, from across the Atlantic Ocean, craft a theme song for the eternal verities of the rich, but I'm not sure a good many people know about it even yet. I found out because a couple of my hipster pals were onto Pulp and Jarvis Cocker and Different Class. Otherwise I don't think it ever escaped far from the dance clubs of the UK until William Shatner came along and broke down the lyrics so starkly via the simple expedient of enunciating them clearly. So if I never exactly cottoned to the fine bent of the lyrics for many years, it wasn't like I noticed anything missing. This is a terrific song. I listened to the album on a daily basis for several weeks and have pulled it out since and it always sounds good, and so does this song, which is rousing and alive, throbbing and knowing, the kind of thing you might want to stand on a chair for and play loud. At six minutes it's got all the imposing presence of a dance song, and it's insinuating and physical in its attack, but it's also traditional verse-chorus-verse pop. Try it this way: Should we be surprised that Pitchfork a couple of years ago put it at #2 on their list of Top 200 Tracks of the '90s? Oh, right, and this: Cocker's reading of the lyrics is just fine, now that I know to hold off on all my flailing and kinetic pleasure and pay closer attention. His cartoon-dog Smedley way of sidling in with his croaking baritone may be almost soporific in the middle of all this gorgeous din, but once you know to follow along, why damn, hell, he's telling the story just as good as Captain Kirk too. It's caustic, biting, and very funny.

Tuesday, March 27, 2012

Heavenly Creatures (1994)

#42: Heavenly Creatures (Peter Jackson, 1994)

Peter Jackson knows his way around moviemaking, and he certainly has range, but too often his interests land wide of the mark of my own. I appreciate the capacity for joke-gore that he demonstrated early in his career with Bad Taste and Braindead, over-the-top exercises that rival even Sam Raimi's. But the joke wears thin. And while his Lord of the Rings trilogy is magnificent as can be, it doesn't quite transcend the literary property on which it's based, something with which I never quite connected even though I slogged all the way through it as a teen.

That makes Heavenly Creatures something of the Baby Bear for me of his catalog: juuust riiight. It relies as much as anything of his on the flights of fancy of which he's so capable, slipping occasionally into gorgeous eye-candy visions that feel as if they veer close to psychotic breaks, and churning always with an unholy energy and exuberance. The story, "based on real events," recounts an intense friendship between two adolescent girls that takes a turn for the unhealthy. Starring Melanie Lynskey and Kate Winslet, both in debut performances, it travels deep into the darkest heart of the relationship. The clip at the link, which features a Mario Lanza song, gives some indication of what Jackson is managing here, most impressively finding ways to avoid sexualizing the whole thing, even when the girls spontaneously start tossing away their clothes. It's a temptation that would have been way too hard to resist for many a filmmaker, I suspect (and an interpretation of the film that some still see, wrongly I think). The ending, which leaves behind all pretense of fantasy and turns instead to jarring cuts and a gritty handheld-camera verite, is devastating (if you're so inclined you can relive it here, complete with the Puccini preamble that sets it up so well; parental warning).

Peter Jackson knows his way around moviemaking, and he certainly has range, but too often his interests land wide of the mark of my own. I appreciate the capacity for joke-gore that he demonstrated early in his career with Bad Taste and Braindead, over-the-top exercises that rival even Sam Raimi's. But the joke wears thin. And while his Lord of the Rings trilogy is magnificent as can be, it doesn't quite transcend the literary property on which it's based, something with which I never quite connected even though I slogged all the way through it as a teen.

That makes Heavenly Creatures something of the Baby Bear for me of his catalog: juuust riiight. It relies as much as anything of his on the flights of fancy of which he's so capable, slipping occasionally into gorgeous eye-candy visions that feel as if they veer close to psychotic breaks, and churning always with an unholy energy and exuberance. The story, "based on real events," recounts an intense friendship between two adolescent girls that takes a turn for the unhealthy. Starring Melanie Lynskey and Kate Winslet, both in debut performances, it travels deep into the darkest heart of the relationship. The clip at the link, which features a Mario Lanza song, gives some indication of what Jackson is managing here, most impressively finding ways to avoid sexualizing the whole thing, even when the girls spontaneously start tossing away their clothes. It's a temptation that would have been way too hard to resist for many a filmmaker, I suspect (and an interpretation of the film that some still see, wrongly I think). The ending, which leaves behind all pretense of fantasy and turns instead to jarring cuts and a gritty handheld-camera verite, is devastating (if you're so inclined you can relive it here, complete with the Puccini preamble that sets it up so well; parental warning).

Sunday, March 25, 2012

52 Pick-Up (1974)

52 Pick-Up is Elmore Leonard's 11th novel but most of those before this—inimitably Leonard as they may be—had been Westerns, and here he is still feeling his way into various particulars of the suspense/thriller crime genre. He's not always on his game entirely, but I still count it as one of my favorites, with 1980's City Primeval, perhaps because there's something of the energy of discovery to it (or perhaps because they are the first two I read). Maybe it's my imagination, but I get a stronger sense here than usual that he is positively relishing the work of pungently capturing the textures and feel of Detroit in the early '70s, with the bad actors going casually day to day dealing drugs, porn, call girls, grand theft auto, basically whatever it takes. As always, one of the bad actors is very, very bad. It must be fun to dream these guys up and send them on their rounds. Here it's a blackmailing plot by a trio of ne'er-do-wells that morphs into an episode of kidnap and appalling treatment of our hero's wife—even as our hero, a Vietnam vet natch, coolly plays the bad guys off one another like a chess master up against the whole town at the local library on a Saturday afternoon. The wife even gets a supporting role as typical flinty, clipped-speech Leonard hero too, and that may be the kindest thing Leonard gives us in regard to her once the mayhem is fully engaged and events are unfolding like fate. Leonard actually has two great gifts, which are related but don't often enough come together. First, what he's famous for, his language is so refined and boiled down it is virtually transparent and so fun to read that at points I find myself laughing out loud at how good it is. Second, he knows how to structure a plot. He doesn't concern himself overly with anything new—criminy, he started out writing Westerns, perhaps the most conservative of all the literary genres, and they're all pretty conservative. Leonard's stock-in-trade tends toward some combination of revenge plot and damsel-in-distress. But the way he picks up the cards, shuffles them, and deals—he's always finding a new direction to come at you, and more often than not you never see it coming. I can't think of any better place to start or finish with Leonard than right here. Go ahead, you can skip a night of sleep.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, March 24, 2012

