(listen)

Honestly I never figured out until I saw it the other day in Wikipedia that the anagram of the title is "Talking Heads." Gratification. Relief. At long last. Why didn't anybody ever tell me?! Robert Christgau's review of Before and After Science alluded to it, and I don't know why I didn't get it. I'm usually pretty good at anagrams. I guess I got stuck on "death"—I thought it had to include "death." But no, just some greeting from afar to a musical relationship that was about to take off like rockets. "King's Lead Hat" was always my favorite song on the album. Much like "Third Uncle" on Taking Tiger Mountain, my other favorite album by Eno, it's about as hard as Eno was ever going to rock, in the context of albums that were themselves as rocking as he was ever going to get ... more or less. But he really pours everything into this, with a wall of sound affect that swarms like all 17 musicians listed on the credits could have chipped in. It fades up quickly to full-scorch groove and continues from there, with Eno yelping along with a nursery rhyme kinda melody on top of the stone groove, and it breaks wide open at the chorus, goes a little robo-loopy at the bridge, pirouettes and drops to a knee. It's fun, it's ecstatic, and there's a feeling of discovery about it. I see that it was released as the only single from the album and never did anything, even in the UK. So I will have to acknowledge that in many ways Eno's entire '70s catalog (heck, the whole career) is on the order of a cult level of operations. I want to sign up to be a priest in this cult.

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

Brian Eno, "King's Lead Hat" (1977)

Sunday, February 24, 2013

Fear of Falling: The Inner Life of the Middle Class (1989)

Barbara Ehrenreich's late-'80s meditations on the foibles of the American middle class from the '50s to the '80s is arguably badly dated now. In many ways it put me in a foul, depressed mood simply because so many of the worst trends she identified have only worsened, metastasized, in the 20+ years since it was published: irrational public policies toward poverty, work, money, family, and moral values, along with the ongoing debasement by right-wing politics. It's all here. Even income inequality, which she makes a good case was getting pretty bad in the late '80s, has only worsened by orders of magnitude. It's apparent that the American wealthy have been playing a very shrewd long game, and that they are still. It is so bad that it is tempting to say simply that they have won, that they have won and the rest of us can all go home now and accept our crumbs. But the Charlie Brown in me sees perpetual shoots and leaves in things such as last fall's election cycle, which in spite of everything was tremendously satisfying, however momentary. Back in 1989, Ehrenreich was getting into Nixon's politics of resentment. She doesn't call it that, but it's the familiar idea of siphoning away the blue-collar working class from the professional middle class and pitting the two groups against one another on culture-values issues such as welfare and feminism. The pendulum will swing back again, I'm convinced of that (provided we can survive as a species)—the pendulum always swings back. But the difference between now and the last time we were in such unbalanced circumstances, during the Great Depression of the 1930s, is that now we don't necessarily have the equivalents of fascists on the right and communists on the left to force cooperation from the wealthy. Sadly enough, it looks to me like we will now have to go all the way through all those gyrations again. And I'm probably too old now to witness it anyway. So the high point in my lifetime in terms of public policy is likely to remain approximately 1972. A book like this, which so carefully and artfully (and outdatedly) dissects how we approached that point and sailed through it and went on to ignore all the historical lessons that led up to it ... well, it's useful enough one way or another, I suppose. But it's also extremely painful. </craven self-pity>

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, February 23, 2013

Heathen (2002)

Along the David Bowie comeback trail I must admit that this is (another) one I missed. Full disclosure: I have been off the David Bowie comeback trail since Let's Dance and certainly by Tin Machine. But to be perfectly clear, I bear him no real ill will. I just lost interest. Not even Outside, the 1995 reunion with Brian Eno, ever had much appeal. Some of the albums I arrived at late, perhaps most notably 1984's Tonight, possibly 1987's Never Let Me Down, turned out to be better than expected. But I have learned to be cautious with this fine old fellow. A little study clarifies the appeal of Heathen—mostly the familiar Thin White Duke/Bing Crosby persona reunited with a bunch of the old gang. A good bet. Tony Visconti, last seen with Bowie on Scary Monsters, is the producer, and those on hand include something new and something old at every turn: Carlos Alomar, Lisa Germano, Dave Grohl, Tony Levin, Pete Townshend, etc. There are covers of songs by the Pixies, Neil Young, and the Legendary Stardust Cowboy (which when listed that way appear almost focus-grouped in their clinical precision), but most of the songs are by Bowie. Now I would be kidding you if I tried to say this didn't have its share of some very delectable moments, e.g., the surprising crispness of Townshend's texturing on "Slow Burn," the sultry and effective mood of "I Would Be Your Slave," a certain vaguely retro charm to "I Took a Trip on a Gemini Spaceship," with some nice horns too, and especially the callow beauties of "Everyone Says 'Hi'," which somehow for me connects all the way back to the earliest songs he wrote, when it was Davy Jones & the Lower Third. And the sound of Heathen is resolutely familiar and comforting. There's no doubt about that—I never mind hearing it play. But ultimately it just kind of sits there and flops around a little. I note the nice moments in passing. The rest of it fades hard into the background. Even when I try to concentrate on it my mind wanders. It's just the same old problem. It doesn't interest me that much. I like it more than Outside, but maybe not as much as Tonight. Let me put it that way.

Friday, February 22, 2013

Traffic (2000)

Germany/USA, 147 minutes

Director/photography: Steven Soderbergh

Writers: Simon Moore, Stephen Gaghan

Music: Cliff Martinez

Editor: Stephen Mirrione

Cast: Michael Douglas, Benicio Del Toro, Don Cheadle, Luiz Guzman, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Dennis Quaid, Erika Christensen, Topher Grace, Amy Irving, Albert Finney, Clifton Collins Jr., Tomas Milian, James Brolin, Steven Bauer, Miguel Ferrer, D.W. Moffett, Peter Riegert, Harry Reid, Orrin Hatch, Viola Davis, John Slattery

However permanent it may or may not turn out to be, Steven Soderbergh's scheduled exile from filmmaking has motivated me to pile on his surprisingly big output as a director (and editor, and cinematographer) and do some catching up. He has had his prolific periods. Traffic, which I saw when it was new, was a part of a rush of work he released at the turn of the century, with The Limey (still my one favorite by him, despite its unfortunate influence), Erin Brockovich, and Ocean's Eleven, all released within a year or two of one another.

Traffic may be the most self-consciously "serious" of them, pretty close when all is said and done to what used to be called a "message picture." The societal issue under discussion is public policy on recreational drugs, and the message is "the War on Drugs is not working." It helps that I am heartened to see the issue taken on and that message delivered, but it helps even more that the movie, though not without flaws, is also a pleasure to watch, a great big snack cake of a movie, with a relaxed confidence about knowing what it is and what it can and cannot do, packed full of memorable performances, and deftly managing the subtleties and nuances not just of the characters and their interactions, but perhaps more importantly (for me, in this instance) of the sensitive, complex, and explosive issue at its core.

Director/photography: Steven Soderbergh

Writers: Simon Moore, Stephen Gaghan

Music: Cliff Martinez

Editor: Stephen Mirrione

Cast: Michael Douglas, Benicio Del Toro, Don Cheadle, Luiz Guzman, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Dennis Quaid, Erika Christensen, Topher Grace, Amy Irving, Albert Finney, Clifton Collins Jr., Tomas Milian, James Brolin, Steven Bauer, Miguel Ferrer, D.W. Moffett, Peter Riegert, Harry Reid, Orrin Hatch, Viola Davis, John Slattery

However permanent it may or may not turn out to be, Steven Soderbergh's scheduled exile from filmmaking has motivated me to pile on his surprisingly big output as a director (and editor, and cinematographer) and do some catching up. He has had his prolific periods. Traffic, which I saw when it was new, was a part of a rush of work he released at the turn of the century, with The Limey (still my one favorite by him, despite its unfortunate influence), Erin Brockovich, and Ocean's Eleven, all released within a year or two of one another.

