Story by JT LeRoy not available online.

JT LeRoy, as we understood him at the time of the publication of this story, was a 20-year-old street hustler, drug addict, and vagrant. Later he turned out to be a 35-year-old woman named Laura Albert, who claimed the LeRoy persona enabled her to write things she couldn't have otherwise. This title story of the cycle of stories published under JT LeRoy's name in 2001 may not even fairly represent her, as the book is considered by some to be a novel (see also William Burroughs's Exterminator! or Denis Johnson's Jesus' Son). Actually, knowing what I know now, this story seems weak to me—mostly intended to shock and not very convincing. The violence feels exaggerated, for one thing, more like a scene from a Quentin Tarantino movie, arch and ironic and heavy-handed with the gore. I was hoping for more. It's possible I just can't get out of the way of the real-life context. Before the LeRoy persona was exposed, Albert had an enviable amount of support from figures such as Dennis Cooper, Mary Gaitskill, and Courtney Love, who are often markers of taste whatever you think of their own work. As literary hoaxes go, the LeRoy episode may be one of the best, that story itself possibly the best we ever get from Albert, who abandoned the LeRoy persona after she was exposed. Similar to the famous Stanley Milgrom experiment in terms of ethical behavior and results, it offered up profoundly interesting and uncomfortable insights. I can sit here and say I'm not much impressed with the story, which strains in obvious ways for grotesque effect. But how would I have felt if I'd been caught up in the hoopla before Albert was exposed? For what it's worth, I read the Da Capo Best Music Writing anthology she edited in 2005 as LeRoy shortly before the exposure and I thought and still think it's one of the best in the series, along with Gaitskill's the following year. So I'm sorry to say I suspect I might have liked this story more, or said I did, much as I'm inclined now to say I don't. Social pressures are clearly affecting judgment here, which remains the most interesting aspect of this story for me for now. Laura Albert fooled people by appealing directly to their own marginal interests in violence, drugs, and alternative sexuality. That makes it embarrassing more than anything for those fooled. Yet anyone, played correctly, is likely to be a victim. But again, what's most interesting to me for my purposes here are the judgments we make of the story. It's easy to be repulsed by it now, and find it shallow, but where is the line that separates it from the work of some of her victims? That's not an easy question.

The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things by JT LeRoy

Sunday, May 28, 2017

Saturday, May 27, 2017

Yes (2009)

For maybe 20 years now I've been in a kind of limbo with the Pet Shop Boys. I suspect most people still think of them as an '80s act, if not a one-hit wonder ("West End Girls," in spite of five more hits that followed in the US and many more internationally). I traveled deep into their catalog until approximately the 1996 album Bilingual, lingering very long and very hard on the Very Relentless package. I've always had a listen since then, even following the singles and B-sides and such (even that Battleship Potemkin thing), but little has ever insinuated itself again the way the work did of a golden period from 1987 to 1994. The closest I came was probably "The Night I Fell in Love," a brilliant shot across the bow to Eminem on the 2002 album Request, which I otherwise lost track of a week or two later. This pattern applied to Yes. When it came out I said Maybe and then the whole thing slipped my mind. So this is a story of one of those happy returns, a phenomenon I think I've seen with novels more than music. I try to read it, I try to read it, I try to read it—multiple attempts across years or even decades. Then one day I pick it up again and it's the best thing I've ever read. Yes is the best Pet Shop Boys album I've heard in a long time and just now I'm thinking the best of the 21st century.

This occurred to me a couple years ago, so the judgment has also turned out to be resilient. Is it really the upbeat positive note of the title? The music certainly pursues such avenues, albeit with their usual wryly detached irony. The opener, "Love etc." sets the tone, insisting you need love. The football chants on the chorus are relentless: "you need more you need more you need more you need more." I think they would find a way to make it say "sex" if that's what they meant. "All Over the World" follows on with a gorgeous takeoff that floats above the planet and marches into dignity accompanied by alien space gun sounds. It's beautiful and full of love etc.: "Exciting and new to say I want you." "Beautiful People," next, is not about the externality, though incapable of laying it on the "inner beauty" line. Still, that's what I hear in the chorus: "I want to live like beautiful people, give like beautiful people, with like beautiful people around." That sounds clannish and like Utopia at once. "Did You See Me Coming?" works because the arrogance of the title and play of the lyrics is belied by the ripening chest swoon of the melody, which somehow grows into a terribly sweet monster of sincerity. "Vulnerable" runs in place with the theme and may sound too much like a type of Pet Shop Boy song, i.e., product. Yet, for all that, the singer (as played, as usual, by Neil Tennant) is "so vulnerable," pleading his case. "More Than a Dream" might be long, but hits sweet spots of its own within the vibe. Even at their worst, the Pet Shop Boys are always at least as good as the pop Al Stewart, a firm floor for their entire career. "Building a Wall" is another song that may feel like reworking, but the twist on Brian Wilson's "In My Room" is fine: "not so much to keep you out, more to keep me in." Then "King of Rome" is more familiar territory ("My October Symphony," "To Speak Is a Sin," "The Samurai in Autumn"), but it's very beautiful territory. I could put down roots here—maybe I have. "Pandemonium" is a rave-up, standard issue, working to stoke the mood. If I'm really into it this is usually good for a minute or two of irresistible dancing with any cat handy.

The weakest songs follow, as if Pet Shop Boys Chris Lowe and Tennant were exhausted with the good times and/or already looking ahead. "The Way It Used to Be" and "Legacy" are the only songs here that pull some shades of self-pity around themselves, prefiguring Elysium. I still try to pay track sequencing some respects. At least there's the convenience that they're easily cut off when listening straight through. Otherwise, Yes tracks 1 to 9 are just the best thing going.

This occurred to me a couple years ago, so the judgment has also turned out to be resilient. Is it really the upbeat positive note of the title? The music certainly pursues such avenues, albeit with their usual wryly detached irony. The opener, "Love etc." sets the tone, insisting you need love. The football chants on the chorus are relentless: "you need more you need more you need more you need more." I think they would find a way to make it say "sex" if that's what they meant. "All Over the World" follows on with a gorgeous takeoff that floats above the planet and marches into dignity accompanied by alien space gun sounds. It's beautiful and full of love etc.: "Exciting and new to say I want you." "Beautiful People," next, is not about the externality, though incapable of laying it on the "inner beauty" line. Still, that's what I hear in the chorus: "I want to live like beautiful people, give like beautiful people, with like beautiful people around." That sounds clannish and like Utopia at once. "Did You See Me Coming?" works because the arrogance of the title and play of the lyrics is belied by the ripening chest swoon of the melody, which somehow grows into a terribly sweet monster of sincerity. "Vulnerable" runs in place with the theme and may sound too much like a type of Pet Shop Boy song, i.e., product. Yet, for all that, the singer (as played, as usual, by Neil Tennant) is "so vulnerable," pleading his case. "More Than a Dream" might be long, but hits sweet spots of its own within the vibe. Even at their worst, the Pet Shop Boys are always at least as good as the pop Al Stewart, a firm floor for their entire career. "Building a Wall" is another song that may feel like reworking, but the twist on Brian Wilson's "In My Room" is fine: "not so much to keep you out, more to keep me in." Then "King of Rome" is more familiar territory ("My October Symphony," "To Speak Is a Sin," "The Samurai in Autumn"), but it's very beautiful territory. I could put down roots here—maybe I have. "Pandemonium" is a rave-up, standard issue, working to stoke the mood. If I'm really into it this is usually good for a minute or two of irresistible dancing with any cat handy.