Tropical Brainstorm (2000)

The late Kirsty MacColl, who died in a boating accident the same year her fifth and final (and best, as far as I can tell) album was released, may be best remembered now either for singing on the Pogues' "Fairytale of New York" or for being married to producer Steve Lillywhite. The only thing you might learn about her from either of those items is her pluck, of which there was plenty. Other things you should understand: she knows her way around a pop song, and she can be very funny when she has a mind, as she does here, and often. It's mostly tossed-off gesture and gags, which is no surprise because she also had some luck as a comic actor on British TV and knew how to do it. And she really did know how to do it, slyly embedding a good deal of it in the throwaways, plumbing layers of meaning and quickly moving on. For example, I don't think there's anyone alive or dead who could ever match her reading of the line, "I've got a powerful horse outside," which only becomes more funny the more times I hear it—and notice it—sitting there in the song "In These Shoes?" Sometimes, as on that self-same song, she does flirt dangerously close to shtick, but that comes with the territory of someone trying so hard, and with so much good creative energy, to provoke both laughs and tears. She shuttles back and forth between both ends of the spectrum even as she sticks close to what she's best at, working an everywoman's various takes on fashion, men, sex, fun, and sadness. She's fearless and never stops trying things. She draws heavily for many songs from Cuban, Brazilian, and other Latin musical sources, which indeed is the album's most distinguishing feature for many (e.g., Christgau), and certainly keeps the set crackling with energy. She entertains elements of sadomasochism and boo-hoos about tiny failed relationships in ways I had only heard before in conversation, not song. And she "goes there" in "Here Comes That Man Again," goofing on cybersex and the niceties, though the modem sound effects now serve to put it all in the vicinity of quaint. "Celestine" is the song that sold me on her once and for all, a meditation on alter egos that is effortlessly natural, closely observed, and resonant. This is a pretty big album too, nearly an hour long with 16 tracks—many rooms in the mansion. Worth spending time in nearly all of them.

Friday, March 23, 2012

4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007)

4 luni, 3 saptamâni si 2 zile, Romania/Belgium, 113 minutes

Director: Cristian Mungiu

Writers: Cristian Mungiu, Razvan Radulescu

Photography: Oleg Mutu

Editor: Dana Bunescu

Cast: Anamaria Marinca, Laura Vasiliu, Vlad Ivanov, Alex Potocean, Luminita Gheorghiu, Ioan Sapdaru

This small-scale and ferociously intense story of late-period Communism, determinedly minute in scope and set in 1987 Romania towards the end of the harsh regime of Nicolae Ceausescu, made such a terrific impact on me the first time I saw it that I wasn't sure I wanted to see it again any time soon. When I finally did return to it recently I was interested to see just how much the sophistication of its aesthetics contributed to my first experience—and how carefully and deliberately the whole thing is put together.

The premise is so simple it feels almost cold in its calculation (and yo heads up spoilers begin now). Gabita (played by Laura Vasiliu) is pregnant and needs an abortion, which is illegal. She enlists her fellow student, roommate, and friend Otilia (played by Anamaria Marinca with a disaffected nonchalance that is often brilliant) to help her. The entire picture is a chronicle of their efforts to accomplish this on the day set for it—borrow the rest of the money they expect they will have to pay, connect with the abortionist, find a hotel room in which the procedure can take place, dispose of the fetus, and so on. All of this is set against a stifling inertia of bureaucracy and queasy numb apathy that hovers ineffably and penetrates all, like miasma in a swamp.

Director: Cristian Mungiu

Writers: Cristian Mungiu, Razvan Radulescu

Photography: Oleg Mutu

Editor: Dana Bunescu

Cast: Anamaria Marinca, Laura Vasiliu, Vlad Ivanov, Alex Potocean, Luminita Gheorghiu, Ioan Sapdaru

This small-scale and ferociously intense story of late-period Communism, determinedly minute in scope and set in 1987 Romania towards the end of the harsh regime of Nicolae Ceausescu, made such a terrific impact on me the first time I saw it that I wasn't sure I wanted to see it again any time soon. When I finally did return to it recently I was interested to see just how much the sophistication of its aesthetics contributed to my first experience—and how carefully and deliberately the whole thing is put together.

The premise is so simple it feels almost cold in its calculation (and yo heads up spoilers begin now). Gabita (played by Laura Vasiliu) is pregnant and needs an abortion, which is illegal. She enlists her fellow student, roommate, and friend Otilia (played by Anamaria Marinca with a disaffected nonchalance that is often brilliant) to help her. The entire picture is a chronicle of their efforts to accomplish this on the day set for it—borrow the rest of the money they expect they will have to pay, connect with the abortionist, find a hotel room in which the procedure can take place, dispose of the fetus, and so on. All of this is set against a stifling inertia of bureaucracy and queasy numb apathy that hovers ineffably and penetrates all, like miasma in a swamp.

