The Earrings of Madame de..., France / Italy, 105 minutes

Director: Max Ophüls

Writers: Louise de Vilmorin, Marcel Achard, Max Ophüls, Annette Wadamant

Photography: Christian Matras

Music: Oscar Straus, Georges Van Parys

Editor: Boris Lewyn

Cast: Charles Boyer, Danielle Darrieux, Vittorio De Sica, Lea di Lea, Jean Debucourt

A hasty internet search this morning failed to reveal the circumstances of the title change for the American release of this movie (to The Earrings of Madame de...). So I don't know who did it or why. What's interesting is how it subtly yet effectively alters the prevailing frame, from a wry focus on the upper-class foibles of the elaborately unnamed protagonist, which is appropriate, to a focus rather on a classic cinematic "MacGuffin," a plot device of an object in which all characters have an interest, but which otherwise has little point. The statue in The Maltese Falcon is a classic MacGuffin.

Just so, the earrings in question, which appear in the first and last shots of this movie, are a notably busy kind of MacGuffin all through, moving from the possession of one character to another over a dozen times, which is taken to a particular point in the second half where credulity itself begins to be strained. It's easy to be distracted by them, so easy that you might be tempted to feature them in a retitle for midcentury American audiences. But this MacGuffin actually has meaning—many meanings. The earrings are always a reflection of any character in possession of them at the moment they have them, and always further receding reflections in an opposing mirror of Madame de (we never quite catch her name though it comes up now and again, concealed presumably as a matter of valor or at least discretion). At first the Madame finds the earrings ugly, when she is deciding to sell them to pay off illicit debts. Later, when she can no longer possess them, she will love them with all her heart.

Friday, December 30, 2016

Madame de... (1953)

Monday, December 26, 2016

The Handmaiden (2016)

As it happens, I overheard numerous complaints all week in real life and on Facebook about the length of The Handmaiden: cautions that it was long, real-time anguish from someone realizing too late he had arrived at a long movie, even bathroom jokes, etc. So heads up everybody. The Handmaiden is well over two hours, at 144 minutes, and it's good to be prepared, as it moves at a leisurely pace. I thought it was ravishing good fun, not referring specifically to the generous sex scenes, and I got a great big kick out of the way it clanked and swooped along. It's funny and harrowing and full of surprises. It's divided into three parts, the first two of which advance and bend reality in a show of literary legerdemain, as Park likes to do it. What you see is not always what you get, and I really shouldn't say more than that. A Japanese woman engaged to her uncle takes a handmaiden, who is part of an elaborate scheme—bup bup! That's all I can say. I've seen a couple of other pictures by Korean director and cowriter Chan-wook Park, most notably Oldboy, probably his most famous, as well as I'm a Cyborg, But That's OK, which is more in the way of a throwaway. What I like most about The Handmaiden is how much it feels like a big swooning novel, at pains to yoke together two separate narrative styles—the British gothic as in Wuthering Heights or Oliver Twist combined with a Japanese chamber drama about love and deceit. So at pains is Park to emphasize this double whammy that he sets it in a mansion which is itself half English countryside manor and half Japanese villa. In Korea. By obvious careful design. I'm sure a lot of cultural business between Japan and Korea, and England too, sailed right over my head—among other things, it's set in the 1930s, when Korea was occupied by Japan. The subtitles are careful to distinguish the two languages, and the circumstances under which either is spoken in the story carry many ambiguous meanings. In the third section the whole thing becomes a bit of a runaway happy ending train, but that's just the kind of thing we need at this time of year, innit? Along with, for the delectation of the male gaze, a bunch of reasonably hot lesbian sex scenes. Also, it wouldn't be complete without shocking violence, so look out for that too. If I'm going to complain about this, and I really don't want to, it's more about the tidy wrap-up. I liked it more in the first two sections when it was sprawling and opening wider and wider and the ground was always shifting. Park is good at that, and this movie is a pretty good time. Have you heard that it's long?

Sunday, December 25, 2016

"Redemption" (1977)

Read story by John Gardner online.

John Gardner's story starts out really well, delivering on the promise of the title with a minimum of fuss, but ends in a strange place. Jack Hawthorne is 12 and he unintentionally kills his 7-year-old brother David in a horrific accident involving farm machinery. That's the first thing we learn, and from there it is no problem to make a need for redemption believable. Jack's father goes to pieces, drinking and carousing and disappearing from home for days and weeks at a time. His mother is more stoic but she is broken too. It's arguably worst of all for Jack. No one blames him—it was a foolish avoidable accident, but an accident—except himself. This is the basic thrust, and it's powerful, based on an incident in Gardner's own life. But the details at the edges are weird and distracting. His father is some kind of poet-farmer, appearing at functions to read and entertain. They are in the country, on a farm, but it feels distinctly urban, or at least suburban. Maybe exurban? Somehow it feels like Ben & Jerry's Vermont. The unfocused and confusing setting only becomes worse when it becomes evident how Jack will redeem himself—by learning to play the French horn from an Old World master. Each element on its own might be convincing, but in the totality they are in conflict with one another. Jack works hard on the farm and also goes to a good school, a modern urban public school. If there's a certain disconnect between how hard and seriously Jack and his father work on the farm, it's even more so when the Old World master and French horn come along. Again, it's convincing enough, in this section, about the wonders and beauties and so forth of music, but it is jarringly at odds with what has gone before. Step back and think about it, and I suppose maybe it makes sense that a poet-farmer would raise a son who finds redemption playing the French horn, but they both feel so outside the norm I don't even know where to start. Their relationship is murky enough as it is, distorted by the tragedy. After the accident Gardner starts to lose me right away and by the introduction of the Old World master I was about gone, though the language is captivating enough to keep it going. This story qualifies for that great bland insult of any fiction, "It's well written." It feels more like a lost opportunity to me.

American Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks

John Gardner's story starts out really well, delivering on the promise of the title with a minimum of fuss, but ends in a strange place. Jack Hawthorne is 12 and he unintentionally kills his 7-year-old brother David in a horrific accident involving farm machinery. That's the first thing we learn, and from there it is no problem to make a need for redemption believable. Jack's father goes to pieces, drinking and carousing and disappearing from home for days and weeks at a time. His mother is more stoic but she is broken too. It's arguably worst of all for Jack. No one blames him—it was a foolish avoidable accident, but an accident—except himself. This is the basic thrust, and it's powerful, based on an incident in Gardner's own life. But the details at the edges are weird and distracting. His father is some kind of poet-farmer, appearing at functions to read and entertain. They are in the country, on a farm, but it feels distinctly urban, or at least suburban. Maybe exurban? Somehow it feels like Ben & Jerry's Vermont. The unfocused and confusing setting only becomes worse when it becomes evident how Jack will redeem himself—by learning to play the French horn from an Old World master. Each element on its own might be convincing, but in the totality they are in conflict with one another. Jack works hard on the farm and also goes to a good school, a modern urban public school. If there's a certain disconnect between how hard and seriously Jack and his father work on the farm, it's even more so when the Old World master and French horn come along. Again, it's convincing enough, in this section, about the wonders and beauties and so forth of music, but it is jarringly at odds with what has gone before. Step back and think about it, and I suppose maybe it makes sense that a poet-farmer would raise a son who finds redemption playing the French horn, but they both feel so outside the norm I don't even know where to start. Their relationship is murky enough as it is, distorted by the tragedy. After the accident Gardner starts to lose me right away and by the introduction of the Old World master I was about gone, though the language is captivating enough to keep it going. This story qualifies for that great bland insult of any fiction, "It's well written." It feels more like a lost opportunity to me.

American Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks

Friday, December 23, 2016

Schindler's List (1993)

USA, 195 minutes

Director: Steven Spielberg

Writers: Thomas Keneally, Steven Zaillian

Photography: Janusz Kaminski

Music: John Williams

Editor: Michael Kahn

Cast: Liam Neeson, Ben Kingsley, Ralph Fiennes, Caroline Goodall, Jonathan Sagall, Embeth Davidtz, Malgorzata Gebel, Shmuel Levy, Mark Ivanir

At the time Schindler's List was new I was not entirely on board with the larger Spielberg project and I focused more on the problems I saw with the picture. I'm a little more on board now, and can see I missed a lot of what makes it arguably a great movie. There are great performances and its commitment to showing what the Holocaust and the German Nazi regime looked like is unstinting, the main reason the movie is so long and rated R ("contains some adult material"). It is ambitious about telling a simple, resonant story of the Holocaust, and erecting a broad sweeping vision of that context—the systematic abuse and murder of some 6 million Jews by German Nazis in the 1930s and 1940s.

Schindler's List is good, even great, because it doesn't flinch from showing the details. It learned well from Shoah the stories of what happened in the Holocaust. Shots and scenes in Schindler's List are often reminiscent of what we came to understand from the massive 1985 documentary and elsewhere. And yet, something nags at me when I look at Schindler's List. The movie often seems bloated and gaseous in memory, over-swamped by the excesses of its own good intentions somehow. I don't doubt the veracity but it often feels exaggerated for effect. And I still see the problems I've always seen with it. They still work to undermine the movie's best intentions and strengths. They aren't big problems, in terms of screen time generally, but somehow they puncture it, almost irreparably.

Director: Steven Spielberg

Writers: Thomas Keneally, Steven Zaillian

Photography: Janusz Kaminski

Music: John Williams

Editor: Michael Kahn

Cast: Liam Neeson, Ben Kingsley, Ralph Fiennes, Caroline Goodall, Jonathan Sagall, Embeth Davidtz, Malgorzata Gebel, Shmuel Levy, Mark Ivanir

At the time Schindler's List was new I was not entirely on board with the larger Spielberg project and I focused more on the problems I saw with the picture. I'm a little more on board now, and can see I missed a lot of what makes it arguably a great movie. There are great performances and its commitment to showing what the Holocaust and the German Nazi regime looked like is unstinting, the main reason the movie is so long and rated R ("contains some adult material"). It is ambitious about telling a simple, resonant story of the Holocaust, and erecting a broad sweeping vision of that context—the systematic abuse and murder of some 6 million Jews by German Nazis in the 1930s and 1940s.

Schindler's List is good, even great, because it doesn't flinch from showing the details. It learned well from Shoah the stories of what happened in the Holocaust. Shots and scenes in Schindler's List are often reminiscent of what we came to understand from the massive 1985 documentary and elsewhere. And yet, something nags at me when I look at Schindler's List. The movie often seems bloated and gaseous in memory, over-swamped by the excesses of its own good intentions somehow. I don't doubt the veracity but it often feels exaggerated for effect. And I still see the problems I've always seen with it. They still work to undermine the movie's best intentions and strengths. They aren't big problems, in terms of screen time generally, but somehow they puncture it, almost irreparably.

Monday, December 19, 2016

Manchester By the Sea (2016)

Even though he's only made three features now to date, Manchester By the Sea director and writer Kenneth Lonergan is one of my favorites. You Can Count on Me is that good, and Margaret is not bad either for a commercially buried studio botch job. Happy then to find that even with highest expectations Manchester By the Sea is one of the best things I've seen in a long while. Once again strained family relations are the focus—it's more pages ripped from that safe place we all go where it hurts. Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts, is the setting, a small town on the Atlantic coast of about 5,000. Casey Affleck is Lee Chandler, a single man working for minimum wage and a room as a building maintenance man in a Boston apartment complex. It's just an aces script. Things happen right along—first off, Lee hears that his brother Joe (Kyle Chandler, no relation) has died at age 45 from a known heart condition. Lee has to go back to Manchester to take care of affairs. He learns at the reading of the will that Joe has designated and provided for him as the legal guardian of Joe's son, Lee's nephew, Patrick (Lucas Hedges). This is not something Lee saw coming, though steady flashback sequences have begun to establish their long-term relationship, and all the swirling events that mark him and his brother and his family. Lee, actually, has quite a lot of baggage from his past, including a former marriage with Randi (Michelle Williams). It's a bit of a jam in the first 40 minutes or so getting the context and details fleshed out. There's a lot of whispering and murmuring from the townsfolk signifying something big. Thankfully, they get to that soon enough that we don't have to be too annoyed with teasing. There are some overdone scenes here—Lesley Barber really sets the orchestra to sawing in a couple of key sequences. But I can't say I wasn't unaffected—it's got a pinch of Mystic River hysterics, but that's reined in enough. It's mostly a showcase for Casey Affleck, who may or may not be underrated, but whose only performance even close to this I know was the underrated Assassination of Jesse James. He is also drawing a lot from Mark Ruffalo's turn in You Can Count on Me (or maybe that's Lonergan's direction). Michelle Williams has relatively little screen time but she's there for every second of it. The best scenes, and there are a few of them, involve a stationary camera, a room, and long, long awkward passages. There is death and tragedy here (and that sawing orchestra too) but it didn't feel too overdone, once acclimated to the premise. Everyone is up for this. I want to see it a bunch more times.

Sunday, December 18, 2016

Grown Up All Wrong (1998)

Rather than his own joking self-appellation, the "Dean of American Rock Critics," I tend to think of Robert Christgau more as the Pete Rose of American rock critics. That's for his capsule album reviews, which now number well over 12,000 and counting. And even though I'd bet Rose makes it into his hall of fame before Christgau makes it into his, no one else has accomplished anything like it. Still, I think I get more of everything I like about Christgau these days in his longer pieces, as found in this oversize encyclopedia volume collection from the turn of the century, which feels like a summary statement. It's as thoroughgoing an exercise as one could hope for from the man with perhaps the most catholic tastes in all rock, pop, and beyond. He brings a useful perspective to Elvis Presley, casting him as a literary hero. He has one of the best single paragraphs I've ever encountered on the Beatles (short form, he can't quit you). And there is nothing at all specifically about Bob Dylan. Certain points of his taste are blind spots for me I already know about: the New York Dolls, Loudon Wainwright III, and some others. More often I appreciate the insights. His piece on James Brown, when I first read it years ago, opened the whole world of Brown to me, or somehow emboldened me to explore deep into Brown's strange and massive catalog. Christgau's Nirvana sendoff isn't any more flinty than it needs to be, and hits a good many notes. And the pieces about African music represent an interesting shift in his voice, more evangelist than anywhere else in his writing, and obviously researched with backstories and context because he knows his readers are unlikely to bring it themselves. As it happens, this fights a little with another instinct of his, which is to be the casual wiseacre smartest guy in the room catcalling from the sidelines, an impulse that runs to some excesses here in spots. That's in his capsule reviews too. He can't help himself. He goes out of his way to insult people by name—academics he doesn't trust, various taste makers, and sundry other figures lodged in his craw. Notwithstanding, it's a great bunch of thoughtful essays, even on artists you might not care that much about. He cares, and he's here to tell you why, and that's just infectious enough. It's a big book but worth going through slowly and carefully—among other things, more opportunities for list making and further shopping / streaming considerations. A consumer guide, you might say even. Christgau thinks so hard and so clearly about what he hears that he has the ability to make me think differently about things I've heard all my life, like James Brown.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Monday, December 12, 2016

Allied (2016)

Brad Pitt is back to killing stinking Nazis and there are many details about this movie I am honor-bound to conceal from you. It's a World War II movie about spies set in Casablanca, wishing very hard that it could be the movie Casablanca, which if you will recall had numerous false endings in the delicious pile-up at the end. So mum's the word bub. With director Robert Zemeckis running the show (Back to the Future, Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Forrest Gump), there was bound to be at least a little blast of the meta in Allied. Brad Pitt is Max Vatan, of Medicine Hat, Alberta, a special operations man for the British. Marion Cotillard is Marianne Beausejeur of Paris, a French Resistance fighter. The first half, set in yes French Moroccan Casablanca, is about their mission to assassinate a German ambassador. They fall in love, the mission is a spectacular success (maybe 15 or more visible Nazi kills), and they decide to get hitched in London. Ain't love grand? They have a baby—outdoors, actually, during a German bombing raid. Yes, of course it's overdone, but wait till you see the spectacle of the bombing planes, probing searchlights, giving birth, antiaircraft fire, and even a dirty Nazi plane brought right down to the ground. Huzzah! Next thing you know, Marianne is officially under suspicion by the British military of being a filthy German spy. Well, there's the central conflict for you, and now I must refrain from saying any more. I can tell you it's a pretty good show, tightly written, propulsive, and nearly always interesting. There's some flab around the end of the second third that could get it under two hours if they cared, maybe 20 or so uninteresting minutes. Pitt is solid with his middle-aged Robert Redford shtick which suits him fine. I haven't actually seen that much of Cotillard before but she's fine here too as a sultry dark and mysterious beautiful European woman. My favorite parts were in the first half in Casablanca. It was not at all like the city in the 1942 picture but much more naturally exotic and atmospheric, with strange sights and sounds and ways. The black, red, and white Nazi insignia never fails to fill me with dread and loathing and there's plenty of that here too. In fact, this movie is for anyone who enjoys seeing Nazis killed dead, not to mention an almost swell love story. Not bad.