The weakest songs follow, as if Pet Shop Boys Chris Lowe and Tennant were exhausted with the good times and/or already looking ahead. "The Way It Used to Be" and "Legacy" are the only songs here that pull some shades of self-pity around themselves, prefiguring Elysium. I still try to pay track sequencing some respects. At least there's the convenience that they're easily cut off when listening straight through. Otherwise, Yes tracks 1 to 9 are just the best thing going.

Friday, May 26, 2017

Greed (1924)

USA, 129 / 239 minutes

Director: Erich von Stroheim

Writers: June Mathis, Erich von Stroheim, Frank Norris, Joseph Farnham

Photography: William H. Daniels, Ben F. Reynolds

Music: Robert Israel

Editors: Joseph Farnham, June Mathis, Glenn Morgan, Frank E. Hull, Rex Ingram, Erich von Stroheim, Grant Whytock

Cast: Gibson Gowland, Zasu Pitts, Jean Hersholt, Tempe Pigott, Dale Fuller, Chester Conklin, Sylvia Ashton

Life is short and the story of Greed is long—the original cut delivered by director, cowriter, and coeditor Erich von Stroheim was pretty long itself, on the order of seven to 10 hours. Accounts differ, but many agree it's one of the great lost masterpieces of cinema. Fifty years ago it was on the short list of the greatest films ever made, according to the Sight & Sound poll of 1962, after only Citizen Kane, L'Avventura (?!), and The Rules of the Game. In 1924, the studio figuratively thanked Stroheim for his work and assigned the recut to June Mathis, who got it down to a little more than two hours. I might have something close to that version—mine, from a Turner Classic Movies broadcast, is 129 minutes. On YouTube there is access to versions (usually on dubious pay sites) running 104 minutes, 90 minutes, 83 minutes, and 60 minutes—probably others too if you dig enough. I didn't bother with them. At Amazon, the best I could find available for purchase was a single used Region 2 DVD of a 129-minute version for $30.

Greed is thus truly a lost movie at this time, and more so than others in the category such as The Magnificent Ambersons or Metropolis. Indeed, by happy circumstance, Metropolis has been nearly entirely restored since just 2010. People keep hoping a complete version of Greed will turn up too but so far it hasn't. As it happens, I also have the reconstructed version put together by producer Rick Schmidlin in 1999 for TCM, using Stroheim's original shooting script, extant footage, and production stills. That version comes in just under four hours, which puts us closer to Stroheim's original but still well short. Greed has only the most modest commercial value now. It flopped even its time, not least because its story is a total bummer. Certainly it's one of the harder movies even to see from the top 100 films on the big list at They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?

Is it worth seeing? Oh geez, I knew you'd ask.

Director: Erich von Stroheim

Writers: June Mathis, Erich von Stroheim, Frank Norris, Joseph Farnham

Photography: William H. Daniels, Ben F. Reynolds

Music: Robert Israel

Editors: Joseph Farnham, June Mathis, Glenn Morgan, Frank E. Hull, Rex Ingram, Erich von Stroheim, Grant Whytock

Cast: Gibson Gowland, Zasu Pitts, Jean Hersholt, Tempe Pigott, Dale Fuller, Chester Conklin, Sylvia Ashton

Life is short and the story of Greed is long—the original cut delivered by director, cowriter, and coeditor Erich von Stroheim was pretty long itself, on the order of seven to 10 hours. Accounts differ, but many agree it's one of the great lost masterpieces of cinema. Fifty years ago it was on the short list of the greatest films ever made, according to the Sight & Sound poll of 1962, after only Citizen Kane, L'Avventura (?!), and The Rules of the Game. In 1924, the studio figuratively thanked Stroheim for his work and assigned the recut to June Mathis, who got it down to a little more than two hours. I might have something close to that version—mine, from a Turner Classic Movies broadcast, is 129 minutes. On YouTube there is access to versions (usually on dubious pay sites) running 104 minutes, 90 minutes, 83 minutes, and 60 minutes—probably others too if you dig enough. I didn't bother with them. At Amazon, the best I could find available for purchase was a single used Region 2 DVD of a 129-minute version for $30.

Greed is thus truly a lost movie at this time, and more so than others in the category such as The Magnificent Ambersons or Metropolis. Indeed, by happy circumstance, Metropolis has been nearly entirely restored since just 2010. People keep hoping a complete version of Greed will turn up too but so far it hasn't. As it happens, I also have the reconstructed version put together by producer Rick Schmidlin in 1999 for TCM, using Stroheim's original shooting script, extant footage, and production stills. That version comes in just under four hours, which puts us closer to Stroheim's original but still well short. Greed has only the most modest commercial value now. It flopped even its time, not least because its story is a total bummer. Certainly it's one of the harder movies even to see from the top 100 films on the big list at They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?

Is it worth seeing? Oh geez, I knew you'd ask.

Thursday, May 25, 2017

"Ile Forest" (1976)

Story by Ursula K. Le Guin not available online.

This story feels more like a fairy tale than a short story, let alone science fiction. The only thing "speculative" about it is the setting, an imaginary land in Central Europe. It's told essentially first-person, although there is a frame that introduces us to the narrator. He is a doctor, and he comes to a remote village with his sister to set himself up in practice. He notices a strange and beautiful mansion in a section of forest on his arrival, one of the features that makes him want to settle there. After the doctor and his sister have been there awhile, he is called to treat the master of the mansion. The master is close to death but, with the doctor's help, survives, and they become friends. The master lives by himself. He was married once but his wife ran away with another man, and now he prefers to live by himself. But—can you guess?—in short order the master and the doctor's sister have fallen in love and are thinking of marriage. But something about the master's story of simply accepting that his wife ran away doesn't sit right with either the doctor or his sister. Getting to the bottom of the man's mysterious past is the main thrust of this story, which proceeds serenely. It feels like a fairy tale, as I say, or at least much older than the 20th century. Part of that is the imaginary setting and the way the story moves. For example, a doctor traveling and living with his sister this way seems quaint, even eccentric, but also likely more normal in times past. Then there is all the careful narrative nesting. The master's story is recounted by the doctor many years after the events described. It's not the doctor's story at all nor even his sister's, but the master's. Multiple layers have to be pulled away to get at it. Yet it doesn't feel cute or overdone for effect in any way. At points it reminded me of Bram Stoker's Dracula, at points it reminded me of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. Yet there is little if anything that is supernatural or fantastic going on here. The master is left somewhat murky—I had the impression, when he was battling his illness, that he had to be an old man. Yet he is young enough or vigorous enough to attract a woman who is no older than her 30s at most. It feels in many ways like a straightforward romantic tale, yet there is something deeply disturbingly wrong about it too and I can't put my finger on exactly what that could be. A good one.

American Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks

This story feels more like a fairy tale than a short story, let alone science fiction. The only thing "speculative" about it is the setting, an imaginary land in Central Europe. It's told essentially first-person, although there is a frame that introduces us to the narrator. He is a doctor, and he comes to a remote village with his sister to set himself up in practice. He notices a strange and beautiful mansion in a section of forest on his arrival, one of the features that makes him want to settle there. After the doctor and his sister have been there awhile, he is called to treat the master of the mansion. The master is close to death but, with the doctor's help, survives, and they become friends. The master lives by himself. He was married once but his wife ran away with another man, and now he prefers to live by himself. But—can you guess?—in short order the master and the doctor's sister have fallen in love and are thinking of marriage. But something about the master's story of simply accepting that his wife ran away doesn't sit right with either the doctor or his sister. Getting to the bottom of the man's mysterious past is the main thrust of this story, which proceeds serenely. It feels like a fairy tale, as I say, or at least much older than the 20th century. Part of that is the imaginary setting and the way the story moves. For example, a doctor traveling and living with his sister this way seems quaint, even eccentric, but also likely more normal in times past. Then there is all the careful narrative nesting. The master's story is recounted by the doctor many years after the events described. It's not the doctor's story at all nor even his sister's, but the master's. Multiple layers have to be pulled away to get at it. Yet it doesn't feel cute or overdone for effect in any way. At points it reminded me of Bram Stoker's Dracula, at points it reminded me of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein. Yet there is little if anything that is supernatural or fantastic going on here. The master is left somewhat murky—I had the impression, when he was battling his illness, that he had to be an old man. Yet he is young enough or vigorous enough to attract a woman who is no older than her 30s at most. It feels in many ways like a straightforward romantic tale, yet there is something deeply disturbingly wrong about it too and I can't put my finger on exactly what that could be. A good one.

American Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Raymond Carver and Tom Jenks

Monday, May 22, 2017

Kong: Skull Island (2017)

The big ape with the soft heart is once again misunderstood in the latest King Kong chapter released earlier this year, when I was not in the mood for blockbusters. I overthought it, fretted, and put it off too long. But then one of my local multiplexes took mercy and brought it back for another week. (They also did me the favor of showing Colossal, speaking of monster movies, a decent specimen from last year with Anne Hathaway worth a look.) This King Kong story is set in 1973—it feels random, but soon enough is seen to suit the purposes of the screenplay, which among other things gives a shout-out to American military hubris and various corporate malfeasance. Samuel L. Jackson plays a disgruntled grunt who can't stand to lose. It clouds his judgment. Brie Larson (Room, The Spectacular Now, Trainwreck) gets the Fay Wray part, updated as an award-winning photojournalist who doesn't scream. Tom Hiddleston adds class to the joint with his ripped buff. And we're back on Skull Island, where it all started and where the bugs are big and the aborigines holy. John C. Reilly plays a soldier stranded there since World War II. But never mind all that. There's one reason we're here, and yes, those battle scenes are pretty good. It's that motherfucking big ape we love. Director Jordan Vogt (lots of TV), along with a team of six screenwriters, paces the action well. As with Peter Jackson's remake 12 years ago the yuck factor can roam high. There's just no good way to squish a big bug. And the Apocalypse Now vibe never quite makes sense, but the ordnance pyrotechnics are impressive. Me, I'm more a fan of the main event, King Kong taking on all comers in no holds barred wrestling to the death. Opponents include Rodan and Mothra types. You know them. There's some of the workmanlike grace of Willis O'Brien's (and later Ray Herryhausen's) stop-motion animation in this CGI somehow, especially in the big fight scenes. The woman I bought my ticket from asked if I'd seen it before and told me to be sure to stick around for all of the credits. Do you understand the commitment that requires for a movie with this degree of special effects and also a reasonably extensive '60s music soundtrack? They went on forever. Then there was a cryptic preview for a sequel. This movie's done pretty well at the box office. It hasn't made its money back yet but my multiplex did bring it back for a week. And it's King Kong, in the era of the franchise. Expect a sequel. Equal parts Jurassic Park and Lost.

Sunday, May 21, 2017

The Awkward Age (1899)

Henry James's whirl at writing plays earlier in the decade has full hold in this novel and the previous one, What Maisie Knew. Both are full of scenes, with dialogue and some stage direction but very little that helps us below the surface. It is all surfaces here, and James feels almost giddy with them. We are plunged into each scene with little to help us except what the characters say, and they are often hiding things from one another, or speaking subtly. It can be maddening—who and what are these people talking about? What are the things they say supposed to mean? These questions arise continually. Gradually a story is discerned, about a young woman, Nanda, who has reached the marrying age, and so must be married. She has two eligible suitors—one she loves but he cannot make a commitment and the other who loves her. Also there's a strange old guy hanging around who once loved Nanda's grandmother, detests her mother, and now has a thing for Nanda, though no one misses the age difference problem. Anyway, there are some clues for you. Good luck. As usual, I enjoyed reading it despite my confusions and misgivings. James's duty to his craft pays off well in many ways. Most surprising was how funny he can be, casually mocking certain figures of society. The title doesn't just refer to Nanda's post-adolescent time of life, you see, but also to the broader times in general, as the 19th century was turning into the 20th. Particularly some of the sideline women characters are funny in ways that sneak up on you. Their desperate ploys to maintain poise and dignity actually warranted giggling fits hours later as they floated back to mind. There is also something of the feel of a generational stamp to The Awkward Age—the "Fin de siècle" Generation, or some such. Van, the one who can't make a commitment, even when he loves, and Mitchy, the one who goes off and marries a harridan because Nanda told him she thought they'd make a good match, are lost soul frat brothers, comfortable in tails and keeping a bright face to the painful realities. At the finish the novel attempts to strike a note of pathos, which I think might be asking too much, given the generally wicked and gossipy narrative that holds sway. At the same time it's all wound up pretty well. I liked it on balance but you have to be prepared for a certain amount of confusion—"ambiguity" is the operating conceit, and James is often laying it on with a trowel. You're going to have to live with that to get through this. No doubt all the subtle dialogue accounts for the unusually high usage of "interlocutor" in this one.

"interlocutor" count = 25 / 402 pages (includes "interlocutress")

In case it's not at the library. (Library of America)

"interlocutor" count = 25 / 402 pages (includes "interlocutress")

In case it's not at the library. (Library of America)

Saturday, May 20, 2017

Money, Money, Money (2001)

With this late entry in the 87th Precinct series of police procedurals, Ed McBain was just about out of ideas and starting to run out of luck. There's little sense he's having much fun writing this. He doesn't even seem to like Steve Carella or care about any of the others. Carella's personal thread is something about his sister and mother both remarrying. He has issues. The story is a godawful mess involving counterfeit money, vicious Mexican drug lords, and terrorism. Here's where he's running out of luck. With Money, Money, Money, written between the November 2000 Cole bombing and 9/11 in 2001, McBain is caught looking like he can't imagine very big. In fact, the terrorists here verge on clownish stereotypes. Forty years earlier, in the first appearance of the Deaf Man (The Heckler), McBain imagined something more on the scale of 9/11. Money, Money, Money was written in the tail end of that historical period when radical Islamic terrorists were underestimated, shortly before we entered the period of overestimating them. Fat Ollie Weeks has another big role here. McBain obviously enjoyed working with him, but to me he's more often a bigot not redeemed by being smart. His eating is overstated and his pathetic pursuit of a creative hobby—piano playing, novel writing—is not that funny, sympathetic, or even believable. In general, Fat Ollie is not the comic relief McBain seems to think he is. McBain had lots of irons in the fire at the time, as Evan Hunter and otherwise, so I'll give him a break on a book I read so you don't have to. The cheapest available version now is the hardcover, and I was surprised to see how much "money, money, money" went into it on the original publication. The cover is green, like money, and the interior design riffs on a marking that's used to detect counterfeit $100 bills. So it appears McBain still had a respectable audience at the time. But it had to be faithful to the series by loyalty or habit.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Friday, May 19, 2017

The Big Bad City (1999)