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

David Bowie, "V-2 Schneider" (1977)

(listen)

This is one of only a few of the experimental-style soundscapes hatched by David Bowie and Brian Eno on Low and "Heroes" that I can actually say I much care for. More often, occupying the side 2s of their first two collaborations, I think the exercises lose focus, wallowing along in their own vapors, though certainly concentrated effort can provide its rewards, as it always does when one wants it to. But this song, which kicks off the second side of "Heroes," is pretty much undeniable. All in the thick of the collaborators' incoherent embrace of Berlin and the Cold War as existential moral imperative—highly alluring in its specific historical moment, but nonsensical—it has always leaped right off the album for me, soaring like Thomas Pynchon's language. The love of Bowie (more than Eno, I suspect) for all things Berlin extends ever so delicately into ... what? "Schneider" is not just the last name of a Kraftwerk principal, after all, but also a maneuver intended to prevent an opponent from scoring a point, and the V-2 rocket is what rained down on London. But never mind that. Washed through in layers of rocket screams and the static found between radio and television stations, this mostly instrumental track (there's various humming and some singing of the title) rides a rhythm section pattern of sure-footed bass and little snare-drum figures, lets its layers pile high on one another, gets soulful with a sax, coalesces on lovely fragments of melody, throbs, aches, swoons, and briefly flares into gray widescreen before tailing away back into oblivion, all of it accomplished once again in just over three minutes. Meet the new pop song.

This is one of only a few of the experimental-style soundscapes hatched by David Bowie and Brian Eno on Low and "Heroes" that I can actually say I much care for. More often, occupying the side 2s of their first two collaborations, I think the exercises lose focus, wallowing along in their own vapors, though certainly concentrated effort can provide its rewards, as it always does when one wants it to. But this song, which kicks off the second side of "Heroes," is pretty much undeniable. All in the thick of the collaborators' incoherent embrace of Berlin and the Cold War as existential moral imperative—highly alluring in its specific historical moment, but nonsensical—it has always leaped right off the album for me, soaring like Thomas Pynchon's language. The love of Bowie (more than Eno, I suspect) for all things Berlin extends ever so delicately into ... what? "Schneider" is not just the last name of a Kraftwerk principal, after all, but also a maneuver intended to prevent an opponent from scoring a point, and the V-2 rocket is what rained down on London. But never mind that. Washed through in layers of rocket screams and the static found between radio and television stations, this mostly instrumental track (there's various humming and some singing of the title) rides a rhythm section pattern of sure-footed bass and little snare-drum figures, lets its layers pile high on one another, gets soulful with a sax, coalesces on lovely fragments of melody, throbs, aches, swoons, and briefly flares into gray widescreen before tailing away back into oblivion, all of it accomplished once again in just over three minutes. Meet the new pop song.

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

Cabaret (1972)

#43: Cabaret (Bob Fosse, 1972)

As someone in possession of a post-Elvis rock sensibility, I often find it hard to understand the case for musicals—or that's the impression I generally have of myself. But looking at my list I see it's scattered with movies that fit the bill all too well. Cabaret is something of an anti-musical, similar to other projects of the time, anti-westerns, anti-romances, etc. (This all in the wake of Bonnie and Clyde, which changed so many things.) Director/choreographer Bob Fosse deliberately adapts a property that places the action in Berlin in one of the darkest years of German history, 1931, and makes the rise of Nazism a central feature of the story. Ironically, Hollywood musicals of that very same era—1933's Footlight Parade, for example, a Busby Berkeley picture—were doing pretty much the same thing, acknowledging the dreary tenor of the times and the hope for escape from it that song and dance and illicit activity provided.

But Cabaret is a '70s picture, not a '30s picture, and its sense of "divine decadence" comes more figuratively out of David Bowie and Los Angeles than Alfred Doblin and Berlin. It's no less thrilling for that. Fosse's dance numbers are as sharp as they can be, it's Liza Minnelli's great moment and best performance ever, Joel Grey is the secret ingredient all through, and the story comes with a surprising number of nicely handled complexities.

As someone in possession of a post-Elvis rock sensibility, I often find it hard to understand the case for musicals—or that's the impression I generally have of myself. But looking at my list I see it's scattered with movies that fit the bill all too well. Cabaret is something of an anti-musical, similar to other projects of the time, anti-westerns, anti-romances, etc. (This all in the wake of Bonnie and Clyde, which changed so many things.) Director/choreographer Bob Fosse deliberately adapts a property that places the action in Berlin in one of the darkest years of German history, 1931, and makes the rise of Nazism a central feature of the story. Ironically, Hollywood musicals of that very same era—1933's Footlight Parade, for example, a Busby Berkeley picture—were doing pretty much the same thing, acknowledging the dreary tenor of the times and the hope for escape from it that song and dance and illicit activity provided.

But Cabaret is a '70s picture, not a '30s picture, and its sense of "divine decadence" comes more figuratively out of David Bowie and Los Angeles than Alfred Doblin and Berlin. It's no less thrilling for that. Fosse's dance numbers are as sharp as they can be, it's Liza Minnelli's great moment and best performance ever, Joel Grey is the secret ingredient all through, and the story comes with a surprising number of nicely handled complexities.

Sunday, March 18, 2012

Maus: A Survivor's Tale (1973-1991)