Sunday, December 11, 2016

Popular Crime (2011)

I was familiar with Bill James before I lost interest in baseball, and with some idea of his stature there (still growing I believe), but reviews of his lengthy meditation on true crime literature made me wary in advance. It's true that James attempts some statistical analysis here, much of which is just kind of silly, and also that he has some strange and alienating ideas. But who doesn't, in this realm? He is as much a wonderful read as ever when he enters into certain free-flowing yet steady currents of thought. First, I really appreciate his appreciation of true crime literature itself, in all its low-class stigma and strange and often badly written glories. Among other things I was happy to find James completely at ease in one of its greatest attractions: second-guessing everyone in sight. The police, prosecutors, and media, of course, of course, of course, and in approximately that order. Also juries and suspects. Anyone, literally. Anything that looks remotely suspicious from the vantage of reading a book in your living room trying to figure out how these blasted crimes happen and investigations go so wrong and it all becomes mysterious and deeply knowable-yet-unknowable, like the tricks of stage magicians, eternally nagging away. Plus human primal drama by the gallon—really. At its most base it is probably outrage porn that draws many, but that doesn't make it any less profound or fascinating or repulsive. My particular interests diverge some from James's so he has missed some obvious cases by my lights, such as the West Memphis Three, but often enough he is on to cases and books I hadn't known. It wasn't long before my secondary mission was grabbing titles, authors, and cases for future binges.

I thought James looked most silly (recognizing many others in baseball have seen him as silly and been wrong) attempting to elucidate the paradoxes of Lizzie Borden with a weird point system. I liked his theory of the JFK assassination, that the magic bullet was the accidental firing of a Secret Service gun, because why not? He seems worst to me on '60s crime more generally, veering toward Jack Webb territory with strained theories about liberals, hippies, and especially the Earl Warren Supreme Court. That theme became shrill for me and made me like or trust him less. On the other hand, we are broadly in agreement about the literature. Yes, it is full of ugly photos, bad writing, and human depravity. But it is actually about the most vital and profound issues: life, death, and judgment. Back of that, however, maddeningly, down in the nitty-gritty of the crimes and investigations, it starts to look like the bizarre subatomic world of physics, where forces are at work, but we don't understand them. That's what's so fascinating. We're not always even sure what happened. Thus, for example, the class of cases where people, such as Tim Masters in Fort Collins, Colorado, or indeed the West Memphis Three, are wrongfully convicted and imprisoned for crimes they didn't do. That's one of James's many classes of true crime literature quarks and such here. He does a nice job of sorting, among other things, and I came away with a long list too. I enjoyed this a lot. Recommended for anyone with an interest in the stuff.

In case it's not at the library.

I thought James looked most silly (recognizing many others in baseball have seen him as silly and been wrong) attempting to elucidate the paradoxes of Lizzie Borden with a weird point system. I liked his theory of the JFK assassination, that the magic bullet was the accidental firing of a Secret Service gun, because why not? He seems worst to me on '60s crime more generally, veering toward Jack Webb territory with strained theories about liberals, hippies, and especially the Earl Warren Supreme Court. That theme became shrill for me and made me like or trust him less. On the other hand, we are broadly in agreement about the literature. Yes, it is full of ugly photos, bad writing, and human depravity. But it is actually about the most vital and profound issues: life, death, and judgment. Back of that, however, maddeningly, down in the nitty-gritty of the crimes and investigations, it starts to look like the bizarre subatomic world of physics, where forces are at work, but we don't understand them. That's what's so fascinating. We're not always even sure what happened. Thus, for example, the class of cases where people, such as Tim Masters in Fort Collins, Colorado, or indeed the West Memphis Three, are wrongfully convicted and imprisoned for crimes they didn't do. That's one of James's many classes of true crime literature quarks and such here. He does a nice job of sorting, among other things, and I came away with a long list too. I enjoyed this a lot. Recommended for anyone with an interest in the stuff.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, December 10, 2016

Eight Black Horses (1985)

At this point—have I said this before?—I have to admit my heart falls a little whenever I start a book in the 87th Precinct series of police procedurals by Ed McBain and find it's a Deaf Man story. It's a little like realizing a Star Trek episode is about Q, or Lwaxana Troi. The Deaf Man books are giant comic book capers filled with exaggerated and unlikely event, your basic Riddler v. Batman scenario. In this one, traveling under the name Dennis Döve (and asking people to call him "Den" because "den döve" means "the deaf man" in Swedish), he sends confusing messages to the 87th Precinct detectives: images of nightsticks, badges, hats, wanted posters, all things with a vague police theme. The first is of eight black horses. What could this nefarious villain be planning now? Thanks to the omniscient narrator, we see the Deaf Man bed one woman, kill another, tell his henchmen to do this and that, all but cackle and rub his hands. What in the world is he up to? You'll find out soon enough if you just keep reading the book. And it's probably the only way you'll figure it out. Technically, that makes this "unfair" mystery story writing. Eight Black Horses is not an outright failure, but it's not that good and it's way too busy. At this point in the series the novels are about twice the size of the earlier ones. A lot of the extra space goes to understanding the characters better. We learn here, for example, that the reprehensible Andy Parker was married at one time, and how it contributes to his chronic bitterness and rage, which makes him a bad cop. Little is heard from Meyer Meyer, and even Steve Carella is more of a sideline character. No, this one is all about the Deaf Man, which is awkward given the omniscient narrator coupled with the need to disclose some but not all of what he is doing. McBain has painted himself into an odd way of telling the story, not to mention that it's as unbelievable as ever with this character. Once the orchestrated mayhem begins, it's all flash and sizzle, like nothing that ever happens anywhere. I'm willing to indulge McBain these exercises because I'm trying to read them all anyway, and his storytelling works pretty well even when it's for something silly. So if you're reading them all like me, whatever. The rest of you can move it to the back of the stack. Unless you like the Deaf Man stories, in which case knock yourself out.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Friday, December 09, 2016

Ice (1983)