One argument against reading the novels in the 87th Precinct series out of order might be that the later ones seem weaker read in isolation, the inconsistencies more nagging. I mean, here it is nearly the 21st century and Steve Carella, who was married in a 1959 novel, is worrying over his imminent 40th birthday. How does that work? It's possible after all this time that I'm just getting a little tired of McBain. But the characters in this one struck me as notably vacant. Nobody home, except the pro forma: Steve Carella loves his deaf wife Teddy, Hal Willis is short, and Meyer Meyer's father had a strange sense of humor. Cotton Hawes was so absent I thought he might have been knocked off in one of the books I haven't read yet. Matthew Hope, private detective star of a concurrent McBain series, shows up at one point. First time I've seen that. Apparently he and Carella came to be friends. The mystery story is a little better. It's 20 years after Calypso and McBain still hasn't figured out anything convincing about the worlds of rock music, let alone hip-hop. Here it's a nun who takes a year off from her vows to sing for a rock band, during which time she gets a boob job. Interesting array of facts for a nun. Then she goes back to her order. Then, a few years later, she is murdered in a park in the 87th Precinct. The Big Bad City might have the conclusion to the '90s thread about the murder of Carella's father, which I haven't found interesting yet. The enduring Fat Ollie Weeks has a prominent role here and as always is repulsive but entertaining but repulsive. Andy Parker's here too. There's some pointless time spent attempting to distinguish the bigotries of Fat Ollie and Parker. Since reading this one and going on to others, I've noticed how often McBain injects the term "the big bad city" into his narratives. It's one of his favorite phrases. Conveniently enough, simply reading that phrase has the virtue of covering most of the main points here.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Thursday, May 18, 2017

Romance (1995)

As late entries go in Ed McBain's 87th Precinct series of police procedurals, Romance is not bad. McBain manages to pull a few things together. It's just one case, involving an actress, and from there it gets a bit meta. A play called Romance is being produced, which is about an actress who is threatened and then murdered. Shortly before opening, the lead actress of the play reports she has been receiving threatening calls. Then she is stabbed, though not killed. Then she is stabbed and killed. It turns out she was involved in the first stabbing as part of a publicity stunt. Turning up dead is another matter. The plot is not that inspired but has its points. On the personal side, this is more of a Bert Kling episode, with Steve Carella working as his partner but well off to the side. The main point here is that Kling is starting a new relationship, this time with an African American woman, Sharyn (somehow pronounced differently from "Sharon"). She is a surgeon who directs forensics work for the Isola city police. McBain has certain things on his mind here: Rodney King, the 1992 Los Angeles riots, and race relations generally. Mostly it seems like a clumsy version of whitesplaining, but again, at least he's trying, and there are some interesting insights along the way. I like how he traces Kling's burgeoning racial sensitivities, as when Kling begins to notice how often white people mention that people are black, how extraneous and coded it almost always is. Kling also becomes more aware of racial compositions in public places and how they affect the way people behave. For her part, Sharyn is not sure about being involved with a white man—Kling is her first—and that's interesting too, though I don't much trust McBain speaking for her. Overall the mystery story in Romance is a little tired but the impulse to deal with race relations carries it. I'm not saying you won't wince.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Wednesday, May 17, 2017

Let's Hear It for the Deaf Man (1972)

Yes, it's true, it's another Deaf Man episode in the 87th Precinct series of police procedurals by Ed McBain. It might even be the most restrained one of all. But it's still a Deaf Man episode, so what you get is an elaborate bank robbery caper accompanied by a Batman and Riddler comic book story. Like all comic book villains (and only a few real-life ones, but I digress), the Deaf Man feels the need to inform police of his plans in cryptic ways, using their blunders to help pull off his capers. Or almost pull them off, as he never quite gets away with them, much like Mr. Mxyzptlk, from over at the Superman comic books, who is forever tricked into saying his ridiculous name backward again. Speaking of ridiculous names, this time the Deaf Man is traveling under the alias Taubman, which is kinda sorta German for "deaf man." O the wily Deaf Man! One of McBain's continuing strengths is constructing plots, so at least the bank robbery is a shrewd and interesting plan, though we are never privy to the whole thing until it goes down. This makes the climax more interesting, but also lends the foreshadowing an annoying air of peekaboo. But a mystery writer's gotta do what a mystery writer's gotta do. On the personal side, this is where Bert Kling meets his beautiful model girlfriend (then wife, then ex-wife) Augusta Blair. She comes along in the B story, which is actually the more interesting case, a series of burglaries in the precinct. The burglar is leaving behind kittens, because, get it? get it? he's a cat burglar. I said it was the most interesting storyline, not joke. Although, now that I think about it, it's just dumb enough to be true. And it has a better resolution than the Deaf Man story. But right, see title, this is a Deaf Man episode. The lame clues take up most of the time, but it's better than conducting full-scale war on the city as he has in earlier episodes, so count your blessings. The Deaf Man never pulls off his crimes (though he must be getting money from somewhere to finance them) yet he is never apprehended. It's another example of egregious police failure. This is basically skippable, unless you like the Deaf Man episodes, in which case go for it.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Tuesday, May 16, 2017

Jigsaw (1970)

I have the impression that Ed McBain (Evan Hunter, which was not his real name either) was one of those folks who takes pride in being "politically incorrect"—that is, offensive to certain sensitivities without really caring. I say this after reading a lot of his stuff and also because I have an uneasy feeling about the evolution of this entry in the 87th Precinct series. It's pure speculation, and you'll have to bear with me a bit. Jigsaw is one of the shortest novels in the series—I've got it at 175 pages—and focused on just one case. Six years earlier, a bank was knocked off to the tune of $750,000. The robbers were chased down and killed, but the money was never recovered. Now a photograph of where the money was hidden is surfacing. That photo was cut into eight pieces that are in the shape of jigsaw puzzle pieces (which had to be hell with the scissors, note). Those pieces were distributed to eight various parties who are now starting to turn up dead. A handy insurance investigator arrives to fill the detectives in on the details and even take a turn as a suspect. But this case, as happens now and then in the series, is weak mystery writing. It's less the point here, and feels like it's just going through the motions. What's really different is that the main detective is Arthur Brown, though Steve Carella is his partner on the case (Meyer Meyer and Cotton Hawes get a few lines too, working the case). Arthur Brown is McBain's superbad African American detective who rarely gets more attention than scenery, let alone the main role, which usually falls to Carella. In fact, this is actually Brown's only starring role in the whole series. And it is indeed a racialized narrative. My kindle version bizarrely has a copyright date of 1963, but this story is no earlier than 1967, and all other sources agree on 1970, which feels about right for the raised consciousness on display here. Brown is big like a boulder so people have to respect him. They constantly test him to see how far they can go, calling him a spade and such. A white woman throws herself at him for sex. Brown even gets to do a scene where he plays a corrupt Northern hustler to another white woman, this one from the South, who is so frightened she tells him everything he wants to know in minutes. All right, OK, different times, heart in the right place, etc. But then I started thinking about the tedium of this case, and I'm talking about tedium in a mere 175 pages, with this endless search for photo fragments. And then I started thinking about the title. Could it be? Yes, I'm afraid I think so. Here's how I've got it doped out. First came the idea to feature Arthur Brown in one of these novels. For the times, that would make it "relevant." Then came the title—McBain didn't know yet what he was going to do with it, but his daring politically incorrect instincts could not let go of it. Then he packed foofaraw around it: a photograph, a photograph cut into pieces in a ridiculous way, a photograph whose image is the only way to solve the crime. No way in hell has anything like this ever happened, not even in comic books.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Monday, May 15, 2017

Shotgun (1969)

Here's a theme title from the 87th Precinct series that finds a counterpart in a novel from a few years earlier, Ax. They're intended to shock with the brutality of the murdering class. Shotgun has an agenda that is clear from the start. "Detective Bert Kling went outside to throw up," goes the first line. He's at the scene where a couple has been slaughtered by two shotgun blasts apiece to the head. The queasy Kling is on the case with our usual hero, Steve Carella. Meyer Meyer and Cotton Hawes catch a separate case elsewhere, involving a middle-aged woman who has been killed with a knife to the heart. At this point, Ed McBain's id would like a word with us: "When somebody starts stabbing another person, there's a certain je ne sais quoi that takes over, a rhythm that's established, a compulsive need to plunge the blade again and again, so it shouldn't be a total loss. It is not uncommon in stabbings to find a corpse with anywhere from a dozen to a hundred wounds, that's the thing about stabbings." And that's the thing about McBain and knives in a very concentrated form, coming to full flower in these '60s novels. In another novel he has similar passages about the slicing effects of knives too. Maybe it's the right idea to save it all up for shock titles that are 100% shock. The only thing that surprises me is that the shotgun in this book is not sawed off—after all, circa 1969, Sam Peckinpah and all, you'd think it would be. The book is very short, well under 200 pages in mass market size, and as it happens the two cases come to interconnect. It's pro forma, as these mystery concoctions go. Again, this is about the violence and the weapons. There's very little about the personal lives of the detectives. The whole thing is just not very inspired. It exists primarily to shock, and sadly, by today's debauched standards, it can't even really do that. It's not such a blast after all.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Sunday, May 14, 2017

'Til Death (1959)

This lighthearted caper story comes out of one of the busiest years for the 87th Precinct series of police procedurals by Ed McBain. 'Til Death was the second of three novels in the series he published that year. I say it's lighthearted but actually the violence tends toward the brutal and over-the-top. It's the day of Steve Carella's sister's wedding. She is marrying Tommy Giordano, a neighborhood kid. He served with someone in the Korean War who now happens to be conducting an irrational vendetta against him. That's one thing going on. A jilted lover of Angela Carella has also got his mind on vengeance, and vengeance on his mind. And there are still more bad characters hanging around too. The wedding is ridiculously lavish, with giant ice sculptures, dozens of bottles of champagne, and a fireworks shoot to cap it off. Yeah, right. In a pig's eye. I doubt it! Also Steve Carella's wife Teddy is very pregnant and gives birth at the end of the novel. Busy, busy. You get the sense, as always, that McBain has a little fallen in love with the Carella family. He likes these people and wants to hang around with them, especially at such important times in their lives. But business is business, and action scenes are what move these units, and so we have pistol-whippers, sharpshooters, poisoners, and even someone sabotaging a car. And this is one of the short novels in the series. Carella enlists his detective buddies Cotton Hawes and Bert Kling so there are plenty of cops on hand for security. Meyer Meyer and Bob O'Brien are also there—we get more of a look at O'Brien than we usually do. Even Hal Willis gets a scene, back at the station house. At the wedding it's mostly mayhem and murder, with the cops unobtrusively conducting investigations, taking knocks to the head, getting hog-tied even, yet generally maintaining order until the wedding comes to a successful conclusion, and even a little beyond. This one has interest for the Carellas (and/or McBain's love affair with them). Much later in the series, in the '90s, the murder of Steve's father, who is featured here, becomes a significant continuing storyline. Part of it includes the divorce of Angela and Tommy. I suspect, if I knew the sales figures better, these would be bull years for the franchise and McBain had general license to do as he pleased to get three out a year. 'Til Death probably has very little interest as a stand-alone. It presumes all kinds of knowledge about backstory. At the same time, as these things go, this is the kind of story that makes the whole series more immersive. Proceed accordingly.

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Friday, May 12, 2017

A Man Escaped (1956)

Un condamné à mort s'est échappé ou Le vent souffle où il veut, France, 101 minutes

Director: Robert Bresson

Writers: Andre Devigny, Robert Bresson

Photography: Leonce-Henri Burel

Music: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Editor: Raymond Lamy

Models: Francois Leterrier, Charles Le Clainche, Maurice Beerblock, Roland Monod, Jacques Ertaud, Jean-Paul Delhumeau, Roger Treherne

Like Au Hasard Balthazar and Pickpocket, which precede A Man Escaped in the top 100 of the big list at They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?, director and screenwriter Robert Bresson's picture largely succeeds because it latches onto certain concrete circumstances. In the first two it's the life of a beast and the criminal art of pickpocketing, respectively, and in A Man Escaped it is the amazingly painstaking escape of a Frenchman from a German prison during World War II, based on true events. In fact, though I don't like it as much as the other two, in many ways A Man Escaped is the one that's most getting right down to the business of Bresson's major theme: the gyrations of the soul imprisoned in the flesh. That prison is perfectly externalized by the Montluc prison in Lyon, France, where the movie was shot and from which the original true-life escape was made.

As usual, some allowances must be made for changing times. The privations of the prison may look to us now more like a very bad dorm. Everyone's clothes are elaborately dirty but otherwise these prisoners don't look too much the worse for wear. Yes, we often hear shocking bursts of gunfire, suggesting executions (as most of the prisoners believe), or perhaps escape attempts cut down. But we actually see very little violence. The prisoners and guards seem mostly docile and without the air of aggression projected in modern prison scenes. Guards here are peevish and rude more than hostile, and inmates mostly just sullen. This is more of an existential imprisonment. It doesn't look like any kind of place I'd want to spend time, but it's preferable to the prisons we see in popular culture these days, where the preoccupation is rape, followed by random death by shiv. No one gives any thought to rape here, and the closest thing to a shiv is used only to help engineer the escape.

Director: Robert Bresson

Writers: Andre Devigny, Robert Bresson

Photography: Leonce-Henri Burel

Music: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

Editor: Raymond Lamy

Models: Francois Leterrier, Charles Le Clainche, Maurice Beerblock, Roland Monod, Jacques Ertaud, Jean-Paul Delhumeau, Roger Treherne

Like Au Hasard Balthazar and Pickpocket, which precede A Man Escaped in the top 100 of the big list at They Shoot Pictures, Don't They?, director and screenwriter Robert Bresson's picture largely succeeds because it latches onto certain concrete circumstances. In the first two it's the life of a beast and the criminal art of pickpocketing, respectively, and in A Man Escaped it is the amazingly painstaking escape of a Frenchman from a German prison during World War II, based on true events. In fact, though I don't like it as much as the other two, in many ways A Man Escaped is the one that's most getting right down to the business of Bresson's major theme: the gyrations of the soul imprisoned in the flesh. That prison is perfectly externalized by the Montluc prison in Lyon, France, where the movie was shot and from which the original true-life escape was made.

As usual, some allowances must be made for changing times. The privations of the prison may look to us now more like a very bad dorm. Everyone's clothes are elaborately dirty but otherwise these prisoners don't look too much the worse for wear. Yes, we often hear shocking bursts of gunfire, suggesting executions (as most of the prisoners believe), or perhaps escape attempts cut down. But we actually see very little violence. The prisoners and guards seem mostly docile and without the air of aggression projected in modern prison scenes. Guards here are peevish and rude more than hostile, and inmates mostly just sullen. This is more of an existential imprisonment. It doesn't look like any kind of place I'd want to spend time, but it's preferable to the prisons we see in popular culture these days, where the preoccupation is rape, followed by random death by shiv. No one gives any thought to rape here, and the closest thing to a shiv is used only to help engineer the escape.