It seems like every time I go through the two little volumes of Maus it finds new ways to surprise me. This most recent time the core story reached me in ways it never has. Vladek Spiegelman, a Polish Jew and father of the author and illustrator, Art, actually spent most of his time during World War II and the run-up surviving one way and another on his own. He was not finally caught and sent to Auschwitz until 1944. Until then he lived by his wits, courage, and a good deal of luck. The realities of his life are all but unimaginable to me now—even to his son who created this, which of course contributes to its complexity and makes it so fascinating. In many ways, Vladek is an awful human being, and Art his ungrateful heir. But in just as many ways they are both admirable—and likeable. The art struck me as surprisingly crude this time, even stick-man simple at points, and generally much more so than I had remembered, but the story is always compelling, and many of the features of the art serve their purposes well. It always works, and some panels are amazing; this time I really noticed the way the Jews (as mice) are shown enduring pain. It's simple, yet haunting, neck tipped back and open mouth a hollow black. This last time through I tried to put myself in Vladek's place. Essentially he spent his 30s, the better part of a full decade, feeling the increasingly dire impact of the German Nazi regime on his life. I suspect I would have been among those who didn't survive—so much of the hiding and running and the humiliations endured seem to me simply intolerable. But you never know, and in many ways that's explicitly Vladek's message to the rest of us, mediated by Art. Vladek's wife (Art's mother), Anja, was weak like me but she made it, even though much of the rest of both her and Vladek's families, including their first son (Art's older brother, whom Art never met), did not. But then she committed suicide in 1968 with no explanation. "No note!" Vladek and Art both can't help but pointing out repeatedly. Aside from its undeniable place as an important milestone of the graphic novel, Maus deserves all its many accolades and its reputation for finding a way to tell a familiar story that makes it uniquely compelling and more powerful than ever. Someone else has no doubt made the point somewhere: this deserves a place among the greatest works of the 20th century, and it certainly deserves to be read, discussed, and taught everywhere.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, March 17, 2012

Abraxas (1970)

Big difference between the first Santana album and this one, such to me that it sounds on the order of the before-and-after of a trip to the crossroads. Again, I'm pretty sure most of that is the production, with the raw vitality of the mush that preceded it sculpted with definition, texture, and grace. For one thing, this catapulted Carlos Santana to nearly the top of the list of my favorite guitar players at the time, with Duane Allman and Jimi Hendrix. Santana is the most lyrical and eloquent of them, the most oriented to sensual pleasure. This might be most evident on the instrumental "Samba Pa Ti," whose signature melody is a swooning, bruised thing, which likely any novice player with a bit of concentration could pick out and play just as well. Aye but there's the rub, they didn't now did they? Not to mention there's no way anyone else ever takes it the places he does anyhow. I appreciate a player who can wield silence and emptiness as well as bring the tumbling noise and the melody too; I can check all that off my list here. Also, Carlos Santana always somehow manages to sound impossibly suave and debonair for what he is doing, so bonus. The same basic steamrolling unit from that first album keeps a lively throughline going, enough so that at least a couple of these tracks just jettison the singing altogether, while others keep it to a minimum. There's even a few more percussionists than before, which only means the thunder is denser when deployed—here they know better when to lay back and let the songcraft do the work. This remains my favorite from the long and estimable catalogue of Santana (the band), which has its gems but too often requires a lot of work to dig them out, as the siren call of prog beckoned for them next. Eventually the same impulse to better production values that makes this album work so well started to take on a life of its own, as it does with so many seduced by prog, and the results too often strayed toward the arid and sterile. Not only are none of those problems here, I don't particularly hear even a hint of them. Thus this has become the Santana album to which I most easily and frequently—and happily—return.

Friday, March 16, 2012

Andrei Rublev (1966)

Andrey Rublyov, USSR, 205 minutes

Director: Andrey Tarkovskiy

Writers: Andrey Konchalovskiy, Andrey Tarkovskiy

Photography: Vadim Yusov

Music: Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov

Editors: Lyudmila Feiginova, Olga Shevkunenko, Tatyana Yegorychyova

Cast: Anatoli Solonitsyn, Ivan Lapikov, Nikolai Grinko, Nikolai Sergeyev, Irma Raush, Nikolai Burlyayev, Yuri Nazarov

A friend of mine tends to be deeply suspicious of biopics for their rote recitations of all too familiar events and the distorting constrictions they impose: too much focus on one person, too many compressions to turn an entire lifetime into a two-hour narrative, too much temptation for hagiography, and too much reliance on the performance of a single player to make them work (and the performances, such as Meryl Streep's recent turn in The Iron Lady, often have the further hazard of feeling more like stunts and/or extended impressions).

It occurred to me that Andrei Rublev could well be the exception. Technically, it's a biopic, but it finds any number of ways to break the mold, starting with its imposing size, well north of three hours. The current Criterion DVD bears the "director's cut," which is about as long as Seven Samurai or The Godfather: Part II—requiring a commitment and your best iron butt. For many years after its release it played in a version closer to 180 minutes, after cuts were made by director and writer Andrei Tarkovsky based on requirements of Soviet censors (although Tarkovsky later defended the shorter versions, which he also personally endorsed, particularly a 186-minute cut). So, yes, folks, in short, it's another case of a widely hailed critical masterpiece of world cinema that comes with its own competing versions to sort through (after finding).

And, as with Children of Paradise, The Passion of Joan of Arc, or The Rules of the Game, it also has a troubled production/distribution history, which in this case was mostly caused by the Soviet government of the time, mired in the depths of the Cold War in the '60s and '70s. For many years tracking down and seeing Andrei Rublev was no easy matter.

Director: Andrey Tarkovskiy

Writers: Andrey Konchalovskiy, Andrey Tarkovskiy

Photography: Vadim Yusov

Music: Vyacheslav Ovchinnikov

Editors: Lyudmila Feiginova, Olga Shevkunenko, Tatyana Yegorychyova

Cast: Anatoli Solonitsyn, Ivan Lapikov, Nikolai Grinko, Nikolai Sergeyev, Irma Raush, Nikolai Burlyayev, Yuri Nazarov

A friend of mine tends to be deeply suspicious of biopics for their rote recitations of all too familiar events and the distorting constrictions they impose: too much focus on one person, too many compressions to turn an entire lifetime into a two-hour narrative, too much temptation for hagiography, and too much reliance on the performance of a single player to make them work (and the performances, such as Meryl Streep's recent turn in The Iron Lady, often have the further hazard of feeling more like stunts and/or extended impressions).

It occurred to me that Andrei Rublev could well be the exception. Technically, it's a biopic, but it finds any number of ways to break the mold, starting with its imposing size, well north of three hours. The current Criterion DVD bears the "director's cut," which is about as long as Seven Samurai or The Godfather: Part II—requiring a commitment and your best iron butt. For many years after its release it played in a version closer to 180 minutes, after cuts were made by director and writer Andrei Tarkovsky based on requirements of Soviet censors (although Tarkovsky later defended the shorter versions, which he also personally endorsed, particularly a 186-minute cut). So, yes, folks, in short, it's another case of a widely hailed critical masterpiece of world cinema that comes with its own competing versions to sort through (after finding).

And, as with Children of Paradise, The Passion of Joan of Arc, or The Rules of the Game, it also has a troubled production/distribution history, which in this case was mostly caused by the Soviet government of the time, mired in the depths of the Cold War in the '60s and '70s. For many years tracking down and seeing Andrei Rublev was no easy matter.

Wednesday, March 14, 2012

David Bowie, "Queen Bitch" (1971)

(listen)

David Bowie calls out Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol by name elsewhere on the 1971 Hunky Dory album, but on "Queen Bitch," buried in the middle of the vinyl LP side 2, he more circumspectly absorbs the anthemic Velvet Underground from "I'm Waiting for the Man" through "Sweet Jane," setting guitarist Mick Ronson loose to rampage. Forty years later it sounds like history being made. Ronson does not let us down: he is efficient, sassy, economical, and brilliant, from the stuffed-up textures of his chords to the way he makes them move to the ease with which he switches over and peals off riffs. This has always been the rockin'est track on what is otherwise essentially a folk-rock album, though one with the future unmistakably stitched into its DNA, busy carrying glam-rock to term, as we see now. "Queen Bitch" is the lark, the place to vent energy; it's also where everything collapsed and crystallized into a vision of sound that would echo through T. Rex, Mott the Hoople, Slade, and a few hundred more. The song appears to be there on the album simply for the pleasure and the kick of cutting loose and somehow it became the embodiment of everything, spidery and nimble, caustic and gossipy, high-pitched with a bottom that moves like cartoon zoo animals, reveling in its outré even as it signals its limits, shrugs its shoulders, plays on. It leaps fully formed and wants to take you for a dance. It doesn't care how you dress, it's going to laugh at the way you dress. You can move or you can stand still in awe of it. Up to you.

David Bowie calls out Bob Dylan and Andy Warhol by name elsewhere on the 1971 Hunky Dory album, but on "Queen Bitch," buried in the middle of the vinyl LP side 2, he more circumspectly absorbs the anthemic Velvet Underground from "I'm Waiting for the Man" through "Sweet Jane," setting guitarist Mick Ronson loose to rampage. Forty years later it sounds like history being made. Ronson does not let us down: he is efficient, sassy, economical, and brilliant, from the stuffed-up textures of his chords to the way he makes them move to the ease with which he switches over and peals off riffs. This has always been the rockin'est track on what is otherwise essentially a folk-rock album, though one with the future unmistakably stitched into its DNA, busy carrying glam-rock to term, as we see now. "Queen Bitch" is the lark, the place to vent energy; it's also where everything collapsed and crystallized into a vision of sound that would echo through T. Rex, Mott the Hoople, Slade, and a few hundred more. The song appears to be there on the album simply for the pleasure and the kick of cutting loose and somehow it became the embodiment of everything, spidery and nimble, caustic and gossipy, high-pitched with a bottom that moves like cartoon zoo animals, reveling in its outré even as it signals its limits, shrugs its shoulders, plays on. It leaps fully formed and wants to take you for a dance. It doesn't care how you dress, it's going to laugh at the way you dress. You can move or you can stand still in awe of it. Up to you.

Tuesday, March 13, 2012

Once (2006)

#44: Once (John Carney, 2006)

I was pleased to see last night that ongoing experiments rolling out advance word of my picks via the medium of powerful psychic vibrations have finally led to an instance of success. I salute Dave MacIntosh, who appears to be an authentic sensitive whether he knew it or not.

I have three movies on my list from the past 10 years, and am only entirely certain about one of them. This is not that one, but I sure like it a lot. It seems to get classified most often as a musical, but it's a musical in about the same way that the double-album Tommy is an opera. Set in Dublin, featuring a street busker with a recently broken heart who meets a Czech émigré barely getting by, it's steeped in a kind of rock culture that traces back to an era of nascent '60s exhaustion, as when Bob Dylan and the Band were down in a basement woodshedding. It's far more Richard Thompson than The Commitments, try it that way. But that's not right either because these songwriters and musicians are more plugged into all the lilting beauties of a romance, so keep that in mind too.

I was pleased to see last night that ongoing experiments rolling out advance word of my picks via the medium of powerful psychic vibrations have finally led to an instance of success. I salute Dave MacIntosh, who appears to be an authentic sensitive whether he knew it or not.

I have three movies on my list from the past 10 years, and am only entirely certain about one of them. This is not that one, but I sure like it a lot. It seems to get classified most often as a musical, but it's a musical in about the same way that the double-album Tommy is an opera. Set in Dublin, featuring a street busker with a recently broken heart who meets a Czech émigré barely getting by, it's steeped in a kind of rock culture that traces back to an era of nascent '60s exhaustion, as when Bob Dylan and the Band were down in a basement woodshedding. It's far more Richard Thompson than The Commitments, try it that way. But that's not right either because these songwriters and musicians are more plugged into all the lilting beauties of a romance, so keep that in mind too.