Here's a novel that's typical of the '80s for the 87th Precinct series of police procedurals by Ed McBain. Over 300 pages, with a single-word title whose metaphorical possibilities are worked over methodically (compare Tricks, the best of them). So it is set in February, involves cocaine, and also a theatrical-world scam known as "ice" (a term I'd never heard before, though I knew the scalping technique). There are also diamonds—you knew there were going to be diamonds—which are hidden inside ice-cube trays. Brrr. The killer is a cold motherfucker too, though I know many criminals in fiction are cold. As usual, except lately, it's a decent mystery story, keeps you guessing, and plays fair, for the most part. I've heard a new term going around: "rapey," which unfortunately often applies to McBain's work. A variation I haven't heard yet applies even more to him: "knifey." Ice is rapey and it is knifey too, though mostly (not always) they are off to the side, in the developing relationship between sad sack turned bad cop Bert Kling (just divorced from his model wife Augusta, who starred in Heat, set in August) and rape decoy specialist Eileen Burks. Ah ha—did the light just go on for you too? That's where all the rapey stuff goes in this one, and a lot of the knifey stuff too. And McBain is really treading risky territory here, attempting to make Eileen a hot sexy redheaded bombshell who has a complicated rape fantasy in her sexuality. Not in her police work, thank God. But I'm not really sure that makes it any better. It feels uncomfortably like McBain's complicated rape fantasy in a way that is annoying at best, or icky and worse. So that's unfortunate. All the personal development is basically with Kling and Eileen. Cotton Hawes and Andy Parker are absent. Meyer Meyer, Arthur Brown, and of course Steve Carella are present. Teddy makes a brief appearance. This one is big but it's mostly about the case, which is mostly about the metaphor conceit. I like setting it in February, as in many ways it's the cruelest month of the winter—still dark and bleak and cold, but now with phony make-believe holidays, Valentine's Day and Presidents' Day, neither one of which anybody ever knows where to put the apostrophes. McBain works those holidays pretty well here. There's a comical phony priest who reminds me a little of Samuel Jackson in Pulp Fiction. I realize I'm grasping at straws now. OK, it's not one of his best either.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Thursday, December 08, 2016

Heat (1981)

Heat is a decent entry in the 87th Precinct series of police procedurals by Ed McBain, though something of a sad one. The main case involves a locked-room type of apparent suicide. For the most part even that takes a backseat to the personal dramas with hapless Bert Kling, who suspects his wife Augusta is cheating on him, gets pretty hot about it, and sets out to catch her. There's also a psychopath trailing him, in order to settle a grudge. I'm not sure McBain is playing fair with this one either, as he is deliberately misleading on at least one important point. Even worse, the excesses Kling indulges in his pursuit of Augusta are unconscionable. He gets a search warrant under fraudulent conditions and uses it to harass and intimidate someone who is guilty of nothing except being unlikable. There are no repercussions from this, not here or in any subsequent novel. It's appalling—other detectives have to know, certainly our hero Steve Carella, but they appear to cover it up. Oh well, and never mind about the guy held at gunpoint in the middle of the night. Anyway, McBain is plainly more interested in this storyline than in the ostensible main case, which I'll call a good thing. I like that he goes in for the long-term character development, it's the main thing that merits any comparison to Balzac, even if I'm not convinced he always does such a good job of it. Bert Kling loses lots of points on the decent cop score here, and unfortunately McBain seems altogether too sanguine about it too. It's given more as a series of understandable and noble mistakes rather than criminal. Just so, the main case gets rote, turning on a lifelong fear of pills and a suicide death by barbiturate overdose, and the resolution is barely believable. The heat theme is handled all right—it's set in August, no surprise. A corpse is left to rot in a closed apartment with the air conditioning purposely turned off. Mostly I came away from this saddened by the behavior of Bert Kling and how it appears to be condoned.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Wednesday, December 07, 2016

Ghosts (1980)

Lately I haven't been having a lot of luck with the 87th Precinct series of police procedurals by Ed McBain (Evan Hunter, which wasn't his real name either). Here is yet another weak one. It's not even very interested in the crime in this case, let alone the police procedure for solving it. The main thing (after the usual unpleasant fixation on knives, which manifests as a description of all 19 wounds in a slashing and stabbing homicide) is the supernatural. The victim is the writer of a bestselling book about a haunted house in Massachusetts. I'm slow, so it took me awhile to notice the publication date and realize he must be riffing on Jay Anson and The Amityville Horror (the book which served as the pretext for the movie). That's McBain's other main interest here, horror writing and specifically the ghost story. Things happen that seem to be purely supernatural, including a medium with unexplainable powers. Interestingly (or not), she also looks exactly like Steve Carella's wife Teddy. And a Massachusetts winter storm strands Carella with her, as he is investigating a haunted house in a small town. Which also has some connection to Salem while we're at it. Oh it's piled on high here. And it's reasonably effective—weird, moody, vaguely unsettling maybe even. But what's this doing in the middle of my police procedural? It cheats in a really profound way on the whole premise of the series: rational investigation, scientific principles, all that. But what the hell, I suppose, why not? I remember saying something earlier about McBain's restless creativity. Still, it's annoying that the episode is equally as much about boy scout Steve Carella remaining true to his wife even in a situation where almost anyone could forgive him. The medium, recall, looks exactly like Teddy, which, as a plot point, only becomes more creepy the longer we have to live with it. What's more, this medium also has an identical twin sister who is a slut in all but name, so there you have it. Really, I'm not making this up. McBain did. Triple Teddy Strike Force. I guess it all comes with the territory, and to be fair, McBain has explored the bent toward horror elsewhere in the series (the "Nightshade" story in Hail, Hail, the Gang's All Here), though never so shamelessly, wantonly indulging the supernatural. I can't really speak to his career as Evan Hunter or other pseudonyms, but I wouldn't be surprised to find he's written a horror novel or two. I would then bet you knives figure prominently. Well, nobody's perfect. But Ghosts is an underperformer in the series by most standards.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Tuesday, December 06, 2016

He Who Hesitates (1964)

This is one of the more formalist experiments that show up in Ed McBain's 87th Precinct series of police procedurals. If it's not entirely pulled off, well, at least he was trying. That restless creativity is also something to like about him. The experiment is also probably the reason that it's very short—hard to sustain. What we have is the point of view of a temporary visitor to the city, Roger Broome, a craftsman in wooden goods such as salad bowls and utensils. He encounters five of the detectives, which is way too much coincidence, all things considered. From the beginning he has something on his mind, or his conscience, and he keeps intending to go to the police. But [the title]. For much of it we have no idea if he's committed a crime, or what, which is clarified later. It depends on many things that don't seem very likely to me. For example, that a woman would notice an abandoned refrigerator in the basement of an apartment building had been stolen. Then that the police would investigate to the extent of canvassing the building. There's a general nod in the direction of Alfred Hitchcock's Psycho, which makes sense for its time. It's also interesting to watch McBain telescope his detective caricatures to the barest terms: Hall Willis "the short one," Cotton Hawes (Broome hears it as "Horse"), with red hair and white streak, Meyer Meyer, bald, Steve Carella, with a beautiful deaf wife, radiating a sense of decency. (McBain always does favor Carella, doesn't he?) There's even a kind of sickening twist at the end. It probably made a good proposal pitch. It's fun to review the premise as now when I'm writing it up. But it never really transcends the bounds of its concept. What we appear to have in the end (spoiler alert) is a psychopath. As everyone knows, psychopaths are going to do what psychopaths do. It's literary license to do practically anything. That's one problem, though the sense of grim chill might arguably merit it. Mostly I missed the personalities of the 87th Precinct detectives, who played in the background, as they had to. Even at that, they were a little too loud and omnipresent. File this one under noble failed experiment, and don't even think about reading it first in the series. Really.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Monday, December 05, 2016

Ten Plus One (1963)

This entry in Ed McBain's 87th Precinct series is a single "big case" mystery with most of its essentials as if filched from an Agatha Christie cozy. It doesn't really play fair either way. As a cozy, it does not give us anything like a reasonable chance to figure it out. As a police procedural, it's just a little unbelievable. A sniper is on the loose in the 87th Precinct, which means our usual gang of detectives is responsible for the case, including all the murders that follow. There's also a Nancy Drew character on hand, Cindy Forrest, who later becomes a love interest for Bert Kling. At first the detectives think it's a serial killer—it's 1963 so the term wasn't yet common, making him a "nut" or a "madman." Working at the problem assiduously, the detectives finally find the link among the victims and counting, and then the tiresome business of playing out follows. This isn't one of the best, I must say. It's just the one case, which is rarely believable at any point, and the personal asides are minimal. At the same time it's a little longer than earlier volumes, so the result is it also feels padded, riding on the sensationalism of the Deadly Sniper. Minneapolis is mentioned, which might have some interest for anyone who's lived there, though the city itself is all off-stage. The year 1963 marks a low point in McBain's productivity on the series, along with 1962, which may or may not be explained by his working on movies such as Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds and Akira Kurosawa's High and Low. This one mostly feels like McBain is phoning it in. The resolution turns on an astonishing presumption of both depravity and prudery, removing it definitively from the cozy realm. Across the arc of the story, once the sniper gets to snipin', that's when it really goes off the rails. Which covers the broad majority of action here. You can hold off on this one awhile.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Sunday, December 04, 2016