Thursday, May 11, 2017

"The Horse Dealer's Daughter" (1922)

Read story by D.H. Lawrence online.

It's possible I was in the wrong mood for D.H. Lawrence, this story, or both, but its tedium was thick. The horse dealer's daughter—Mabel, by name—is an only daughter of 27, with two older brothers and one younger. Their mother died long ago, their father more recently. After his death the siblings ran his horse dealing business into the ground. The story takes place on the eve of their giving up the estate, having lost it. Now it's a matter of moving out. Mabel refuses to answer any of her brothers' questions about what she plans to do next. The second-oldest son, Fred Henry, is close friends with the village doctor, Jack Fergusson, who comes by to say goodbye. Fred Henry's and Fergusson's goodbye is so tender I caught myself wondering if they were gay, which is doubtful. I don't think it's consciously intended that way. Mabel is bereft by all these turns of event, starting even many years before with the death of her mother. She visits the cemetery and lovingly tends her mother's grave. All this takes place on the same day. Fergusson sees her at the cemetery, and she notices him too. Later, Mabel tries to drown herself in a pond. Fergusson sees what she's doing and comes to her rescue, nearly drowning himself in the process, as he can't swim. She is unconscious when he gets her out of the water. He takes her to her place, undresses and dries and treats her, with his clothes still full of the muck and stink of the pond water. She awakes. They have a conversation. Suddenly they are consumed by passions for one another, declare their love, and plan to be married in a day or two. It's the kind of fictional passage that really has to be carried by the language, or at least set up better. To me, last night, Lawrence failed on both. I think his language is rarely up to his scenarios, certainly not here, with stultifying descriptive details and too many murky points about their intense emotional states. Obviously it's about passion, to practically a demented degree, but it also seemed evasive about the sources. It could have been the overwhelming circumstances of an extraordinary day for either or both. It could have been Fergusson getting a good look at Mabel's body while he was caring for it. It could have been feelings Fergusson had for Fred Henry jumping siblings to Mabel. It could have been anything. Now they're getting married. It goes from screamingly dull to weirdly repulsive just like that. I'm sure it's not intended any such way. But it hasn't aged well, at least not for me.

Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Robert Penn Warren and Albert Erskine

It's possible I was in the wrong mood for D.H. Lawrence, this story, or both, but its tedium was thick. The horse dealer's daughter—Mabel, by name—is an only daughter of 27, with two older brothers and one younger. Their mother died long ago, their father more recently. After his death the siblings ran his horse dealing business into the ground. The story takes place on the eve of their giving up the estate, having lost it. Now it's a matter of moving out. Mabel refuses to answer any of her brothers' questions about what she plans to do next. The second-oldest son, Fred Henry, is close friends with the village doctor, Jack Fergusson, who comes by to say goodbye. Fred Henry's and Fergusson's goodbye is so tender I caught myself wondering if they were gay, which is doubtful. I don't think it's consciously intended that way. Mabel is bereft by all these turns of event, starting even many years before with the death of her mother. She visits the cemetery and lovingly tends her mother's grave. All this takes place on the same day. Fergusson sees her at the cemetery, and she notices him too. Later, Mabel tries to drown herself in a pond. Fergusson sees what she's doing and comes to her rescue, nearly drowning himself in the process, as he can't swim. She is unconscious when he gets her out of the water. He takes her to her place, undresses and dries and treats her, with his clothes still full of the muck and stink of the pond water. She awakes. They have a conversation. Suddenly they are consumed by passions for one another, declare their love, and plan to be married in a day or two. It's the kind of fictional passage that really has to be carried by the language, or at least set up better. To me, last night, Lawrence failed on both. I think his language is rarely up to his scenarios, certainly not here, with stultifying descriptive details and too many murky points about their intense emotional states. Obviously it's about passion, to practically a demented degree, but it also seemed evasive about the sources. It could have been the overwhelming circumstances of an extraordinary day for either or both. It could have been Fergusson getting a good look at Mabel's body while he was caring for it. It could have been feelings Fergusson had for Fred Henry jumping siblings to Mabel. It could have been anything. Now they're getting married. It goes from screamingly dull to weirdly repulsive just like that. I'm sure it's not intended any such way. But it hasn't aged well, at least not for me.

Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Robert Penn Warren and Albert Erskine

Monday, May 08, 2017

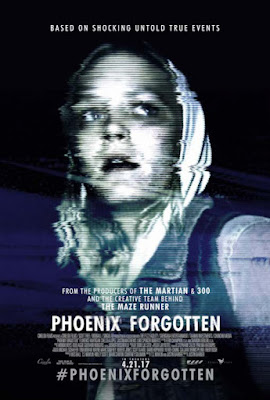

Phoenix Forgotten (2017)

The only true event in Phoenix Forgotten is the UFO incident in March 1997, when unexplained lights were seen over Phoenix by thousands of people and caught on amateur video. Everything else about this movie falls all too easily into the found-footage genre of which so many of us are getting so tired. But Phoenix Forgotten switches up the usual drill a few ways, and overall I thought it was intriguing and a pretty good time. Three teens investigating those lights go missing later in 1997. Our job, and the community's, is to find out what happened. Typically enough, the first half is the best part, taking the form of a Disappeared episode, the true-crime TV show that examined open missing persons cases. Phoenix Forgotten moves its story along briskly with news footage, talking heads interviews, and work in progress on a documentary about the case. The three missing teens, two boys and a girl, left their car parked neatly at the side of the road out in the desert. Like a good episode of Disappeared, it's almost perfectly mysterious. There were no useful clues at the car, which had been locked and was functional. Systematic searches went on for weeks but nothing useful was found. For the parents, it consumed their lives. The documentary filmmaker in the movie and our hero, Sophie Bishop, is the younger sister of one of the missing boys. It's 20 years later and she's consumed with it too. The dead end and key sticking point in the case is that a camera was left behind in the car. It was not like Sophie's brother to go anywhere without a camera, usually running—he was one of those, with the thing perpetually attached to his face. Eventually, through the use of plot devices, a second camera turns up. The tape has survived and on that tape we witness their fate. In fairness to director and cowriter Justin Barber, on his first feature, he doesn't make us wait long to see the tape once its existence comes along. He shows all of it, and it's a reasonable payoff. It's unfortunately too reminiscent of The Blair Witch Project, notably with scenes of vertiginous running, but it's not bad. In the hurly-burly of the finish we see lots of things that register later, images and unexpected behavior and so forth, to make it effectively unnerving beyond seeing it. Whatever those lights are—it seems likely it's aliens from outer space, though secret government projects are not entirely ruled out—they mean those kids no good. This is more the lame side of the movie, but good enough generally to carry the momentum home for an 87-minute ride. Phoenix Forgotten dips into the usual problems of these things, notably the ridiculous constant shooting no matter what is going on. No one could be that dedicated in some of these scenes. Yet found-footage films do have the advantage of capturing an immediacy and raw tension that conventional narrative movies rarely get to, which also helps explain why so many are horror pictures. That trade-off is my explanation anyway for why I seem to see so many and often end up liking them, with caveats. Other good ones: Cloverfield (the first), Paranormal Activity, [REC], and Trollhunter. And Phoenix Forgotten.

Sunday, May 07, 2017

Ship Fever (1996)

I'm not sure I've read many stories quite like Andrea Barrett's in this collection. They're grounded in 19th-century scientific currents, influenced directly by ongoing research and developments. They are always engaging and often moving. Gregor Mendel makes an abstracted appearance in the first story, for example, "The Behavior of the Hawkweeds," which wraps details of the friar scientist's biography into the story of a proud Czech woman whose grandfather was mentored by him during years of Mendel's obscurity, when he was fruitlessly studying bees and hawkweeds. In fact, a whole family drama is indirectly told, using techniques we understand better from late 20th-century fiction. The Czech woman's grandfather is accused of murder in an accidental death that ultimately destroys his life. All the stories in this collection, a National Book Award winner for fiction in 1996, have an economy and clarity of language that's a pleasure. The title story is nearly a hundred pages, involving the historical event of the typhus epidemic of 1847 at Grosse Isle, Canada, which stemmed from a huge ongoing emigration from Ireland. The immigrants arrived on ships with appalling conditions. Barrett paints a vivid picture of the dead and sick who travel in the holds of ship after arriving ship. She also documents the prejudice in Canada and the US militating against Irish immigrants. Into this intricately (and horrifically) imagined setting, Barrett inserts a story that much fits its Bronte sisters time frame. A man, a doctor, has been in love with a woman since they were both young children. But now she is married to another, and they have remained friends. The agony of his unrequited love is the next best thing to exquisite. He's off to battle the plague. I like the Victorian flavor of the romance—Canada was more or less officially Victorian at the time, I believe, and focusing on plague in the New World just adds even more layers. And there's still more here, stories full of science, and research, and historical context, alongside efficient heartrending tales. Or at least affecting. But come on, this has to be some kind of genre unto itself, yes? What's it called—historical fiction? History-of-science fiction? Industrial?

In case it's not at the library.

In case it's not at the library.

Saturday, May 06, 2017

Channel Orange (2012)

On and off for a few years now Frank Ocean's first album (which followed on the 2011 mixtape Nostalgia, Ultra) has been a pretty reliable staple around my place, especially in shuffle where its strongest songs do what listening to music is supposed to do, even with Ocean's characteristic tossed-off air: call attention to itself, build on the experience of hearing it, and erase time. My favorites include "Sierra Leone," "Super Rich Kids," "Lost," "Crack Rock," "Forrest Gump," and I'm sure I'm missing a few more, it's that kind of generous album. Though sloppy at their edges, the distracting word play and especially the melodies of these songs are often their own reward. You don't always get both together. "Crack Rock" insinuates with its mournful air and stubborn persistence but decrying the drug use the way it does is so clichéd I keep thinking it must be a put-on. Scanning down the track list, you will note there are three or four tracks around a minute or less, suggesting the dread indulgence of skits (a holdover of CD technology obviated by shuffle, compare lock-grooves with vinyl). But they're painless, two of them over in the first three tracks, bracketing the hit. Channel Orange starts on "Start," a 45-second sound abstraction with familiar downloading and computer sounds, then goes into the #32 "Thinkin' 'Bout You," and then the 39-second "Fertilizer," which is closer to a song fragment. From then on it's a solid set of quirky songs, with flashes of utter brilliance and moving displays of emotion, occasionally sustained. The lengthy "Pyramids" is an example of his perversities. It runs to nearly 10 minutes, starting with a stately march that seems to take place in ancient Egypt and gradually morphing into strip club scenes in the modern world. Love as usual escapes the singer and the sadness is infinitely sweet on the chorus. "Super Rich Kids" is one of the more sustained tracks, with a languorous pace and sultry grace. "The maids come around too much, parents ain't around enough"—the unbearable pain of fake friends, abandonment, and all the creature comforts. Channel Orange ends on the two-minute "End," which maybe picks up where "Start" finished even as it seems intended to loop back again? You tell me. I love parts of these songs madly—usually the chorus. And if the rest veers between self-indulgence and brainy ingenuity it's no less entertaining for that. Like I said, good for shuffle.

Friday, May 05, 2017

Clouds of Sils Maria (2014)

France / Germany / Switzerland, 124 minutes

Director/writer: Olivier Assayas

Photography: Yorick Le Saux

Editor: Marion Monnier

Cast: Juliet Binoche, Kristen Stewart, Chloe Grace Moretz, Brady Corbet, Johnny Flynn, Angela Winkler, Hanns Zischler

Many takes on Clouds of Sils Maria tend to focus on it as a backstage drama in the vein of All About Eve, but that's not exactly right. It's true there's a rivalry between a veteran performer, Maria Enders (Juliette Binoche), and a younger performer vying for her place, Jo-Ann Ellis (Chloe Grace Moretz). But until the epilogue that is mostly relegated to the level of an ongoing subplot in the background. The real conflict in this picture is between Maria and her personal assistant Val (Kristen Stewart) though it's perhaps less apparent why this conflict is central.

In many ways it doesn't matter because director and writer Olivier Assayas is so accomplished at directing and misdirecting our areas of focus, with a swooning love for motion and static gorgeous images that feel almost second nature at this point. Ultimately, Clouds of Sils Maria may be as shapeless and indeterminate as the metaphorical meteorological phenomena it's named for, that it climaxes on, and that it returns to again and again like touching base of some kind. It's set in the Alps of Switzerland—listen closely enough and you might hear Julie Andrews faintly warbling on the other side of that ridge. Hiking is a daily routine and getting lost can happen too.

Director/writer: Olivier Assayas

Photography: Yorick Le Saux

Editor: Marion Monnier

Cast: Juliet Binoche, Kristen Stewart, Chloe Grace Moretz, Brady Corbet, Johnny Flynn, Angela Winkler, Hanns Zischler

Many takes on Clouds of Sils Maria tend to focus on it as a backstage drama in the vein of All About Eve, but that's not exactly right. It's true there's a rivalry between a veteran performer, Maria Enders (Juliette Binoche), and a younger performer vying for her place, Jo-Ann Ellis (Chloe Grace Moretz). But until the epilogue that is mostly relegated to the level of an ongoing subplot in the background. The real conflict in this picture is between Maria and her personal assistant Val (Kristen Stewart) though it's perhaps less apparent why this conflict is central.

In many ways it doesn't matter because director and writer Olivier Assayas is so accomplished at directing and misdirecting our areas of focus, with a swooning love for motion and static gorgeous images that feel almost second nature at this point. Ultimately, Clouds of Sils Maria may be as shapeless and indeterminate as the metaphorical meteorological phenomena it's named for, that it climaxes on, and that it returns to again and again like touching base of some kind. It's set in the Alps of Switzerland—listen closely enough and you might hear Julie Andrews faintly warbling on the other side of that ridge. Hiking is a daily routine and getting lost can happen too.

Thursday, May 04, 2017

"Liberty Hall" (1929)

Read story by Ring Lardner online.

Ring Lardner is a writer I should probably read more. So is S.J. Perelman. But I digress. I happened to be rereading The Catcher in the Rye recently, where Holden Caulfield has high praise for Lardner, who died of tuberculosis at the age of 48. "Liberty Hall" is set in 1920s Manhattan (so it's not hard to see where Holden Caulfield might be coming from). The story is charming, witty, just really well done, and not shallow either, though it easily could have been. It's told in the first person by the wife of the main character, Ben Drake, who is a celebrated Manhattan composer—George Gershwin is name-checked as a "rival." Cole Porter and Hoagy Carmichael seem likely as more rivals, perhaps even models for Drake. Drake is plunged happily into his work and has little patience for glad-handing and swimming the social currents. Getting him out of exhausting social calls is the chief preoccupation here. People want to befriend him for the cachet of doing so, and they also want to feel superior to him. I understand this is a common problem of celebrity. The impossibility of it all climaxes when they meet the Thayers, a couple who seem much less than ordinarily grasping. Eventually the Drakes trust them enough to accept an invitation to stay with them as house guests for a week or two, for purposes of isolating and recharging, between jobs in Drake's busy life. But the Thayers quickly show they are the most grasping and controlling of them all, in scenes that are at once funny and painful. It reminded me very much, and in all good ways, of an episode of I Love Lucy. One such incident raises questions about when the story was written. Drake sees a copy of The Great Gatsby and eagerly picks it up, saying he had meant to get to it and is now grateful to find the opportunity. "'Heavens!' said Mrs. Thayer as she took it away from him. 'That's old! You'll find the newest ones on the table.'" The alert reader will have noticed she takes the book away from him, even as she piles on with the debt of her hospitality and her superiority (she has all the latest books, you see, whereas Drake has not even read the old Fitzgerald). That's how the story proceeds. It's exasperating chamber encounters and often very funny. As for the niggling issue of the date, I keep seeing either 1924 or 1929, or both, on the copyrights, which suggests to me it was published and then rewritten later for republication. The Great Gatsby, of course, was published in April 1925. At any rate, "Liberty Hall" is a good story—above all, funny, which is about the hardest thing to do in writing, but making heavy points about the (comical) human condition as well.

Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Robert Penn Warren and Albert Erskine

Ring Lardner is a writer I should probably read more. So is S.J. Perelman. But I digress. I happened to be rereading The Catcher in the Rye recently, where Holden Caulfield has high praise for Lardner, who died of tuberculosis at the age of 48. "Liberty Hall" is set in 1920s Manhattan (so it's not hard to see where Holden Caulfield might be coming from). The story is charming, witty, just really well done, and not shallow either, though it easily could have been. It's told in the first person by the wife of the main character, Ben Drake, who is a celebrated Manhattan composer—George Gershwin is name-checked as a "rival." Cole Porter and Hoagy Carmichael seem likely as more rivals, perhaps even models for Drake. Drake is plunged happily into his work and has little patience for glad-handing and swimming the social currents. Getting him out of exhausting social calls is the chief preoccupation here. People want to befriend him for the cachet of doing so, and they also want to feel superior to him. I understand this is a common problem of celebrity. The impossibility of it all climaxes when they meet the Thayers, a couple who seem much less than ordinarily grasping. Eventually the Drakes trust them enough to accept an invitation to stay with them as house guests for a week or two, for purposes of isolating and recharging, between jobs in Drake's busy life. But the Thayers quickly show they are the most grasping and controlling of them all, in scenes that are at once funny and painful. It reminded me very much, and in all good ways, of an episode of I Love Lucy. One such incident raises questions about when the story was written. Drake sees a copy of The Great Gatsby and eagerly picks it up, saying he had meant to get to it and is now grateful to find the opportunity. "'Heavens!' said Mrs. Thayer as she took it away from him. 'That's old! You'll find the newest ones on the table.'" The alert reader will have noticed she takes the book away from him, even as she piles on with the debt of her hospitality and her superiority (she has all the latest books, you see, whereas Drake has not even read the old Fitzgerald). That's how the story proceeds. It's exasperating chamber encounters and often very funny. As for the niggling issue of the date, I keep seeing either 1924 or 1929, or both, on the copyrights, which suggests to me it was published and then rewritten later for republication. The Great Gatsby, of course, was published in April 1925. At any rate, "Liberty Hall" is a good story—above all, funny, which is about the hardest thing to do in writing, but making heavy points about the (comical) human condition as well.

Short Story Masterpieces, ed. Robert Penn Warren and Albert Erskine

Wednesday, May 03, 2017

Just Kids (2010)

(requested by reader B.R.)

I came to it late, but really loved Patti Smith's memoir. I learned about a lot of things I hadn't known before: her mysterious first child, a soul-bonding friendship with the great photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, and all her fascinating adventures in New York in the late '60s and early '70s. It's an homage to her friend Robert more than anything, and often very tender. Smith remains a unique figure, a hippie chick with a punk attack, forever in love with poetry and words and art, and a Jersey girl under all of it. These themes are fleshed out more than ever here. She revered Rimbaud and Baudelaire, yet she also had shrewd instincts that served her well. She worked at Scribner's and later the Strand as a bookstore clerk for many years, and learned how to suss out good buys in collectors' editions. A move out of the Chelsea Hotel, where she and Robert lived for a year or two, and into a large studio space nearby, was financed by a 26-volume Henry James edition she found for cheap somewhere. Speaking of the Chelsea Hotel, that's the longest section in the book, with lots of interesting characters and obviously the period she remembers with the most fondness. She met Janis Joplin and William Burroughs there. She met Allen Ginsberg in an automat restaurant, where she was a dime short for what she wanted and he thought she was a boy he might be able to pick up. She had a kind of charmed existence for all its tribulations and difficulties then. Just Kids is perhaps most interesting of all for its story of the parallel developments of Smith and Mapplethorpe as artists. When they first met, thrown together two times by chance, he never intended to be a photographer and she never intended to be a rock star. They came to their places through one another, and not without their pains, because honestly, look how unlikely on the face of it that those two would end up together, given how far apart they went. Yet the bond was always there and always honored—that's the only thing to come away from this book with, and really it's a lot. It's the reason the book was written. It's very generous and in all the familiar ways Patti Smith is generous: acting the Earth Mother and the Holy Fool in the name of rock 'n' roll and art and poetry. It's a beautiful thing truly, and so is this book.

In case it's not at the library.

I came to it late, but really loved Patti Smith's memoir. I learned about a lot of things I hadn't known before: her mysterious first child, a soul-bonding friendship with the great photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, and all her fascinating adventures in New York in the late '60s and early '70s. It's an homage to her friend Robert more than anything, and often very tender. Smith remains a unique figure, a hippie chick with a punk attack, forever in love with poetry and words and art, and a Jersey girl under all of it. These themes are fleshed out more than ever here. She revered Rimbaud and Baudelaire, yet she also had shrewd instincts that served her well. She worked at Scribner's and later the Strand as a bookstore clerk for many years, and learned how to suss out good buys in collectors' editions. A move out of the Chelsea Hotel, where she and Robert lived for a year or two, and into a large studio space nearby, was financed by a 26-volume Henry James edition she found for cheap somewhere. Speaking of the Chelsea Hotel, that's the longest section in the book, with lots of interesting characters and obviously the period she remembers with the most fondness. She met Janis Joplin and William Burroughs there. She met Allen Ginsberg in an automat restaurant, where she was a dime short for what she wanted and he thought she was a boy he might be able to pick up. She had a kind of charmed existence for all its tribulations and difficulties then. Just Kids is perhaps most interesting of all for its story of the parallel developments of Smith and Mapplethorpe as artists. When they first met, thrown together two times by chance, he never intended to be a photographer and she never intended to be a rock star. They came to their places through one another, and not without their pains, because honestly, look how unlikely on the face of it that those two would end up together, given how far apart they went. Yet the bond was always there and always honored—that's the only thing to come away from this book with, and really it's a lot. It's the reason the book was written. It's very generous and in all the familiar ways Patti Smith is generous: acting the Earth Mother and the Holy Fool in the name of rock 'n' roll and art and poetry. It's a beautiful thing truly, and so is this book.

In case it's not at the library.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)