Sunday, March 11, 2012

The Discomfort Zone (2006)

It's interesting that Jonathan Franzen's last book before this one, How to Be Alone, is billed as a collection of essays whereas this is called a memoir, because they are put together in very similar ways, as collections of stand-alone personal essays, most of them published previously (though often reworked for the books). I think of Franzen as a careful and thoughtful writer so I imagine he has his reasons for distinguishing them as he does—or perhaps that's the publisher's choice, concerned that consecutive collections of essays might be commercial poison for the bestselling hipster author, and Franzen didn't see it as worth the fight. Whatever the case, they are both eminently readable, interesting, and a pleasure, and my only complaint about The Discomfort Zone, if it's even properly a complaint, is that it's too slender, with only six pieces occupying less than 200 pages. This is not tell-all straightforward autobiography proceeding in linear fashion from first memory to final thoughts. Instead Franzen finds poignant periods in his life and lets himself dwell there, moving episodically and feeling his way to various conclusions but more concerned, as always, with the rush and confusion of the sensory impact around him and his own tentativeness and fatal hesitations in embracing experience and attempting to understand and judge it. If you've read anything by Franzen you know who he is; there's just more of that here. Yet in many ways, and I think this is the real value of both How to Be Alone and The Discomfort Zone, everything you think Franzen is he is not. I do think the novels are the place to start—notably The Corrections and Freedom. As much as Franzen indulges a glum ponderous side, his real métier is narrative, where his points are cunningly embedded in characters and their relations to one another and the choices they make. Because it's his métier he doesn't stray far from it in the essays here, which as much as they may be based on factual events are ultimately structured as brooding stories centered on Christian youth fellowship rites, literature and sex, marriage, birds, the alarming drifts of public policy, and all the usual things that preoccupy him. You are likely to find small surprises and overturned expectations even as it confirms in larger terms the person you know, plus it's useful to get some of the background data right from his point of view. In the end, if you get this far, you'll likely be sorry too that it's not even 200 pages.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, March 10, 2012

Santana (1969)

This is probably among the first 15 or 20 albums I bought and for the life of me I wish I could remember the appeal. I know I played it frequently. But it all sounds a bit monochromatic now, sludgy and drony with poor definition inside the hammering fog of sound. With Abraxas, Carlos Santana stepped forward and staked his claim as a lead guitarist. Here he's much more lost in the thundering din of the mix, mostly instrumentals all decked out with one drumkit plus two more percussionists, and a rich, droning, churchy organ. It's more democratic that way but it does tend toward producing a mush. As for the hit, "Evil Ways," I have no explanation for how it became a top 10 hit in early 1970, except for the feeble point that it was early 1970. I remember liking it, but it sounds very bland to me now, and obnoxious when I pay attention to the lyrics. A lot of the material here is bland, there I said it, which I think is a matter of the airless production before anything else. The performances sound worthy and I can imagine myself caught up in the heat of them. The big side-closers from the original vinyl LP, "Jingo" and "Soul Sacrifice," which account for 11 minutes between them, are rousing and energized. One can always hear there's a lot of enthusiasm even if it doesn't always exactly reach one. Now that I think of it, I bet a good deal of my appreciation way back was that there is a potent feeling here of live performance (one reason the Woodstock tracks added for later editions fit so well). I used to love that about live albums when I was 13 and 14 and 15—I even liked stage announcements, having never seen a show until I was nearly 16. By today's standards this debut album is pretty muddy business for something with such an evidently sophisticated rhythmic attack. Again, a problem of the production—and since the producers are Carlos himself and Brent Dangerfield, there's no one else to blame. I'm going to guess they just didn't know their way very well around a studio. I do like the optical illusion puzzle of the cover illustration. I owned the album for weeks or months before I saw anything but the lion. Also, the title alone of one of the later adds, "Fried Neck Bones and Some Home Fries," has to count for something.

Friday, March 09, 2012

Dear Zachary (2008)

(This is also my contribution to the Movie Morality Blogathon, March 6-14, at Checking on My Sausages.)

Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father, USA, 95 minutes, documentary

Director/writer/photography/music/editor: Kurt Kuenne

Dear Zachary roots itself with ease and confidence inside the true-crime subgenre of documentary filmmaking, where all talk sooner or later focuses inevitably, and naturally enough, on "evil" and "justice." I say "naturally enough" because the impulse and point of view in these cases always seems to come from an emotional space still reeling from shock, virtually bludgeoned into a state of incomprehension, one that still seeks and indeed gropes and flails for ways to make sense of insensible events. Implicitly, by true-crime conventions, we are expected to trust the morality of victims ipso facto, when all that's left to them, practically, are the two aching desires: first, to understand (hence "evil" because such events are otherwise impossible to grasp), and second, in addressing the morality, the need to set things right again, back to the way they were, which is equally impossible but is nevertheless the driving impulse behind the continual talk of "justice" and "closure"—neither of which happens, as surviving crime victims say again and again, even when criminals are caught and punished.

Filmmaker Kurt Kuenne has to take his place here as a true-crime documentarian to reckon with, not because he has made such an intensely personal film, with his sad, grieving, outraged personality occupying every square millimeter of every frame. That would itself make sense when a person of some talent and skill directs, writes, shoots, scores, and edits the story of the murder of his childhood best friend, and everything proceeding from the crime. But when the story is full of the kinds of twists and turns no one can make up, with each development more dramatic and astonishing than the last, with copious examples of perverse human behavior operating at multiple levels—that's the domain of the true-crime documentary. It's also the reason I had better warn of spoilers ahead if you don't know this story, whose details are best understood via the picture.

Dear Zachary: A Letter to a Son About His Father, USA, 95 minutes, documentary

Director/writer/photography/music/editor: Kurt Kuenne

Dear Zachary roots itself with ease and confidence inside the true-crime subgenre of documentary filmmaking, where all talk sooner or later focuses inevitably, and naturally enough, on "evil" and "justice." I say "naturally enough" because the impulse and point of view in these cases always seems to come from an emotional space still reeling from shock, virtually bludgeoned into a state of incomprehension, one that still seeks and indeed gropes and flails for ways to make sense of insensible events. Implicitly, by true-crime conventions, we are expected to trust the morality of victims ipso facto, when all that's left to them, practically, are the two aching desires: first, to understand (hence "evil" because such events are otherwise impossible to grasp), and second, in addressing the morality, the need to set things right again, back to the way they were, which is equally impossible but is nevertheless the driving impulse behind the continual talk of "justice" and "closure"—neither of which happens, as surviving crime victims say again and again, even when criminals are caught and punished.