Traffic may be the most self-consciously "serious" of them, pretty close when all is said and done to what used to be called a "message picture." The societal issue under discussion is public policy on recreational drugs, and the message is "the War on Drugs is not working." It helps that I am heartened to see the issue taken on and that message delivered, but it helps even more that the movie, though not without flaws, is also a pleasure to watch, a great big snack cake of a movie, with a relaxed confidence about knowing what it is and what it can and cannot do, packed full of memorable performances, and deftly managing the subtleties and nuances not just of the characters and their interactions, but perhaps more importantly (for me, in this instance) of the sensitive, complex, and explosive issue at its core.

Thursday, February 21, 2013

D

Perhaps because it is reputed that stupid people are prone to saying, "Duh," but more likely because of the letter grade, the letter D comes with a deceptive reputation as an underachiever. (Note also Tweedledum and Tweedledee.) The letter grade, in fact, deserves a moment all to itself. Think about this: a D. "I got a D." What does this mean? It is a particularly cruel way of failing without technically failing, more on the order of a humiliation, incidentally saying more about the system that designed the grade (duh). But it's also due to the way the letter D stands for things like down, don't, dirty, disgusting, depraved, denigrated, deranged, and degenerate. Well, somebody has to! It appears to be a self-esteem problem of some kind, always tending back again toward that familiar semblance of underachievement. Look, for example, at how it insinuates itself into the word "mediocre," virtually enlisting one to allocute one's own failings Bizarro style simply by pronouncing it. Can you hear what the letter D and its dumb baggage is making you say? "Me D." That's what you're really saying. "It was mediocre. Mediocre. Me D." Hey, me feel same way, Bizarro. Me am also D. (Also applies with even more ominous implications to "medieval.") This raises a question. What were the Greek alphabet makers thinking when they put D fourth in line? Is it something about the mouth noise, voiced brother to the plosive T? And if so, what? As we have seen already with A, B, and C, it isn't frequency of use that's winning this contest. The letter D ranks only #10 on that scale. And doesn't that also, in the end, actually make the letter D an overachiever? You see where I am going. Well, it does make a bit of a silly, pot-bellied figure, doesn't it? All military posture on the left and then the flab on the right (or vice versa, approximately, face right, with the lowercase d). The letter D also belongs to the large family of letters that rhyme with E, their spiritual progenitor as it were: B, C, D, E, G, P, T, V, and Z. Represent! (I understand those with stronger ties to the British mother tongue are wont to say "zed" for Z, but that is a topic for another time, duh.) Another question: Does anyone like the letter D? Why? It seems unassuming to the point of bland neglect, indubitably inscrutable. Yet somehow paradoxically it always manages to overachieve again. Consider: The strongest fingers on our hands are, as everybody knows (after the thumbs, duh), the middle fingers. And look who's sitting there under your left-hand middle finger with pride of place, waiting to take the punishment. None other than ... well, duh. Man, sometimes I think the letter D just sits there and waits to get everything handed to it on a platter. It's the spoiled, practically worthless brat of the alphabet. Why, I oughtta. But wait a second now. It's also an honest letter, doing an honest day's work, with a single unique sound that no other letter uses. What's more, it's widely common among many, many languages, if not all of them. Somebody stop me from actually typing, "So cred

Wednesday, February 20, 2013

David Bowie, "Moonage Daydream" (1972)

Here's a nice David Bowie song from the Ziggy Stardust album. I have never entirely made up my mind whether I believe it's an album that should be listened to entire, front to back the way intended, in respect of its thematic aspirations (not to say pretensions). But shuffle has obviated all such questions anyway. "Moonage Daydream" plays big with the central concept about the alien who becomes a rock star or something. "Point your ray gun to my head," it goes at one point, "press your space face close to mine," etc. A wheetling baroque bridge comes in at the break. Some real nice guitar play. It's got the starchy Bowie sumptuousness, that crinkly dandy in tails with the operatic sense of doominess he has always managed so convincingly. He sometimes maybe means to be something rather more (and "other") than a dandy, but back of it all, always, is ... a dandy. He knew it, we knew it, he knew we knew it, and most of us were pretty sure he knew we knew it. "Don't fake it baby, lay the real thing on me / The church of man, love / Is such a holy place to be." That's what he's singing, man. That's part of what made it work so well for so long, and still can. But as for this, my quandary about the album is revived when I look at the list of songs: "Five Years," "Starman," "Star," "Ziggy Stardust" (one begins to detect a theme), and of course "Suffragette City" and "Rock 'n' Roll Suicide." Just tremendous, iconic stuff, and still sounds so good with Mick Ronson and the stuffy noise they concocted and the whole story and fashion passion drama too. Just wonderful kooky stuff. And, at that, "Moonage Daydream" belongs. It's also kooky and wonderful.

Tuesday, February 19, 2013

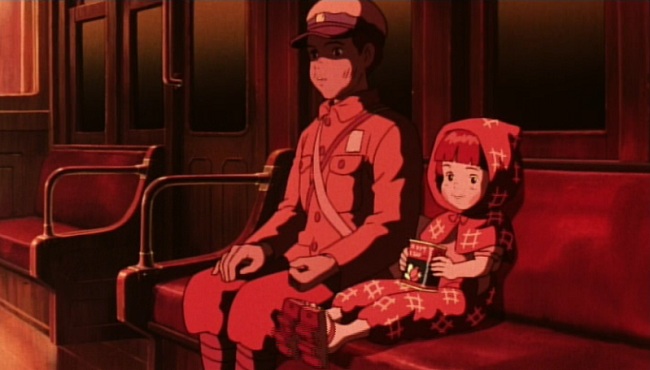

Grave of the Fireflies (1988)

Hotaru no haka, Japan, 89 minutes

Director: Isao Takahata

Writers: Akiyuki Nosaka, Isao Takahata

Production design: Ryoichi Sato

Art direction: Nizou Yamamoto

Music: Michio Mamiya

Editor: Takeshi Seyama

Cast/voices (English version): Rhoda Chrosite, J. Robert Spencer, Amy Jones, Veronica Taylor

Currently ranked at #110 on the user-voted list of the IMDb Top 250, with an average rating of 8.3/10 as of this writing, I suspect Grave of the Fireflies needs little introduction. Conceived originally as the historical/educational half of a double feature and paired with another early and popular effort from Studio Ghibli, My Neighbor Totoro—yes, the two could only be seen in the company of one another in their original release—Grave of the Fireflies has since gone on to occupy its unique position in cinema and animation history as one of the saddest and most powerful features of its kind. Nothing comes close unless you start to consider live-action pictures and even there it stacks up pretty well.

I like it too. The temptation always is simply to erupt with superlatives, but in terms of its cultural impact I'm not sure it can be overstated. Without Grave of the Fireflies you don't get the incinerator scene in Toy Story 3, for one example (or, also from Pixar, the first 10 minutes of Up). The closest analogue might be Art Spiegelman's Maus, which similarly took a vastly underestimated medium (comic books, as opposed to cartoon features) and made practically unprecedented strides in legitimizing it once and for all. Interestingly, they both accomplished this feat by grounding their stories in that great legitimizer of the 20th century, World War II.

Director: Isao Takahata

Writers: Akiyuki Nosaka, Isao Takahata

Production design: Ryoichi Sato

Art direction: Nizou Yamamoto

Music: Michio Mamiya

Editor: Takeshi Seyama

Cast/voices (English version): Rhoda Chrosite, J. Robert Spencer, Amy Jones, Veronica Taylor

Currently ranked at #110 on the user-voted list of the IMDb Top 250, with an average rating of 8.3/10 as of this writing, I suspect Grave of the Fireflies needs little introduction. Conceived originally as the historical/educational half of a double feature and paired with another early and popular effort from Studio Ghibli, My Neighbor Totoro—yes, the two could only be seen in the company of one another in their original release—Grave of the Fireflies has since gone on to occupy its unique position in cinema and animation history as one of the saddest and most powerful features of its kind. Nothing comes close unless you start to consider live-action pictures and even there it stacks up pretty well.

I like it too. The temptation always is simply to erupt with superlatives, but in terms of its cultural impact I'm not sure it can be overstated. Without Grave of the Fireflies you don't get the incinerator scene in Toy Story 3, for one example (or, also from Pixar, the first 10 minutes of Up). The closest analogue might be Art Spiegelman's Maus, which similarly took a vastly underestimated medium (comic books, as opposed to cartoon features) and made practically unprecedented strides in legitimizing it once and for all. Interestingly, they both accomplished this feat by grounding their stories in that great legitimizer of the 20th century, World War II.

Monday, February 18, 2013

Tempest (2012)

I was talking just the other day about the tempestuous relationship so many of his fans have had with Bob Dylan. I followed a fairly familiar path, connecting with most of his best '60s albums slightly after the fact, as a teen in high school in the early '70s, then losing him across the course of the '70s until the Jesus period, when I checked out completely until Oh Mercy, coming back all the way with Time Out of Mind. He's just one of my favorites now, there I said it, it's a cliché, I accept that. He is willfully obtuse, a scoundrel and rascal, can't sing very well (and now his voice is shot), can't play guitar either, isn't a nice guy, and yeah, probably laughing at me. I don't know what the songs mean, or in this context, even exactly what the meaning of songs means. He's not exactly comfortable, I know that, and often annoying as hell. But almost always interesting, in a way that is notably difficult to describe. More on this later. In the new century, "Love and Theft" set the terms of the current state of the crisscrossing blues rock 'n' roll roots forms with rambling talk songs, well and truly introducing the expedient of absolutely first-rate bands producing unpretentiously amazing grooves. It was best on that album, from 2001, a little bit off on Modern Times, from 2006, and now a little bit further off here. He seems content to work out batches of songs like this every few years and I'm content to enjoy them for a few weeks. The song lengths here start at three and a half minutes and range on up to nearly 14 minutes for the title song, which, it must be said, doesn't deserve such breadth, but at least is unassuming about it. My favorites tend to take it up a little notch—thinking of "Narrow Way," for example (7:28), or "Early Roman Kings" (5:14), maybe the best thing here. Yes, "Roll On John" is extremely unfortunate. More broadly the tell, as always, is the humor, and the fact is that the jokes mostly aren't that funny on Tempest. But all right. Larger truth still in place. He has aged well. It is more and more looking like a life well lived, which seemed impossible at multiple points since 1962. Somehow the stakes still seem to matter, although there's a good chance that's just me.

Sunday, February 17, 2013

The House on the Strand (1969)

Now and then I think I might want to make a project of Daphne du Maurier, as much as anything because she wrote the original literary properties for a few Alfred Hitchcock movies, including Rebecca and The Birds. The House on the Strand, which is out of print as far as I can tell (and whatever that means exactly nowadays ... I found it online as a penny hardback), comes with an unusual twist on science fiction time travel, which I suppose is how I happened to get to it first. The twist is that time travel happens because of taking a drug, and essentially it's only the consciousness that actually travels as the physical body stays put in the present in something of a trance-like state, although it moves as the time traveler moves across the landscape of the past (and woe to you if something has been built there in the meanwhile). The theoretical basis is a lot of nonsensical argle-bargle, but never mind—that's as much feature as bug to me in the time travel subgenre, which I adore for itself. Unfortunately, in this novel, the 14th-century story that so fascinates our protagonist bore little interest for me, overpacked with tedious details of the long-ago characters and their byzantine interrelations and intrigues. What I found more interesting was the nature of the drug use itself, which du Maurier facilely compares to LSD (no coincidence that the book was published in 1969, near the zenith of the drug's renown), terming the experiences "trips" and larding them out with various hallucinatory details. I wouldn't be surprised if du Maurier had done some experimenting of her own, though she was really most convincing to me on the patterns of addiction itself, never that much of a problem with the hallucinogen class, as far as I know. But in terms of the secretive way of living, the double life, compulsions, and the insanity of continuing to use in the face of undeniable dangers, her novel seems to me strikingly on the mark, and the most interesting aspect of it by far. It closes on something of a cheesy note, but there are moments here when one groans in empathetic horror at the choices and actions of our hero, which means it's not entirely without merit. Even so, overall, that's kind of a thin reed from which to hang things that are all too often boring, inconsequential, and way too outdatedly trendy. Proceed with caution.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, February 16, 2013

Wave (1979)

Maybe I'm kind of an oddball Patti Smith fan, because after Horses, which safely qualifies as life-changing, this almost sad gesture toward the mainstream is my favorite album by her. Todd Rundgren as producer used to strike me as strange—in 1975, when I most adored both of them, separately, it never occurred to me their paths could cross. I recall Patti Smith in 1979 widely considered as something of a problem—unfocused, hysterical, an embarrassment. Going off a high stage in 1977 and breaking her neck was part of it. Being a woman was probably more of it. Ultimately it didn't matter because she married and went away soon after this, and five years later the whole episode felt a bit like a dream. But I really warmed to Wave once it found its way into my house, as a cutout a year or two later, if memory serves. It starts strong with the three singles, "Frederick," "Dancing Barefoot," now practically a signature song, and a cover of "So You Want to Be (A Rock 'n' Roll Star)," which reminded us, if we needed the reminder, and I think we did, that the majority of her most ecstatic roots were playing on the radio between 1964 and 1967. The focus is mostly lost by the back side of the set but momentum carries it; that and a natural focus on those first three songs, which drew me back continually. When I was working this into the shuffle in anticipation of writing about it I was at first alarmed by how weak these random songs were. But once I played it in track sequence from start to finish it all came back. As for the professional polish, yeah, it's there. But I don't think the intentions were on the order of selling out. I think they have more to do with a needy artist who needs love and has always been perfectly willing to put that out there. She does her thing, and always has, but there's one eye cocked on the audience at all times. There's no other way she could have possibly become one of the great rock 'n' roll performers, which is what she was at least the night I saw her in 1976. She was trying to please then and she's trying to please here. And not making a bad job of it either.

Friday, February 15, 2013

Stop Making Sense (1984)

USA, 88 minutes, documentary

Director: Jonathan Demme

Writers: Jonathan Demme, Talking Heads

Photography: Jordan Cronenweth

Music: Talking Heads: David Byrne, Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz, Jerry Harrison, Ednah Holt, Lynn Mabry, Steven Scales, Alex Weir, Bernie Worrell

Editor: Lisa Day

It's interesting to think about what one does with favorite bands. As a point of conversation I used to argue for the importance of always having one, or several: favorite locals, favorite performers, favorite within genres, favorite favorites. At some points, overwhelmed by so many choices, it becomes a pretty good problem to have. Many happy years can go by where the thought is basically on when a next album is coming out and/or a next show happening. Then one day something changes—the band breaks up, puts out a bad album, somebody says something stupid, a death—something—and it doesn't have the same allure anymore.

Talking Heads were like that for me, my favorite band from 1978 when I first heard the debut and then the follow-up. I stuck with them all the way to 1986 and True Stories, which was too rancid, and left a bad taste that's still there. Stop Making Sense was a high point of the good years, coming even as the band was visibly beginning to fracture and it was easy to wonder each time if there was going to be anything more. I saw the movie on its release and it was more than I could have hoped for, as was the album that followed the next year, Little Creatures, the last good thing they ever did. I actually saw Stop Making Sense a few times, and that was back when it felt more like an odd extravagance to see a movie more than once. Then it became a casualty of backlashing reassessments.

Director: Jonathan Demme

Writers: Jonathan Demme, Talking Heads

Photography: Jordan Cronenweth

Music: Talking Heads: David Byrne, Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz, Jerry Harrison, Ednah Holt, Lynn Mabry, Steven Scales, Alex Weir, Bernie Worrell

Editor: Lisa Day

It's interesting to think about what one does with favorite bands. As a point of conversation I used to argue for the importance of always having one, or several: favorite locals, favorite performers, favorite within genres, favorite favorites. At some points, overwhelmed by so many choices, it becomes a pretty good problem to have. Many happy years can go by where the thought is basically on when a next album is coming out and/or a next show happening. Then one day something changes—the band breaks up, puts out a bad album, somebody says something stupid, a death—something—and it doesn't have the same allure anymore.

Talking Heads were like that for me, my favorite band from 1978 when I first heard the debut and then the follow-up. I stuck with them all the way to 1986 and True Stories, which was too rancid, and left a bad taste that's still there. Stop Making Sense was a high point of the good years, coming even as the band was visibly beginning to fracture and it was easy to wonder each time if there was going to be anything more. I saw the movie on its release and it was more than I could have hoped for, as was the album that followed the next year, Little Creatures, the last good thing they ever did. I actually saw Stop Making Sense a few times, and that was back when it felt more like an odd extravagance to see a movie more than once. Then it became a casualty of backlashing reassessments.

Labels:

1984,

Demme,

docs,

movie of the year,

Talking Heads

Wednesday, February 13, 2013

English Beat, "Twist & Crawl" (1980)

(listen)

From the (English) Beat's amazing debut, I Just Can't Stop It, which is essential. This song was never a hit or even a single as far as I know but it got to be my favorite, probably because it was about the point where I could feel my neck starting to snap off from the rapid-fire assault of tempo on that first vinyl side, and I was impelled to get up and in for some living room dance time. It followed "Mirror in the Bathroom," which kicked the side off splendidly, and two more good ones, culminating ultimately with "Click Click," at 1:28. "Twist & Crawl" at 2:34 is more of your everyday type of impossibly fast quick-stepper. Once started, if you try to keep time to it nodding your head, you will see what I am talking about. Oh, sweet youth. The band at this moment at the top of their powers, something to behold, even just hearing them on the album. The simple unassuming way it enters in, built from drum patterns, then bass and rhythm guitar, insinuating itself even as it subtly boosts the tempo, playing it faster and faster, but not so you notice much until the painful neck snapping interrupts your reverie. Time to get on your feet now. Alas, from here the English Beat just went to fracturing, though not without its pleasures along the way. Over the long decades it has evolved into one unit called the Beat (UK), headed up by Ranking Roger, and another called the English Beat (US), fronted by Dave Wakeling. A friend reports in from a recent English Beat (US) show in Annapolis that Dave Wakeling was embarrassingly drunk, but Antonee First Class kept it together and made it work—good show, overall.

From the (English) Beat's amazing debut, I Just Can't Stop It, which is essential. This song was never a hit or even a single as far as I know but it got to be my favorite, probably because it was about the point where I could feel my neck starting to snap off from the rapid-fire assault of tempo on that first vinyl side, and I was impelled to get up and in for some living room dance time. It followed "Mirror in the Bathroom," which kicked the side off splendidly, and two more good ones, culminating ultimately with "Click Click," at 1:28. "Twist & Crawl" at 2:34 is more of your everyday type of impossibly fast quick-stepper. Once started, if you try to keep time to it nodding your head, you will see what I am talking about. Oh, sweet youth. The band at this moment at the top of their powers, something to behold, even just hearing them on the album. The simple unassuming way it enters in, built from drum patterns, then bass and rhythm guitar, insinuating itself even as it subtly boosts the tempo, playing it faster and faster, but not so you notice much until the painful neck snapping interrupts your reverie. Time to get on your feet now. Alas, from here the English Beat just went to fracturing, though not without its pleasures along the way. Over the long decades it has evolved into one unit called the Beat (UK), headed up by Ranking Roger, and another called the English Beat (US), fronted by Dave Wakeling. A friend reports in from a recent English Beat (US) show in Annapolis that Dave Wakeling was embarrassingly drunk, but Antonee First Class kept it together and made it work—good show, overall.

Tuesday, February 12, 2013

The Little Mermaid (1989)

USA, 83 minutes

Directors: Ron Clements, John Musker

Writers: John Musker, Ron Clements, Hans Christian Andersen, Howard Ashman, Gerrit Graham, Sam Graham, Chris Hubbell

Art direction: Michael Peraza Jr., Donald Towns

Music: Alan Menken

Editor: Mark A. Hester

Cast/voices of: Jodi Benson, Pat Carroll, Samuel E. Wright, Buddy Hackett, Rene Auberjonois, Christopher Daniel Barnes, Paddi Edwards, Jason Marin, Kenneth Mars, Edie McClurg, Will Ryan, Ben Wright

The Little Mermaid is likely best known today as the picture that launched the Disney Renaissance, marking a return to form for the studio of a certain level of charm and brio. Following the deaths of co-founders Walt and Roy Disney in the '60s and '70s, the company had spent years wandering the deserts of mediocrity. After The Little Mermaid would come Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King, and many others through the '90s, most of them massive moneymakers. It may be tempting to locate the start of any such renaissance back one year, to the studio's collaboration with Steven Spielberg in 1988 on Who Framed Roger Rabbit. In many ways, that's the picture that restored interest among mainstream audiences in feature-length animated entertainment (or semi-animated, as it mixes live action with the cartoons). But Roger Rabbit, for all its many impressive virtues, is hardly in the Disney style.

That would be the job of The Little Mermaid. No doubt there are volumes of behind-the-scenes corporate backstory to this movie, involving industry players, gutsy business calls, and various career-making and -breaking maneuvers. It's also easy enough to pick out various elements and call "formula"—yet another princess story based on yet another Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, yet another musical, and, as always, damnably cute more than 70% of the time. But in the end that's incidental to what ended up on the screen. In the watching, The Little Mermaid is one of those happy accidents where all pieces fall together and the result is something close to an ideal, achieved seemingly effortlessly.

Directors: Ron Clements, John Musker

Writers: John Musker, Ron Clements, Hans Christian Andersen, Howard Ashman, Gerrit Graham, Sam Graham, Chris Hubbell

Art direction: Michael Peraza Jr., Donald Towns

Music: Alan Menken

Editor: Mark A. Hester

Cast/voices of: Jodi Benson, Pat Carroll, Samuel E. Wright, Buddy Hackett, Rene Auberjonois, Christopher Daniel Barnes, Paddi Edwards, Jason Marin, Kenneth Mars, Edie McClurg, Will Ryan, Ben Wright

The Little Mermaid is likely best known today as the picture that launched the Disney Renaissance, marking a return to form for the studio of a certain level of charm and brio. Following the deaths of co-founders Walt and Roy Disney in the '60s and '70s, the company had spent years wandering the deserts of mediocrity. After The Little Mermaid would come Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, The Lion King, and many others through the '90s, most of them massive moneymakers. It may be tempting to locate the start of any such renaissance back one year, to the studio's collaboration with Steven Spielberg in 1988 on Who Framed Roger Rabbit. In many ways, that's the picture that restored interest among mainstream audiences in feature-length animated entertainment (or semi-animated, as it mixes live action with the cartoons). But Roger Rabbit, for all its many impressive virtues, is hardly in the Disney style.

That would be the job of The Little Mermaid. No doubt there are volumes of behind-the-scenes corporate backstory to this movie, involving industry players, gutsy business calls, and various career-making and -breaking maneuvers. It's also easy enough to pick out various elements and call "formula"—yet another princess story based on yet another Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale, yet another musical, and, as always, damnably cute more than 70% of the time. But in the end that's incidental to what ended up on the screen. In the watching, The Little Mermaid is one of those happy accidents where all pieces fall together and the result is something close to an ideal, achieved seemingly effortlessly.

Sunday, February 10, 2013

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007)

Junot Diaz's first novel, which followed a well-received collection of stories 11 years earlier, won a Pulitzer Prize and much acclaim, and it's not hard to see why. It's all voice and the voice is dazzling, steeped in Spanish idiom (heavy on the Dominican), youth argot, and nerd culture. It's the latter that impressed, amused, and amazed me most, pulling out Fantastic Four references as easily as Japanese anime as easily as fantasy role-playing games as easily as Star Trek—all Star Trek. I don't doubt that I missed more than half the references—they are sly, and constant, and it's a world that was only mine in passing, and never entirely so. When that wears thin (if it wears thin, and I don't think it does), Diaz turns with equal facility to political / economic / cultural history of the Dominican Republic, incidentally making the case for its nearly utter evaporation in world history. Thanks again, U.S. foreign policy! Oscar Wao thus bears a deceptively heavy burden. The propulsive momentum and the knack for highly charged and always engaging language reminded me more than once of Philip Roth. But the novel also seemed to me somewhat uneven and with nagging structural problems, most notably the place and purpose of the narrator, beyond his convenience as someone positioned to see it all and comment so richly on it. The story is most interesting to me when the main character, Oscar de Leon ("Wao" is a corruption of "Wilde" in a fanciful comparison to the literary giant), remains front and center. The necessity for plunging into Dominican history, often via lengthy footnotes but in whole sections of the book as well, eventually comes clear, but the novel did come perilously close to losing me here and there. Even the dazzling voice itself has some inconsistencies, shifting so much with Part II that I thought maybe a new narrator had come along. I suspect Diaz cares a good deal more about Dominican history than nerd culture—as, arguably, he should—but what I liked best about his writing is how much more firmly planted, and grounded, he feels as a nerd than as a Dominican. And I would say he's definitely one, as the usual mot has it, worth keeping an eye on.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, February 09, 2013

Don't Be Afraid of the Dark (1988)

Robert Cray's follow-up to Strong Persuader is a pretty good album, and the follow-up to that, 1990's Midnight Stroll, is not bad either, though I admit that's about where I stopped following along so closely. It's arguable that the public at large did not and does not think any such thing. In fact, nothing ever again came close to the success of Strong Persuader, which even produced a #22 hit in 1987 with "Smoking Gun." More than anything, that says something depressing about the commercial prospects of blues beyond an occasional novelty breakthrough, but that's not news to anyone at this point. Taken purely as product, I think Don't Be Afraid of the Dark is about nearly as good as it gets. There's a lot of work to do here but it's getting done: the vocals are adequate, the guitar playing is good—often outstanding, perhaps even better at its heights than Strong Persuader (the rave-up on "Across the Line," say). Most important, the songwriting is fine, still overwhelmingly concerned with lies, pain, and motel rooms, in interesting verse-chorus-verse forms and Memphis-tinged arrangements with horns. But, yeah, if I think about it enough, Don't Be Afraid of the Dark is a shade off Strong Persuader, I suppose. The stories aren't quite as interesting, swinging wild too often, lurid and unlikely. The vocal lines tend to blur off into the background that they occupy in most songs, seductive chanting and melody with no particular thing to say. "Your Secret's Safe With Me," for example, starts from the narrative strains Cray can be so good at, but feels a little lazy, ultimately settling for a B-movie blackmail trope that enters territories of distractingly unpleasant. So that's a shame. But at worst these are just problems of degree. The unique strengths of Strong Persuader are what make it good—and unique. After that it's just a matter of deciding where and how comfortable you are with Cray. For me he can fit like old shoes. I keep a Cray playlist and just let it rip on occasions, and that's how I know him best now. The songs from Strong Persuader often stand out, but they aren't the only ones, and not a few of the others are located here: "I Can't Go Home," "Night Patrol, "Laugh Out Loud." Some real winners here.

Friday, February 08, 2013

Shrek (2001)

USA, 90 minutes

Directors: Andrew Adamson, Vicky Jenson

Writers: William Steig, Ted Elliott, Terry Rossio, Joe Stillman, Roger S.H. Schulman, Cody Cameron, Chris Miller, Conrad Vernon

Production design: James Hegedus

Art direction: Guillaume Aretos, Douglas Rogers

Music: Harry Gregson-Williams, John Powell

Editor: Sim Evan-Jones

Cast/voices of: Mike Myers, Eddie Murphy, Cameron Diaz, John Lithgow, Vincent Cassel

What surprised me most about a revisit to Shrek is how dated it has become. (Full disclosure: though I saw Shrek when it was new, I have not since taken advantage of any of the offerings of the subsequent franchise, which include three sequels, five video games, various TV spinoffs, a comic book, and a Broadway musical.) I say this also acknowledging that many of its strengths are still there: taking a page out of The Princess Bride, it's as smart and knowing as ever about its sources, operates at both adult and kid levels, and tells its story with clarity, uncluttered by distraction. It's just complex enough to be interesting, it never cheats, and it is witty more often than gross (and even when it is gross, it is tame by today's standards).

One of the most obvious ways Shrek shows its age is also the one to be expected, which is the state of the art of the animation. I recall that the CGI here was considered one of its strong points on release, but now it just looks 12 years old—12 years that encompass a whole lot of innovation and development in the industry. Though it was conceived at one point in 3D, Shrek now seems to present-day animation somewhat as Hanna-Barbera of '70s TV was to it. But I don't make the finest distinctions among animation. The dated qualities of the Shrek CGI were enough for me to notice, but not enough to annoy. I would call Jay Ward one of my favorite animators and he's nothing if not primitive, so partly that's a matter of my own aesthetic. But another quality that dates Shrek is a bit more of an obstacle for me.

Directors: Andrew Adamson, Vicky Jenson

Writers: William Steig, Ted Elliott, Terry Rossio, Joe Stillman, Roger S.H. Schulman, Cody Cameron, Chris Miller, Conrad Vernon

Production design: James Hegedus

Art direction: Guillaume Aretos, Douglas Rogers

Music: Harry Gregson-Williams, John Powell

Editor: Sim Evan-Jones

Cast/voices of: Mike Myers, Eddie Murphy, Cameron Diaz, John Lithgow, Vincent Cassel

What surprised me most about a revisit to Shrek is how dated it has become. (Full disclosure: though I saw Shrek when it was new, I have not since taken advantage of any of the offerings of the subsequent franchise, which include three sequels, five video games, various TV spinoffs, a comic book, and a Broadway musical.) I say this also acknowledging that many of its strengths are still there: taking a page out of The Princess Bride, it's as smart and knowing as ever about its sources, operates at both adult and kid levels, and tells its story with clarity, uncluttered by distraction. It's just complex enough to be interesting, it never cheats, and it is witty more often than gross (and even when it is gross, it is tame by today's standards).

One of the most obvious ways Shrek shows its age is also the one to be expected, which is the state of the art of the animation. I recall that the CGI here was considered one of its strong points on release, but now it just looks 12 years old—12 years that encompass a whole lot of innovation and development in the industry. Though it was conceived at one point in 3D, Shrek now seems to present-day animation somewhat as Hanna-Barbera of '70s TV was to it. But I don't make the finest distinctions among animation. The dated qualities of the Shrek CGI were enough for me to notice, but not enough to annoy. I would call Jay Ward one of my favorite animators and he's nothing if not primitive, so partly that's a matter of my own aesthetic. But another quality that dates Shrek is a bit more of an obstacle for me.

Thursday, February 07, 2013

C

It doesn't take long for even the English alphabet to settle into signs of the all too human tendency to do things simply because "that's the way they've always been done" and "it's too late to stop now." The letter C, while possessed of a boldly simple, beautiful, and primal shape, nonetheless has no purpose, doing nothing that the letters S and K don't already do perfectly well (and combined with H it only produces a mouth noise that logically deserves its own letter). It's not—confining ourselves for the moment to consonants—the only letter to engage in such shenanigans. But it is the first. And at #12 overall in terms of frequency, C also happens to be the most often used of these variously "squishy" consonants (G, J, and X, with W and Y arriving late as particularly knotty problems). I know, I know, we're never going to get rid of the QWERTY (fun to type!) keyboard either. And truth be told, partly by its alphabetical prominence—supplying one more finish to one more short alphabet, in this case "ABCs," which my dictionary offers as a word with the definition "the rudiments of a subject"—partly by its comely shape, and partly by generations and centuries of simply acclimating to it, the otherwise ludicrous letter C offers a merely benign object now. I find I don't mind it much. Talk to a kid or ESL student, however, and you're apt to hear complaints. This multiplication of the sounds produced by a single letter, depending on the circumstances of its immediate neighbors on a case-by-case basis, is simply bad business. What, in the first place, do the hard and soft uses even have to do with one another? The first is a staccato noise made at the back of the throat (the "voiceless velar plosive"), the other is the most sibilant of all the sibilants. WTF C? A better case for hard and soft uses of a single letter could be made with the mouth noises produced by, respectively, P and B, T and D, or F and V. But no. The hard C is a K, the soft C is an S, end of argument. It's not even argument. It's instruction, and pedantic instruction at that. It's "the way we do it." Try to follow along. Followed by the vowels E or I (and sometimes Y, as in "cycle"), the C is soft (usually, though consider "soccer" or [some pronunciations of] "Celtic"). Otherwise the C is hard. Except for things like "muscle" or "Caesar." Good luck figuring out what C is doing in words like "luck" (definitively shortens the vowel?). To complicate (or komplikate) matters, an odd '60s gesture of defiance that occasionally persists is to spell hard Cs in specific instances (or specifik instances, maybe) with a K, most notably "Amerika." In a way I don't quite understand (perhaps something to do with Kafka), this is intended to signify opposition to fascism (and don't miss the uniquely weird C in that word). Conceivably it is also related to the Ku Klux Klan. Thus, while generally I am inclined toward sensible reklamation projekts in spelling where possible, I regret the unfortunate politikal implikations of this one, not that I would necessarily let it stop me. But you see the problem.

Wednesday, February 06, 2013

Kirsty MacColl, "Here Comes That Man Again" (2000)

(listen)

I know most of us are still not prepared to talk freely about cybersex among ourselves, but 13 years ago the late Kirsty MacColl gave it a perfectly charming, lighthearted whirl. It's fully marinated in the Cuban sounds and rhythms that mark the album it comes from, Tropical Brainstorm (see also). It's dated, to be sure, lurching out of what suddenly now appear to be more innocent times, the late '90s. You don't hear modem tones so much anymore, for one thing, and "get your rocks off" goes back even further to the era of "humping." But this shticky number sketches the screaming weirdness with almost clinical precision, sighing contentedly at one point, "Who'd have thought I'd have so much fun ... I never knew I had it in me." She always treads lightly, but seems to have the basics right: "oops, another file on the email, oh oh-oh ohh," so on so forth. The compulsion, the payoffs, the many surprises, not all good. It's extremely silly, nearly as silly as it is intoxicating, thus a topic perfectly suited to her style of songwriting. Through the swirl of rhythms and arrangement, broad sound gags bubble up and charge the energy, such as a wacky muted trumpet that serves as ba-da-boom for one of the punch lines. There's a Monica Lewinsky joke too, in the thick of the big finish, which lets loose with a tattoo of "sha la la la la, get your rocks off baby." This may or may not be my favorite song by Kirsty MacColl but everything I like about her is in it: it's equally funny and poignant and fearless, and musically it's Tin Pan Alley sophisticated with an eye on the rest of the world and winning popcraft all the way.

I know most of us are still not prepared to talk freely about cybersex among ourselves, but 13 years ago the late Kirsty MacColl gave it a perfectly charming, lighthearted whirl. It's fully marinated in the Cuban sounds and rhythms that mark the album it comes from, Tropical Brainstorm (see also). It's dated, to be sure, lurching out of what suddenly now appear to be more innocent times, the late '90s. You don't hear modem tones so much anymore, for one thing, and "get your rocks off" goes back even further to the era of "humping." But this shticky number sketches the screaming weirdness with almost clinical precision, sighing contentedly at one point, "Who'd have thought I'd have so much fun ... I never knew I had it in me." She always treads lightly, but seems to have the basics right: "oops, another file on the email, oh oh-oh ohh," so on so forth. The compulsion, the payoffs, the many surprises, not all good. It's extremely silly, nearly as silly as it is intoxicating, thus a topic perfectly suited to her style of songwriting. Through the swirl of rhythms and arrangement, broad sound gags bubble up and charge the energy, such as a wacky muted trumpet that serves as ba-da-boom for one of the punch lines. There's a Monica Lewinsky joke too, in the thick of the big finish, which lets loose with a tattoo of "sha la la la la, get your rocks off baby." This may or may not be my favorite song by Kirsty MacColl but everything I like about her is in it: it's equally funny and poignant and fearless, and musically it's Tin Pan Alley sophisticated with an eye on the rest of the world and winning popcraft all the way.

Tuesday, February 05, 2013

So You Think You Can Review Tournament: Introduction

A couple of years ago, in the usual blog-related effort to drum up traffic and interest, I joined the Large Association of Movie Blogs (LAMB). I had the best intentions of participating in the various blogathon types of things they do and I even stuck with it awhile. For reasons both good and bad I drifted away. But last summer a bracket-style tournament was announced and somehow caught my attention. Against my better judgment I decided to give it a try—"better judgment" because I had to question why I was doing it: traffic, more readers, more attention, general egotistical shoring-up, that kind of thing. A lot of the familiar what-is-this-vanity-project-why-am-I-blogging-anyway questions. At the same time, I had a fair amount of natural anxiety about undue competitiveness and losing. But it seemed like an interesting challenge so I decided to go for it.

The original field was 32 reviewers. In the interests of fairness, attempts were made to keep and preserve anonymity. We had to go by pseudonyms (I was "Botch Casually") and the organizer, Nick of Random Ramblings of a Demented Doorknob, went to pains to ensure the movies we were assigned to review had not been reviewed previously on our blogs. That alone is going above and beyond. But I also thought his movie picks for us were always interesting, difficult, maddening, and fair, designed to throw us equally out of our various comfort zones. Here's an overview of how it was set up.

What I'm going to do here over the next weeks is reproduce my review entries, starting with the first round and taking it as far as I got. I'll also have links to my competitor's review, in the original post with mine, along with comments and the voting results. Judge for yourself who should or should not have won! And of course I will then have to step in with the chin-stroking afterword. It all starts next week! (Also, so you know, I didn't use my usual headers for the tournament submissions but I will be adding them for publication here.)

The original field was 32 reviewers. In the interests of fairness, attempts were made to keep and preserve anonymity. We had to go by pseudonyms (I was "Botch Casually") and the organizer, Nick of Random Ramblings of a Demented Doorknob, went to pains to ensure the movies we were assigned to review had not been reviewed previously on our blogs. That alone is going above and beyond. But I also thought his movie picks for us were always interesting, difficult, maddening, and fair, designed to throw us equally out of our various comfort zones. Here's an overview of how it was set up.

What I'm going to do here over the next weeks is reproduce my review entries, starting with the first round and taking it as far as I got. I'll also have links to my competitor's review, in the original post with mine, along with comments and the voting results. Judge for yourself who should or should not have won! And of course I will then have to step in with the chin-stroking afterword. It all starts next week! (Also, so you know, I didn't use my usual headers for the tournament submissions but I will be adding them for publication here.)

Monday, February 04, 2013

seenery

Movies/TV I saw last month...

All That Jazz (1979)—I have always admired this but never particularly connected with it. And I definitely don't think it is Fosse's best—I put Cabaret and also Lenny ahead of it.

Atlantic City (1980)—Another one that had eluded me. I thought it was excellent. Both Susan Sarandon and Burt Lancaster are so great, and I loved all the ins and outs of the story. Also, it looked great, a European film overlay on top of Atlantic City in the middle of being demolished and rebuilt in the '70s.

The Bakery Girl of Monceau (1962)—This is the first of Eric Rohmer's Moral Tales, a thematic series of six movies, the first two of which are less than 60 minutes. All six involve a man, always a different man, choosing between two women, always different women. The Criterion box (typically an excellent product, if pricy) also has a bunch of other shorts scattered along the way, all with Rohmer's fingerprints: Veronique and Her Dunce (1958), Presentation, or Charlotte and Her Steak (1960, featuring Jean-Luc Godard), Nadja in Paris (1964), On Pascal (1965), A Modern Coed (1966), The Curve (1999). They are all variously elliptical and charming. Bakery Girl, which stars Barbet Schroeder, fits more closely with them, in many ways, because of its brevity at only 23 minutes.

Bernie (2011)—I think we already knew what a good singer Jack Black is and I was generally not as impressed with him here as it sounds like others are. But Linklater tends to be worth revisiting and it's possible this will get better.

The Big Country (1958)—I have to admit my heart sank a little when I saw this William Wyler Western was nearly three hours long, but wow, it's pure entertainment. Big story, big landscape (of course), big everything, and always engaging. I loved Gregory Peck too. This makes me pretty sure at least two more Wylers I haven't seen are probably due for bumping up.

Civilisation (1969)—Finishes strong even given his general inability to deal with 20th century art.

Claire's Knee (1970)—Another high point of Eric Rohmer's Moral Tales, the fifth in the series, though in our age (perhaps, or perhaps it's me) it seems a little too unnervingly fascinated by pubescent girls, viz., the title.

Cloud Atlas (2012)—Disappointing mess, I'm sorry to say.

La Collectionneuse (1967)—I think this is my favorite of Eric Rohmer's Moral Tales, which I'm willing to believe is because Haydee Politoff is such a perfectly enigmatic (and beautiful) young woman. Strangely, this picture feels bare bones low-budget and lushly rich at the same time—something about the way color is used.

Cosmopolis (2012)—Occupy David Cronenberg by way of a 2003 Don DeLillo novel. Not bad.

Coup de Torchon (1981)—Yeah, not sure transposing Jim Thompson to Africa is such a good idea, but nice try.

All That Jazz (1979)—I have always admired this but never particularly connected with it. And I definitely don't think it is Fosse's best—I put Cabaret and also Lenny ahead of it.

Atlantic City (1980)—Another one that had eluded me. I thought it was excellent. Both Susan Sarandon and Burt Lancaster are so great, and I loved all the ins and outs of the story. Also, it looked great, a European film overlay on top of Atlantic City in the middle of being demolished and rebuilt in the '70s.

The Bakery Girl of Monceau (1962)—This is the first of Eric Rohmer's Moral Tales, a thematic series of six movies, the first two of which are less than 60 minutes. All six involve a man, always a different man, choosing between two women, always different women. The Criterion box (typically an excellent product, if pricy) also has a bunch of other shorts scattered along the way, all with Rohmer's fingerprints: Veronique and Her Dunce (1958), Presentation, or Charlotte and Her Steak (1960, featuring Jean-Luc Godard), Nadja in Paris (1964), On Pascal (1965), A Modern Coed (1966), The Curve (1999). They are all variously elliptical and charming. Bakery Girl, which stars Barbet Schroeder, fits more closely with them, in many ways, because of its brevity at only 23 minutes.

Bernie (2011)—I think we already knew what a good singer Jack Black is and I was generally not as impressed with him here as it sounds like others are. But Linklater tends to be worth revisiting and it's possible this will get better.

The Big Country (1958)—I have to admit my heart sank a little when I saw this William Wyler Western was nearly three hours long, but wow, it's pure entertainment. Big story, big landscape (of course), big everything, and always engaging. I loved Gregory Peck too. This makes me pretty sure at least two more Wylers I haven't seen are probably due for bumping up.

Civilisation (1969)—Finishes strong even given his general inability to deal with 20th century art.

Claire's Knee (1970)—Another high point of Eric Rohmer's Moral Tales, the fifth in the series, though in our age (perhaps, or perhaps it's me) it seems a little too unnervingly fascinated by pubescent girls, viz., the title.

Cloud Atlas (2012)—Disappointing mess, I'm sorry to say.

La Collectionneuse (1967)—I think this is my favorite of Eric Rohmer's Moral Tales, which I'm willing to believe is because Haydee Politoff is such a perfectly enigmatic (and beautiful) young woman. Strangely, this picture feels bare bones low-budget and lushly rich at the same time—something about the way color is used.

Cosmopolis (2012)—Occupy David Cronenberg by way of a 2003 Don DeLillo novel. Not bad.

Coup de Torchon (1981)—Yeah, not sure transposing Jim Thompson to Africa is such a good idea, but nice try.