Like Love (1962)

Here's another very short novel in the 87th Precinct series of police procedurals by Ed McBain), and another one that mostly resembles a conventional mystery story. A couple is found dead of apparent suicide in a tenement apartment. The gas for the oven was opened up and eventually the apartment exploded, smashing much of it to smithereens. It's typical exaggerated McBain violence. The dead couple is found in their underwear, lying in bed together, with a suicide note nearby. At this point, ineffable cop instinct sets in—it's Steve Carella as the main detective, as usual, with Cotton Hawes partnering with him on the case. Bert Kling and Meyer Meyer are also around to help out. As these things go it's a reasonably good puzzler. McBain was usually competent about devising these stories, inserting the red herrings, and finally explaining it all. That talent, in fact, is a critical element in the keeping the series going with the variety that it has. The mysteries can often carry the momentum, while he sorts out what he wants to do with the characters for the long term. There's also a separate suicide case, which occurs at the beginning and later impinges on the investigation of the dead couple. The title phrase is spoken two or three times along the way to inject notes of jaded cynicism, corrupted innocence, or a little of both. There's not much here on the personal side. Bert Kling is grieving the death of a girlfriend in an earlier book and that's about it. I wasn't much interested in the case—the whole thing seemed improbable to me, no matter what the "solution" turned out to be. So mostly I rode along on McBain's bantering voice. I wouldn't count this as one of the better books in the series, but as something for travel or a sleepless night it's perfectly adequate. It delivers an enigma and then, if you follow along far enough, a plausible resolution. Maybe you can get some sleep now. Maybe your plane is ready to land now.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Friday, December 02, 2016

Patty Hearst (1988)

UK / USA, 108 minutes

Director: Paul Schrader

Writers: Patricia Hearst, Alvin Moscow, Nicholas Kazan

Photography: Bojan Bazelli

Music: Scott Johnson

Editor: Michael R. Miller

Cast: Natasha Richardson, Ving Rhames, William Forsythe, Frances Fisher, Jodi Long, Peter Kowanko, Tom O'Rourke, Gerald Gordon

The Patty Hearst story is always going to be interesting, like the Jonbenet Ramsey murder, JFK assassination, and Lizzie Borden crimes, because of a continuing sense we still don't even know exactly what happened—that it might be impossible to know, it's so slathered over now with distortions of celebrity and passing time. The crusading prosecutor in director and cowriter Paul Schrader's formally fictional treatment of Patty Hearst puts it this way: "America wants to know. Did she or didn't she? Was she or wasn't she?" The scene is a conference between lawyers, late in the movie, after the fugitive Patty Hearst has been run to ground with the remaining members of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), a year and a half after the kidnapping.

F. Lee Bailey and his team, representing Hearst, cannot believe prosecutors are thinking of taking the case to trial, arguing it would be an open-and-shut case of coercion in a military setting. After Bailey realizes they are serious he makes the speech that defines the problem of Patty Hearst: "How are you gonna get a fair jury? In the '60s, every parent sent their nice normal kid off to college, and bingo! It was like the kid got kidnapped by the counterculture. Turned into a commie and said screw you to society and his parents. Lived in a commune and had free sex with Negroes and homosexuals. They think Patty did the same thing." To which the crusading prosecutor (Tom O'Rourke) responds: "Didn't she?"

Director: Paul Schrader

Writers: Patricia Hearst, Alvin Moscow, Nicholas Kazan

Photography: Bojan Bazelli

Music: Scott Johnson

Editor: Michael R. Miller

Cast: Natasha Richardson, Ving Rhames, William Forsythe, Frances Fisher, Jodi Long, Peter Kowanko, Tom O'Rourke, Gerald Gordon

The Patty Hearst story is always going to be interesting, like the Jonbenet Ramsey murder, JFK assassination, and Lizzie Borden crimes, because of a continuing sense we still don't even know exactly what happened—that it might be impossible to know, it's so slathered over now with distortions of celebrity and passing time. The crusading prosecutor in director and cowriter Paul Schrader's formally fictional treatment of Patty Hearst puts it this way: "America wants to know. Did she or didn't she? Was she or wasn't she?" The scene is a conference between lawyers, late in the movie, after the fugitive Patty Hearst has been run to ground with the remaining members of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), a year and a half after the kidnapping.

F. Lee Bailey and his team, representing Hearst, cannot believe prosecutors are thinking of taking the case to trial, arguing it would be an open-and-shut case of coercion in a military setting. After Bailey realizes they are serious he makes the speech that defines the problem of Patty Hearst: "How are you gonna get a fair jury? In the '60s, every parent sent their nice normal kid off to college, and bingo! It was like the kid got kidnapped by the counterculture. Turned into a commie and said screw you to society and his parents. Lived in a commune and had free sex with Negroes and homosexuals. They think Patty did the same thing." To which the crusading prosecutor (Tom O'Rourke) responds: "Didn't she?"

Wednesday, November 30, 2016

"The Lover of Horses" (1986)

Read story by Tess Gallagher online.

Tess Gallagher's story is less a narrative than a brooding meditation on death—well, on life too. The life and death belong primarily to the lover of horses of the title, the first-person narrator's great-grandfather, by reputation a horse "whisperer." But it's also about her father, related to her great-grandfather only by marriage. As she sees it, they share a similar experience, swept up by life, chosen by something outside of and greater than themselves. "[H]e was in all likelihood a man who had been stolen by a horse," she writes of her great-grandfather's abandonment of his family at the age of 52 to join a circus. Thus, she reasons, the impulse to make oneself an outsider was not just an influence but a positive factor in all their decisions. In the case of her father the lack of bloodlines might make it something of a stretch, but OK. Her father loved to play cards, or more accurately gamble. Near the end of his life, in his 70s, he finds a game and has an extraordinary run of luck. It is a high point of his life, and highly meaningful—or anyway that's how his daughter, the first-person narrator, sees it. On some level it's rationalizing, but the story seems to believe it and even manages to dignify it, like a good Joni Mitchell song. Gallagher was more a writer of poetry, and in many ways that's how this story feels. Everything is pointed toward an idea that, at least in some cases, things choose us and not the other way round, as we usually see them. Horses chose her great-grandfather, gambling chose her father, presumably writing, or maybe love for her father or family, has chosen this writer. I'm not sure there's much ambiguity here, except perhaps that grief has affected her, distorted her view, which seems unlikely. And I'm not sure there's much more to the story than that. It seems slight in some ways—the easy argument is that these men are failures. But the narrator wants us to look beyond that. For example, at the joy of her father finally encountering his long-sought streak of good luck. She wants us to see joy where we might be inclined to see obsession, or something similarly unhealthy. Maybe so, maybe so. But hard to say.

American Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks

Tess Gallagher's story is less a narrative than a brooding meditation on death—well, on life too. The life and death belong primarily to the lover of horses of the title, the first-person narrator's great-grandfather, by reputation a horse "whisperer." But it's also about her father, related to her great-grandfather only by marriage. As she sees it, they share a similar experience, swept up by life, chosen by something outside of and greater than themselves. "[H]e was in all likelihood a man who had been stolen by a horse," she writes of her great-grandfather's abandonment of his family at the age of 52 to join a circus. Thus, she reasons, the impulse to make oneself an outsider was not just an influence but a positive factor in all their decisions. In the case of her father the lack of bloodlines might make it something of a stretch, but OK. Her father loved to play cards, or more accurately gamble. Near the end of his life, in his 70s, he finds a game and has an extraordinary run of luck. It is a high point of his life, and highly meaningful—or anyway that's how his daughter, the first-person narrator, sees it. On some level it's rationalizing, but the story seems to believe it and even manages to dignify it, like a good Joni Mitchell song. Gallagher was more a writer of poetry, and in many ways that's how this story feels. Everything is pointed toward an idea that, at least in some cases, things choose us and not the other way round, as we usually see them. Horses chose her great-grandfather, gambling chose her father, presumably writing, or maybe love for her father or family, has chosen this writer. I'm not sure there's much ambiguity here, except perhaps that grief has affected her, distorted her view, which seems unlikely. And I'm not sure there's much more to the story than that. It seems slight in some ways—the easy argument is that these men are failures. But the narrator wants us to look beyond that. For example, at the joy of her father finally encountering his long-sought streak of good luck. She wants us to see joy where we might be inclined to see obsession, or something similarly unhealthy. Maybe so, maybe so. But hard to say.

American Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks

Tuesday, November 29, 2016

"A Romantic Weekend" (1988)

Story by Mary Gaitskill not available online.

This story comes from Mary Gaitskill's first collection, Bad Behavior, and it's more overt about the sexual kink she often writes about, BDSM, a complicated acronym you should look up for further tediously detailed discussion. Told third-person omniscient, "A Romantic Weekend" goes inside the heads of both its characters, an unnamed man who calls himself a sadist, and Beth, his mistress for the time being (he is married), who calls herself a masochist. Among other things, the story has a firm grip on the terrible foibles of these relationships, which come of projection, incoherence, and other poor interpersonal skills. "What do you want to do?" Beth asks the man during their all-night flight on the weekend trip in question. "I can't just come out and tell you," he says. "It would ruin it." And therein lies a primary rub of sexual relationships, not just BDSM. We want our partners to just know. Explaining things spoils it all. At the same time, the reports Gaitskill makes from inside the man's head point to what Beth finally realizes. He is a dangerous moron. He wants to beat her, torture her—he feels like an overprivileged 14-year-old. He doesn't appear to derive any pleasure, for the most part, and what he consciously seeks is closer to a porny fantasy of snuff: "With other women whom he had been with in similar situations, he had experienced a relaxing sense of emptiness within them that had made it easy for him to get inside them and, once there, smear himself all over their innermost territory until it was no longer theirs but his." This is a remarkable formulation of at least one projected mindset of the sadist, or top, or dom, but it's off. (All definitions are off a little in this realm.) The story seems to be straining after something much more dangerous as well, the mindset of a serial killer say, or at least sociopath. But this character's translation of it, perhaps exactly because of the malevolence, is also infantile and silly, closer to the kind of dominating that literally an infant would exert (see also: Donald Trump), which in turn is based on the humoring goodwill of its caretaker. You see how quickly it becomes so complicated. The man in this story is mostly unpleasant, particularly in his actions, and it's not long before he has completely alienated Beth. In fairness, Beth has some strange ideas herself about masochism (as do we all, ultimately, and the other way too). Neither one of these characters is very good at this. The story is not so much about BDSM but more about the treacheries of forging sexual relationships, the many places where compromise fatally undermines them. The problem of stating needs becomes an endless tiresome matter of negotiation, which ruins it. All the ways that sex comes up short, and love with it. It's not bad, but I think Gaitskill has done better elsewhere.

The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Short Stories, ed. Tobias Wolff

This story comes from Mary Gaitskill's first collection, Bad Behavior, and it's more overt about the sexual kink she often writes about, BDSM, a complicated acronym you should look up for further tediously detailed discussion. Told third-person omniscient, "A Romantic Weekend" goes inside the heads of both its characters, an unnamed man who calls himself a sadist, and Beth, his mistress for the time being (he is married), who calls herself a masochist. Among other things, the story has a firm grip on the terrible foibles of these relationships, which come of projection, incoherence, and other poor interpersonal skills. "What do you want to do?" Beth asks the man during their all-night flight on the weekend trip in question. "I can't just come out and tell you," he says. "It would ruin it." And therein lies a primary rub of sexual relationships, not just BDSM. We want our partners to just know. Explaining things spoils it all. At the same time, the reports Gaitskill makes from inside the man's head point to what Beth finally realizes. He is a dangerous moron. He wants to beat her, torture her—he feels like an overprivileged 14-year-old. He doesn't appear to derive any pleasure, for the most part, and what he consciously seeks is closer to a porny fantasy of snuff: "With other women whom he had been with in similar situations, he had experienced a relaxing sense of emptiness within them that had made it easy for him to get inside them and, once there, smear himself all over their innermost territory until it was no longer theirs but his." This is a remarkable formulation of at least one projected mindset of the sadist, or top, or dom, but it's off. (All definitions are off a little in this realm.) The story seems to be straining after something much more dangerous as well, the mindset of a serial killer say, or at least sociopath. But this character's translation of it, perhaps exactly because of the malevolence, is also infantile and silly, closer to the kind of dominating that literally an infant would exert (see also: Donald Trump), which in turn is based on the humoring goodwill of its caretaker. You see how quickly it becomes so complicated. The man in this story is mostly unpleasant, particularly in his actions, and it's not long before he has completely alienated Beth. In fairness, Beth has some strange ideas herself about masochism (as do we all, ultimately, and the other way too). Neither one of these characters is very good at this. The story is not so much about BDSM but more about the treacheries of forging sexual relationships, the many places where compromise fatally undermines them. The problem of stating needs becomes an endless tiresome matter of negotiation, which ruins it. All the ways that sex comes up short, and love with it. It's not bad, but I think Gaitskill has done better elsewhere.

The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Short Stories, ed. Tobias Wolff

Monday, November 28, 2016

"Rock Springs" (1982)

Read story by Richard Ford online.

Richard Ford's excellent and well-known short story is right out of the Raymond Carver school of damaged lives from the white underclass. It's told first-person by Earl Middleton of Kalispell, Montana, who has decided to move his family, such as it is—his daughter Cheryl, their dog Little Duke, and Edna, who is separated from a violent husband and has been with Earl for eight months. Earl happens to be looking at serious jail time for passing bad checks and needs to get out of the state. Though an edge of desperation is always in his voice, he tries to front an optimistic attitude. He steals a cranberry-colored Mercedes Benz from an ophthalmologist and plans (dreams) of a luxury ride all the way to Florida. But about 30 miles outside of Rock Springs, Wyoming, an engine warning light starts to show on the dashboard. The car is disabled even before they reach the town, and Earl has to come up with a Plan B. For the most part the story goes rollicking along as a kind of unusual road trip adventure. Edna and Cheryl are often bored, restless, and peevish. Yet there's a sense of inevitable ongoing collapse, even as Earl soldiers on. The fights between Earl and Cheryl are about old things. Those between Earl and Edna are about old things getting fitted to new partners. When Edna complains about how much danger they are in, Earl offers to buy her a bus ticket back to Kalispell. Later, when Edna tries to take him up on the offer, it's as if the floor (the flimsy floor) of Earl's life has vanished under his feet. He tries to keep it all elaborately upbeat, but he is seething with resentment, stung to his core. The ending is a wonderful model of ambiguity. Earl can't sleep, and leaves the motel room to prowl the parking lot, obviously thinking of stealing a car. But then what? Will he abandon his daughter, who is no older than 10? It seems likely. We realize at that moment that we really don't know Earl well. We know he is a criminal, without compunction, and we have seen how hard he works to keep himself on an even keel for the sake of others. We sense the furies underneath that—we sense that he is dangerous. But we have no idea where the lines and triggers are, what could happen. Along the way, the symbology is rich and strange: a terrible story of a monkey, a gold mine company town setting, and the desperate sweaty voice of Earl, with a great big have a good day smile on his puss. Chilling and pathetic at once, perhaps even reminiscent a little of Jim Thompson.

American Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks

The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Short Stories, ed. Tobias Wolff

Richard Ford's excellent and well-known short story is right out of the Raymond Carver school of damaged lives from the white underclass. It's told first-person by Earl Middleton of Kalispell, Montana, who has decided to move his family, such as it is—his daughter Cheryl, their dog Little Duke, and Edna, who is separated from a violent husband and has been with Earl for eight months. Earl happens to be looking at serious jail time for passing bad checks and needs to get out of the state. Though an edge of desperation is always in his voice, he tries to front an optimistic attitude. He steals a cranberry-colored Mercedes Benz from an ophthalmologist and plans (dreams) of a luxury ride all the way to Florida. But about 30 miles outside of Rock Springs, Wyoming, an engine warning light starts to show on the dashboard. The car is disabled even before they reach the town, and Earl has to come up with a Plan B. For the most part the story goes rollicking along as a kind of unusual road trip adventure. Edna and Cheryl are often bored, restless, and peevish. Yet there's a sense of inevitable ongoing collapse, even as Earl soldiers on. The fights between Earl and Cheryl are about old things. Those between Earl and Edna are about old things getting fitted to new partners. When Edna complains about how much danger they are in, Earl offers to buy her a bus ticket back to Kalispell. Later, when Edna tries to take him up on the offer, it's as if the floor (the flimsy floor) of Earl's life has vanished under his feet. He tries to keep it all elaborately upbeat, but he is seething with resentment, stung to his core. The ending is a wonderful model of ambiguity. Earl can't sleep, and leaves the motel room to prowl the parking lot, obviously thinking of stealing a car. But then what? Will he abandon his daughter, who is no older than 10? It seems likely. We realize at that moment that we really don't know Earl well. We know he is a criminal, without compunction, and we have seen how hard he works to keep himself on an even keel for the sake of others. We sense the furies underneath that—we sense that he is dangerous. But we have no idea where the lines and triggers are, what could happen. Along the way, the symbology is rich and strange: a terrible story of a monkey, a gold mine company town setting, and the desperate sweaty voice of Earl, with a great big have a good day smile on his puss. Chilling and pathetic at once, perhaps even reminiscent a little of Jim Thompson.

American Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks

The Vintage Book of Contemporary American Short Stories, ed. Tobias Wolff

The Edge of Seventeen (2016)

I was impressed with Hailee Steinfeld when she was not even 14 in the Coen brothers' remake of True Grit. She reared back and let the 19th-century dialogue fly like she'd been raised on a wagon train and a homestead, with iron in her spine. Haven't seen much of her since—she had a part in John Carney's Begin Again. Now it's more than five years later and she's still not even 21. And The Edge of Seventeen is depending on her for everything—it's basically a one-woman show, though with ample support. She plays Nadine, an introvert outcast in high school with a popular older brother, Darian (Blake Jenner). In all the world she has only one friend, Krista (Haley Lu Richardson), her best friend since 2nd grade, who wouldn't you know it ends up falling in bed and then falling in love with Darian. Insert sibling rivalry template. Also their father died in a terrible accident several years earlier during a Billy Joel song. Adolescence remains approximately the most narcissistic period in any person's life, and that's the steady refrain here, with a side of real calamities. Nadine's fits of pique grow old, I have to say, and so does her sad sack family (Kyra Sedgwick is their mother with barely a grip). Steinfeld spends a lot of time pouting and fuming. As usual with teen fare, the movie picks up when the soundtrack plays and/or during party scenes. But in the last third it turned out director and writer Kelly Fremon Craig actually has a pretty good grip on the storytelling, and slowly but surely the movie brought me around. Scenes of awkwardness were convincing, long and deeply awkward. Banter is deployed as a desperate attempt at being normal. It reminded me a little of Ghost World, which has a similarly disaffected teen lead who is also alienating herself from the people she needs most, and ultimately comes to learn her lesson. Nadine also learns the lessons she needs to learn in The Edge of Seventeen: accept people for who they are, give them a break, reach out for happiness once in a while, you know, the regular drill. And stop thinking about Donald Trump so much. She has a few potential love interests, appropriate and otherwise, including a grizzled Woody Harrelson as Mr. Bruner, a hip older teacher with a natural rapport, Nick Mossman (Alexander Calvert), a hot guy with a cool car (or is that the other way around?) who works at the pet store, and Erwin Kim (Hayden Szeto), who steals a couple of scenes as a cartoonist classmate even more introverted than Nadine. Szeto is one of the best parts. The story follows familiar beats of teen comedy and coming-of-age drama, and it ended up winning me over. Nice one.

Sunday, November 27, 2016

"Winter Dreams" (1922)

Read story by F. Scott Fitzgerald online.

F. Scott Fitzgerald published this story in 1922 and it's standard fare in many ways, more in the vein of his first novel, This Side of Paradise, though it is also considered a foundational story for The Great Gatsby. A young man from Minnesota—"Black Bear Lake," as opposed to the White Bear Lake which actually exists there—goes East for an Ivy League education, returns home, sets up in business, and eventually moves to New York City. Dexter Green is his name. Getting rich is his game. The woman he falls for, Judy Jones, is a kind of early pastiche of Daisy Buchanan and especially Jordan Baker, both in The Great Gatsby—beautiful, and careless. Dexter falls in love with her almost at first sight, when she is 11 and he is just a few years older. Not much happens beyond random lifelong encounters between them, though it is marked by Fitzgerald's gift for wonderfully extravagant language. Describing a summer evening scene by a lake, for example, he writes, "Then the moon held a finger to her lips and the lake became a clear pool, pale and quiet." Lines like that are one of the main reasons it's so difficult to make a movie of his work. He casts spells that only words can. Meanwhile, Dexter is busy getting rich and Judy is busy breaking hearts. That's what we do in a Fitzgerald story. It's also apparent from this story and the way it moves, again, why Fitzgerald had such a hard time accepting the realities of America and the world in the Great Depression '30s. He preferred the middle-class greed fantasies of the '20s, the "roaring" '20s, which he had a hand in inventing and mythologizing. So the people in this story golf and belong to country clubs, spend summers at lakes sailing, and in general extol the virtues of wealth (I use the word "virtues" ironically). Fitzgerald's characters are more or less innocents, these men falling in love with jaunty chicks. But it's a very white world and I'm not talking about the snow. It's a world scrubbed free of common troubles of the masses, a world of rank privilege. The justification, which he doesn't really even bother with, is "the human condition," people forever unsatisfied and into mischief. I'm prone to forgive Fitzgerald some because he could be such a peculiarly good writer. Even the names he comes up with are just wonderful: Dexter Green, who loves money, and first earned it as a golf caddy at the country club. Judy Jones (much later, Judy Simms). T.A. Hendrick. Mr. Hart and Mr. Sandoval (golfers). Krimslich (Dexter's mother's maiden name). Irene Scheerer (Dexter's fiancée). As for the title, it seems beside the point, in many ways. But I suppose it's an allusion to the ideal Fitzgerald had of the experience of growing up in the Midwest, dreaming to get money, a specific experience shared by Dexter Green and Jay Gatsby. For fans only.

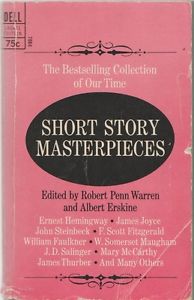

Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Robert Penn Warren and Albert Erskine