Filmmaker Kurt Kuenne has to take his place here as a true-crime documentarian to reckon with, not because he has made such an intensely personal film, with his sad, grieving, outraged personality occupying every square millimeter of every frame. That would itself make sense when a person of some talent and skill directs, writes, shoots, scores, and edits the story of the murder of his childhood best friend, and everything proceeding from the crime. But when the story is full of the kinds of twists and turns no one can make up, with each development more dramatic and astonishing than the last, with copious examples of perverse human behavior operating at multiple levels—that's the domain of the true-crime documentary. It's also the reason I had better warn of spoilers ahead if you don't know this story, whose details are best understood via the picture.

Wednesday, March 07, 2012

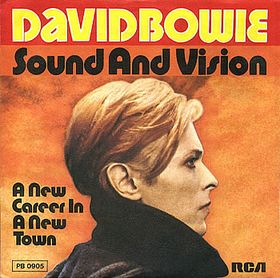

David Bowie, "Sound and Vision" (1977)

(listen)

Who says you can't learn anything by reading Wikipedia? I just found out not only that producer Tony Visconti was married to Mary Hopkin (who had a #2 hit late in 1968 with "Those Were the Days") but also that she's among the backing vocalists on this very early fruit of the collaboration between David Bowie and Brian Eno. Released as the first single from their first album working together, Low, "Sound and Vision" did pretty well in Europe but fizzled in the States, never even cracking the top 40. A pity, and all the more reason I was utterly thrilled in 1978 to find it parked on a jukebox at a greasy burger joint in a strip mall in St. Louis Park, Minnesota, near where I was living at the time. I actually dragged pals to that dump so we could sit there and play it over chocolate shakes—it was the public declaration of fealty to strange snaky sounds that had already won me over and somehow come to mean so much. The big whomping attack and the stately tempo it sets before it starts layering itself up and down with the lovely coruscating sheets and bolts of soundscape. It says here Bowie slashed away at the already minimal lyrics to leave space for the song to breathe. Well, there's so much space here it practically gasps and it's all shoved right up front; not even the background vocals come in for 45 seconds, and it's not until the 1:28 mark that Bowie on the lead vocal finally appears. Already Bowie and Eno were showing new ways around a three-minute pop songs—it's practically the first thing they did. Oh, and P.S. in case you were wondering the 1977 original is way better than the buffed-up 1991 remix.

Who says you can't learn anything by reading Wikipedia? I just found out not only that producer Tony Visconti was married to Mary Hopkin (who had a #2 hit late in 1968 with "Those Were the Days") but also that she's among the backing vocalists on this very early fruit of the collaboration between David Bowie and Brian Eno. Released as the first single from their first album working together, Low, "Sound and Vision" did pretty well in Europe but fizzled in the States, never even cracking the top 40. A pity, and all the more reason I was utterly thrilled in 1978 to find it parked on a jukebox at a greasy burger joint in a strip mall in St. Louis Park, Minnesota, near where I was living at the time. I actually dragged pals to that dump so we could sit there and play it over chocolate shakes—it was the public declaration of fealty to strange snaky sounds that had already won me over and somehow come to mean so much. The big whomping attack and the stately tempo it sets before it starts layering itself up and down with the lovely coruscating sheets and bolts of soundscape. It says here Bowie slashed away at the already minimal lyrics to leave space for the song to breathe. Well, there's so much space here it practically gasps and it's all shoved right up front; not even the background vocals come in for 45 seconds, and it's not until the 1:28 mark that Bowie on the lead vocal finally appears. Already Bowie and Eno were showing new ways around a three-minute pop songs—it's practically the first thing they did. Oh, and P.S. in case you were wondering the 1977 original is way better than the buffed-up 1991 remix.

Tuesday, March 06, 2012

Videodrome (1983)

#45: Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983)

I like what David Thomson, writing in the 2002 edition of his New Biographical Dictionary of Film, has to say about David Cronenberg: "Anyone born and reckoning on dying needs to confront Cronenberg."

I knew I wanted to get at least one of my three favorites by him in here, all from the '80s—Dead Ringers, The Fly, or Videodrome. Even though it's going to take us six months to get through them, 50 actually ends up being kind of a short list, and sometimes you just have to pick one from among many.

I like what David Thomson, writing in the 2002 edition of his New Biographical Dictionary of Film, has to say about David Cronenberg: "Anyone born and reckoning on dying needs to confront Cronenberg."

I knew I wanted to get at least one of my three favorites by him in here, all from the '80s—Dead Ringers, The Fly, or Videodrome. Even though it's going to take us six months to get through them, 50 actually ends up being kind of a short list, and sometimes you just have to pick one from among many.

Sunday, March 04, 2012

Best American Crime Writing 2003

The second volume of the late lamented annual series of true-crime writing is heavily shadowed by 9/11—inevitably two of the pieces here include the word "terrorist" in their titles and at least as many more concern themselves with various crimes of foreign policy. That's interesting too, certainly in the pieces found here, as are other topical pieces, such as Marie Brenner's longish "The Enron Wars," originally from "Vanity Fair." John Berendt, author of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, provides the introduction (no editing input, evidently), using the platform to criticize some of the excesses of the so-called USA Patriot and Homeland Security legislation, a welcome view then and something of a brave one too. So hear-hear, huzzah, and bravo to him. Nevertheless, the pieces I tend to like best as usual are more concerned with the mundane eccentricities and perversions of everyday life. For example, "The Day Treva Throneberry Disappeared" by Skip Hollandsworth (a very good writer who appears in this series frequently), which is about a woman in her 30s who has spent much of her adult life impersonating high schoolers. "The Bully of Toulon" by Robert Kurson charts the tragic ending of decades of simmering tensions in a small Midwestern town. "My Undertaker, My Pimp" by Jay Kirk from "Harper's" details unexpected corruption in an unusual place; Kirk never particularly seems to feel he is writing about crime, a surprisingly fresh point of view in the context. My favorite in this volume is a straightforward piece of documentary journalism, profiling an ongoing development in forensic science. "The Body Farm" by Maximillian Potter (from "GQ"!) is about "a two-acre patch of Tennessee woods that is surrounded by an eight-foot-high fence topped with razor wire." Here, bodies that have been donated to the scientific cause are strewn about with deceptive casualness—partly buried, buried in shallow graves, lying on the ground, sitting up against tree trunks, tied to trees. They have been left to decompose and researchers are there to chart it with care. Determining time of death is often critical for homicide investigators and these ongoing experiments contribute to that knowledge, and so here we are, with these sudden fever visions of a carnival hellhouse scenario, rotting corpses scattering the woods willy-nilly and the woods taking back its own. This has also been covered on true-crime TV now, but the most vivid descriptions of it, which haunt me still, are in the Potter piece here. And, as usual, everything else here is pretty good too.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, March 03, 2012

Hearts and Bones (1983)

Listening to these old Paul Simon albums lately, this is the one that has somehow ended up sounding best. I always liked it, even back then, when it was taken as more or less too-bad-so-sad aimless drifting. And there's a case to be made for that. But all the conceits Simon reaches for here—the Diaspora, French surrealism and some of the most beautiful music of the '50s, modes of modern conveyance, and even numerals, all in the context of gittin' the durn songs written, the songwriter as gentle (and gently affected) working man—actually feel organic and credible to me on close examination. Or organic and credible enough. Simon found a way to be natural here—rueful, light-hearted, and earnest, all by turns, all seductive and all believable. I mean, I know, forget it, Jake, it's Paul Simon. A life of means and imposing sense of bruised presence is the given; it's where we have to start. But I don't know how many other places he puts his natural songwriting skills to work in such a relaxed, freewheeling go. He's positively playful on goofs such as "When Numbers Are Serious," "Song About the Moon," or "Cars Are Cars." "Rene and Georgette Magritte With Their Dog After the War" dares to go where the titles are obnoxiously long and wordy and pretentious and comes back with something exceedingly lovely, swirling round itself like the gauzy fabrics wielded by Stevie Nicks on stage the names and hints and faint echoes of the sounds of such lovingly recalled vocal group acts of the '50s as "the Penguins, the Moonglows, the Orioles, and the Five Satins." It continues to work even as he sings in French, largely, again, because I think that's some of the music Simon was most personally affected by. It's coming from an authentic place. Then there is a "Think Too Much" suite, with the "B" version preceding the "A" by two tracks (and I believe opposing sides of the vinyl LP), which of course is slyly designed to produce the effect described in their titles, and presumably the songs too, though as always I often find my attention wandering when I start trying to pay close attention to Paul Simon's actual streams of words. The homerun for me here is the closing track, "The Late Great Johnny Ace," which conflates the deaths of Johnny Ace in 1954 and John Lennon in 1980, with their curious rhyming points, and soars on its own bittersweet fragments of recollections, which constantly threaten to become suffocating but never quite tip over (YMMV). The song, the side, the album ends on a beautiful, confounding, and haunting minute composed by Philip Glass for strings, clarinet, and flute, effectively a kind of "A Day in the Life"/"Eleanor Rigby" memoriam by its perfectly canny placement.

Friday, March 02, 2012

Persona (1966)

Sweden, 85 minutes

Director/writer: Ingmar Bergman

Photography: Sven Nykvist

Music: Lars Johan Werle

Editor: Ulla Ryghe

Cast: Bibi Andersson, Liv Ullmann, Margaretha Krook

From its earliest images to its tidy, perfunctory ending, a span of a mere 85 minutes, Persona is determinedly difficult and modern, dense and stark. The music by Lars Johan Werle is harsh and discordant. Director and writer Ingmar Bergman borrows from the immediacy of the documentary newsreel with footage of a self-immolating Buddhist monk in Vietnam. There is an erect penis, medical photography, a live dissection, religious symbology. There are images that go by so fast we can't be sure what they are. There is footage of earliest cinema and crude animation. There are white screens and black screens.

Bergman even almost taunts us at points, I think, daring us for example to question his audaciously unbelievable premise: a famous actress of stage and screen endures an existential crisis and stops speaking. That's it. It's as patently silly in its way as the image of Jean-Paul Belmondo running across a field in his ridiculous suit after he has killed a policeman in Breathless.

Yet the minute it starts, every time, I find it impossible to take my eyes off Persona.

Director/writer: Ingmar Bergman

Photography: Sven Nykvist

Music: Lars Johan Werle

Editor: Ulla Ryghe

Cast: Bibi Andersson, Liv Ullmann, Margaretha Krook

From its earliest images to its tidy, perfunctory ending, a span of a mere 85 minutes, Persona is determinedly difficult and modern, dense and stark. The music by Lars Johan Werle is harsh and discordant. Director and writer Ingmar Bergman borrows from the immediacy of the documentary newsreel with footage of a self-immolating Buddhist monk in Vietnam. There is an erect penis, medical photography, a live dissection, religious symbology. There are images that go by so fast we can't be sure what they are. There is footage of earliest cinema and crude animation. There are white screens and black screens.

Bergman even almost taunts us at points, I think, daring us for example to question his audaciously unbelievable premise: a famous actress of stage and screen endures an existential crisis and stops speaking. That's it. It's as patently silly in its way as the image of Jean-Paul Belmondo running across a field in his ridiculous suit after he has killed a policeman in Breathless.

Yet the minute it starts, every time, I find it impossible to take my eyes off Persona.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)