Sunday, February 03, 2013

Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986)

It's more important than ever nowadays to keep your Dark Knights straight so here's a way to help you remember. This is the original and this is the best. No other comic book, let alone any movie, touches it. You don't have to think about anything else but this. When you have finished it, go ahead and try some of the others. If you start to feel confused again, return immediately to this one. It's really as simple as that. All those post-'60s-TV-show attempts to salvage Batman from the insipid pop culture mainstream that catapulted him to exactly the wrong renown (such attempts usually signaled by a heavy-handed insistence on the definite article, e.g. "Looks like trouble, we'd better get the Batman") came to naught—as worthy as they were, notably when Neal Adams started illustrating them—until Miller definitively reimagined the strangely enduring figure as a washed-up, middle-aged, has-been alcoholic, suffering the aches and pains of too many late-night fistfights, too many bone-crushing falls of failed acrobatics, and way too much boozing. The Robin in this adventure is a punk-rock chick with various problems. The Joker is a stone-cold psychopath. Superman is a contemptible do-gooder. And our old friend Bruce Wayne is slow, angry, thickened up in the middle, and not always thinking straight. At a stroke, Miller returned the Batman to everything people used to claim he should be. I was skeptical going in, I had heard this before, but this graphic novel is practically guaranteed to change the way people think, and it worked for me. Miller followed this up with Batman: Year One, which reimagined the origin story with equal potency and locked in the modern conception of our favorite superhero with no superpowers. Everybody since then has just been trying to keep up, whether that's Tim Burton or Christopher Nolan in the movies, or the rafts of writers and artists for the comic book and its rejuvenated potential for spinoffs. In this conception, likely best known now from the Nolan movie adaptations, Batman has become more of a psychopath himself, albeit one ostensibly for our side, a loner and vigilante who never recovered from the trauma of seeing his parents killed in a street stick-up, who comes most alive at night attacking prowlers and other bad guys. He's not fun, but he's often impressive, awe-inspiring even, which can get to be just about as good as fun. Miller's story and art (with inks by Klaus Janson, his future partner on the Daredevil franchise for Marvel) are never less than compelling, with their bleak, unified, and nearly perfectly realized vision of a media-saturated Gotham City in decline, and the scary grizzled drunk in cape and cowl who has appointed himself judge and jury of the place after nightfall.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, February 02, 2013

Strong Persuader (1986)

By consensus, by acclimation, by the rule of all that is obvious, Robert Cray's breakthrough fifth album (counting Showdown!) is his best. You can almost measure and compare the love Cray fans have for it by how many other albums by him they have had occasion to own (on that scale I am at about a 6). But I have never yet known anyone to claim another by him as better. The template for everything that makes him great is here in these 10 songs, where in retrospect he is clearly about the business of taking down low-hanging fruit. As a guitar player, he's perfectly adequate, even given to moments of brilliance; as a singer it's about the same, though closer to merely adequate. What's most interesting about Robert Cray to me is his songwriting, and more generally and broader than that, the way he builds songs, the story elements he uses. So many of these songs are practically literary, a voice carrying on with a story but somehow also conveying a broader context that often belies, or undercuts, or sometimes emphasizes what the singer is carrying on about. In "Guess I Showed Here," a guy is crowing to himself about all the pain he is causing his woman by leaving her, because he thinks she is having an affair. But he sounds less and less convinced, mulling in the last verse, "Now she can have the house / And she can keep the car / I'm just satisfied / Staying in this funky, little old motel / I'm so mad / Well I can't stand it." In "Right Next Door (Because of Me)," even more starkly, the singer hears the woman he has seduced fighting with her man in the apartment next door (more here). Another element of Cray's songwriting becomes evident comparing the two. He does not have just one persona, nor just a single story, to tell. There's a multiplicity to these songs—which may not have a single story to tell, but ultimately all tend to connect one way or another around deceit in matters of love—that reminds me of a parallel multiplicity to mid-'60s albums by the Beatles. In those songs it is puppy love whereas Cray's are sophisticated and cynical, but the same shifting viewpoints across horizons of experience within the stories of the songs is there. So one result for me is that, as I return to Strong Persuader now and then, I notice that different songs step out differently from the others, or rub against each other in new and different ways, and I identify with these narrators in different ways. It still can seem new when I come back to it. One constant always, of course, is that these songs are excellent blues jam workups within the verse-chorus-verse structure and a perfect pleasure to let just play.

Friday, February 01, 2013

Ran (1985)

Japan/France, 162 minutes

Director/editor: Akira Kurosawa

Writers: Akira Kurosawa, Hideo Oguni, Masato Ide, William Shakespeare

Photography: Asakazu Nakai, Takao Saito, Shoji Ueda

Music: Toru Takemitsu

Cast: Tatsuya Nakadai, Mieko Harada, Akira Terao, Jinpachi Nezu, Daisuke Ryu, Pita, Masayuki Yui, Yoshiko Miyazaki, Mansai Nomura

Akira Kurosawa's late grand epic, made when he was 75, can serve today as one self-contained clinic in The Big Movie, the sweeping, ponderous exercises that swallow one whole, with story, with image, with music and color and faces and event. They come in many shapes and sizes, of course (nearly always long), and Ran is only one. It is filled with gravitas, riffing equally on classic Japanese jidaigeki and Shakespeare and matters of great moral and personal moment, at the highest and lowest levels of power. At the same time it occupies an exclusive cinematic space defined across the decades of Kurosawa's career. Perhaps most surprising, it is capable of a convulsive, headlong narrative momentum.

I think that's probably the Shakespeare, of course, the famous Western streak of Kurosawa. I don't know King Lear, the Shakespeare story adapted here, but I recognize the complexities and symmetries of the storytelling, which has biblical strains as well in its primary narrative arc of spiteful sons and stupid father. It has two remarkable characters: first the stupid father, the warlord Hidetora (Tatsuya Nakadai), and then his daughter-in-law Kaede (Mieko Harada). They share a complicated background that plays out by proxy, the ghost of their conflict haunting the epic battle scenes for which this picture is rightly famous. Ran is another fine example, perhaps the last so purely, of Kurosawa's never-ending adroit balancing act of self-consciousness, between East and West, privation and privilege, pageantry and naturalism, theater and cinema, war and peace, life and death and the spirit world.

Director/editor: Akira Kurosawa

Writers: Akira Kurosawa, Hideo Oguni, Masato Ide, William Shakespeare

Photography: Asakazu Nakai, Takao Saito, Shoji Ueda

Music: Toru Takemitsu

Cast: Tatsuya Nakadai, Mieko Harada, Akira Terao, Jinpachi Nezu, Daisuke Ryu, Pita, Masayuki Yui, Yoshiko Miyazaki, Mansai Nomura

Akira Kurosawa's late grand epic, made when he was 75, can serve today as one self-contained clinic in The Big Movie, the sweeping, ponderous exercises that swallow one whole, with story, with image, with music and color and faces and event. They come in many shapes and sizes, of course (nearly always long), and Ran is only one. It is filled with gravitas, riffing equally on classic Japanese jidaigeki and Shakespeare and matters of great moral and personal moment, at the highest and lowest levels of power. At the same time it occupies an exclusive cinematic space defined across the decades of Kurosawa's career. Perhaps most surprising, it is capable of a convulsive, headlong narrative momentum.

I think that's probably the Shakespeare, of course, the famous Western streak of Kurosawa. I don't know King Lear, the Shakespeare story adapted here, but I recognize the complexities and symmetries of the storytelling, which has biblical strains as well in its primary narrative arc of spiteful sons and stupid father. It has two remarkable characters: first the stupid father, the warlord Hidetora (Tatsuya Nakadai), and then his daughter-in-law Kaede (Mieko Harada). They share a complicated background that plays out by proxy, the ghost of their conflict haunting the epic battle scenes for which this picture is rightly famous. Ran is another fine example, perhaps the last so purely, of Kurosawa's never-ending adroit balancing act of self-consciousness, between East and West, privation and privilege, pageantry and naturalism, theater and cinema, war and peace, life and death and the spirit world.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)