F. Scott Fitzgerald published this story in 1922 and it's standard fare in many ways, more in the vein of his first novel, This Side of Paradise, though it is also considered a foundational story for The Great Gatsby. A young man from Minnesota—"Black Bear Lake," as opposed to the White Bear Lake which actually exists there—goes East for an Ivy League education, returns home, sets up in business, and eventually moves to New York City. Dexter Green is his name. Getting rich is his game. The woman he falls for, Judy Jones, is a kind of early pastiche of Daisy Buchanan and especially Jordan Baker, both in The Great Gatsby—beautiful, and careless. Dexter falls in love with her almost at first sight, when she is 11 and he is just a few years older. Not much happens beyond random lifelong encounters between them, though it is marked by Fitzgerald's gift for wonderfully extravagant language. Describing a summer evening scene by a lake, for example, he writes, "Then the moon held a finger to her lips and the lake became a clear pool, pale and quiet." Lines like that are one of the main reasons it's so difficult to make a movie of his work. He casts spells that only words can. Meanwhile, Dexter is busy getting rich and Judy is busy breaking hearts. That's what we do in a Fitzgerald story. It's also apparent from this story and the way it moves, again, why Fitzgerald had such a hard time accepting the realities of America and the world in the Great Depression '30s. He preferred the middle-class greed fantasies of the '20s, the "roaring" '20s, which he had a hand in inventing and mythologizing. So the people in this story golf and belong to country clubs, spend summers at lakes sailing, and in general extol the virtues of wealth (I use the word "virtues" ironically). Fitzgerald's characters are more or less innocents, these men falling in love with jaunty chicks. But it's a very white world and I'm not talking about the snow. It's a world scrubbed free of common troubles of the masses, a world of rank privilege. The justification, which he doesn't really even bother with, is "the human condition," people forever unsatisfied and into mischief. I'm prone to forgive Fitzgerald some because he could be such a peculiarly good writer. Even the names he comes up with are just wonderful: Dexter Green, who loves money, and first earned it as a golf caddy at the country club. Judy Jones (much later, Judy Simms). T.A. Hendrick. Mr. Hart and Mr. Sandoval (golfers). Krimslich (Dexter's mother's maiden name). Irene Scheerer (Dexter's fiancée). As for the title, it seems beside the point, in many ways. But I suppose it's an allusion to the ideal Fitzgerald had of the experience of growing up in the Midwest, dreaming to get money, a specific experience shared by Dexter Green and Jay Gatsby. For fans only.

Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Robert Penn Warren and Albert Erskine

Saturday, November 26, 2016

"Barn Burning" (1939)

Read story by William Faulkner online.

This story sees William Faulkner in good form on the Snopes family. It's told third-person from the point of view of a young Snopes boy, who is ludicrously named Colonel Sartoris, though everyone calls him "Sarty." Sarty is only 10 or 11 years old, but he is regularly amazed and aghast at the behavior of his father, Abner. Abner Snopes is proud, filled with rage, and self-destructive. He perversely refuses to cooperate with anyone on anything, even friends or neighbors, even on things like building fences to enclose his animals. When these friends and neighbors object, and then impose penalties to counter his irresponsibility and offset the cost of their troubles, Abner gets mad and takes revenge, burning down their barns and such. Then the family has to move again. Abner Snopes is a classic Faulkner character—poor, white, ignorant, unyielding, and boiling with rage. Already Sarty can remember moving nearly a dozen times. Abner is described more than once as looking as if he were cut from tin, a familiar Faulkner formulation: " ... he could see his father against the stars but without face or depth—a shape black, flat, and bloodless as though cut from tin in the iron folds of the frockcoat." The story starts with a legal case against Snopes that can't be proved, but he and his family are run out of the area—once more Sarty has to move. At the new place, Abner immediately makes more trouble with his new landlord. The story is half shocking treachery and half pure comedy, as Abner alienates all people he suspects thinks they are better than him. In this case the victim is Major de Spain, also seen previously in Faulkner's work. The Snopes stories, in fact, are some of Faulkner's funniest, though the grim razor edges of violence and seething anger are never far. I'll also point out this story is a reasonably straightforward narrative. You always know what's going on and it has a lot of momentum. The ending, an epic confrontation between Abner and de Spain, is not entirely clear, but it's likely that's clarified elsewhere in the Faulkner canon. And if it's not, it's possible to make the note of ambiguity work too, so all good, right? The important part of the story to me is the unearthly unrelenting powerful physical presence of Abner. His anger can be felt palpably, yet even at his most threatening he is also an unmistakable comic element, a kind of downhome version of Tony Soprano, bumptiously cracking hilarious and maiming and murdering people. Remarkable balancing act and a good story.

Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Robert Penn Warren and Albert Erskine

This story sees William Faulkner in good form on the Snopes family. It's told third-person from the point of view of a young Snopes boy, who is ludicrously named Colonel Sartoris, though everyone calls him "Sarty." Sarty is only 10 or 11 years old, but he is regularly amazed and aghast at the behavior of his father, Abner. Abner Snopes is proud, filled with rage, and self-destructive. He perversely refuses to cooperate with anyone on anything, even friends or neighbors, even on things like building fences to enclose his animals. When these friends and neighbors object, and then impose penalties to counter his irresponsibility and offset the cost of their troubles, Abner gets mad and takes revenge, burning down their barns and such. Then the family has to move again. Abner Snopes is a classic Faulkner character—poor, white, ignorant, unyielding, and boiling with rage. Already Sarty can remember moving nearly a dozen times. Abner is described more than once as looking as if he were cut from tin, a familiar Faulkner formulation: " ... he could see his father against the stars but without face or depth—a shape black, flat, and bloodless as though cut from tin in the iron folds of the frockcoat." The story starts with a legal case against Snopes that can't be proved, but he and his family are run out of the area—once more Sarty has to move. At the new place, Abner immediately makes more trouble with his new landlord. The story is half shocking treachery and half pure comedy, as Abner alienates all people he suspects thinks they are better than him. In this case the victim is Major de Spain, also seen previously in Faulkner's work. The Snopes stories, in fact, are some of Faulkner's funniest, though the grim razor edges of violence and seething anger are never far. I'll also point out this story is a reasonably straightforward narrative. You always know what's going on and it has a lot of momentum. The ending, an epic confrontation between Abner and de Spain, is not entirely clear, but it's likely that's clarified elsewhere in the Faulkner canon. And if it's not, it's possible to make the note of ambiguity work too, so all good, right? The important part of the story to me is the unearthly unrelenting powerful physical presence of Abner. His anger can be felt palpably, yet even at his most threatening he is also an unmistakable comic element, a kind of downhome version of Tony Soprano, bumptiously cracking hilarious and maiming and murdering people. Remarkable balancing act and a good story.

Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Robert Penn Warren and Albert Erskine

Friday, November 25, 2016

"A Poetics for Bullies" (1964)

Story by Stanley Elkin not available online.

Stanley Elkin might appear to be 50 years or more ahead of our current preoccupations with bullying. But I'm not so sure. The first-person narrator is named Push, and he is a self-declared bully. He contrasts himself with bullies who beat up their victims, claiming they are more "athletes" than bullies. His style is mocking and tormenting through trickery, and he throws out a handful of his favorites at one point, most of which I happen to remember well from growing up, usually on the receiving end: making a match burn twice, the Gestapo joke, Adam and Eve and Pinch Me Hard. That's all good, and Push often reminded me uncomfortably of people I have known—even been. Then into this fiefdom one day comes a tall and patrician boy named John Williams, who is unafraid of Push. In turn, that makes Push a little afraid of him, or something. This is our central conflict, and I thought it was weak after how vividly Push had introduced himself. Williams is a world traveler, and probably rich. He has many fascinating stories to tell. All the kids love him, and his behavior helps to make them less afraid of Push. In turn, Push becomes even more intimidated by Williams. I didn't like this turn in the story—it turns it into a type of practical moral illustration. Push is a coward even though he denies it specifically early on, attacking the idea that all bullies are cowards. Yet in the end he is plainly a coward. I do agree with the cliché all bullies are cowards, but that's beside the point. I don't need to have it diagrammed for me. Besides, Push is more of a winning character than repulsive. He's charming, funny, well spoken. He's a bully but somehow that's forgivable. Maybe he doesn't seem so bad, or maybe it's the radiance of his self-awareness. Williams somehow has supernatural powers to intimidate Push, but we have to accept it as a given. We don't feel his powers much, though he does tell interesting stories and is somehow ingratiating. But that's not enough. From perfect self-awareness to almost no self-awareness is an unexplained sea change for Push in this short story. I don't believe it, and I don't think I understand the point. I like Push but I don't mind seeing a bully lose, so I think my stubborn loyalty to him suggests Elkin might be hedging his bets on making Push so bad. He's more like rapscallion, and that keeps him sympathetic enough, and that's what I don't get. Please don't tell me this is about bullies being redeemable. Next you'll be talking about racism against whites.

American Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks